Charles Delmé-Radcliffe- in five Acts

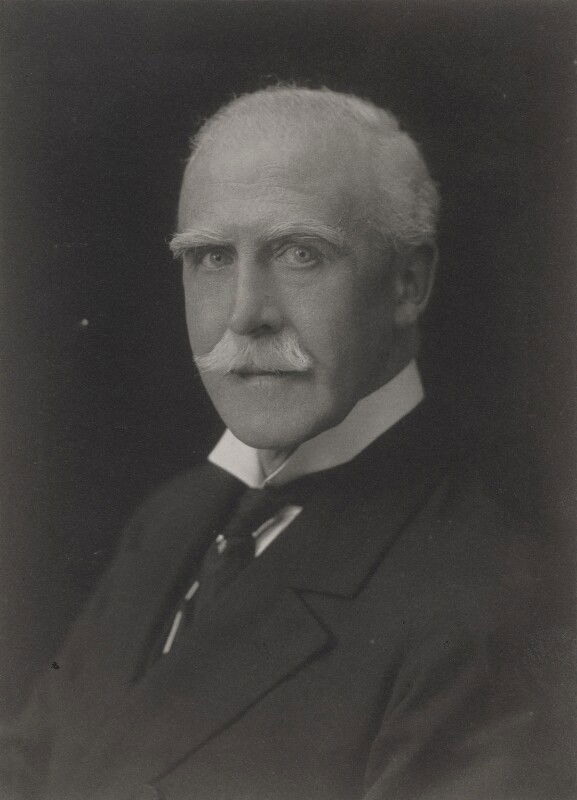

While I was researching William Howard Lister and Edward Brittani and the British Army in Italy in the Great War, one character kept cropping up ( beside the Prince of Wales). Brigadier-General Charles Delmé-Radcliffe.

Delmé- Radcliffe was in charge of British relief efforts when Lister joined the British Red Cross effort in Salonica during the 1912 Balkan War and later turned up as Head of the British Military Mission in Italy. There is a lot of information about Delmé Radcliffe out there, but nobody has ever dome a biography of him . He was a sort of Zelig like figure- turning up at key events. Mapping East Africa; observing the 1908 eruption of Vesuvius; leading relief efforts at the Messina earthquake in 1908; directing medical services in the Balkan war and finally taking tea with HG Wells, Rudyard Kipling and Conan Doyle on the Italian Front. He also took tea with Mussolini.- when Mussolini was still a friend and agent of the British. If one did three degrees of separation in early 20th Century Europe, I imagine most people at a certain level of power knew somebody, who knew Delmé-Radcliffe. By some accounts, he was not an easy person to deal with. Probably his wife thought that, she divorced him after he had left her behind for years on end, while he continued to go off on hi travels. As a military man , his career spanned from leading small punitive missions in Uganda to watching the industrial slaughter on the Italian front, for the rest he was also an explorer, geographer and observer.

Charles Delmé-Radcliffe was very much a product of his times, he went straight from a landed family with a military background to Sandhurst and then to India and Africa. His punitive raids in Africa might be regarded in a different light these days but he established a period of peace in that particular part of the world, albeit under British rule. Some of his comments about Italians particularly after the Messina earthquake would today have probably have got him fired had they leaked, but contextually he was writing in Confidential briefings for Ambassadors and never expected then to see the light of day. However a modern lens might see his earlier colonial career, undoubtedly, he made a major contribution to Anglo- Italian relations in the early 20th Century particularly his humanitarian work following the Messina earthquake and in the period before the British made a substantial military commitment to Italy . He seems an interesting footnote to history and worth exploring further.

Act One - Out of Africa

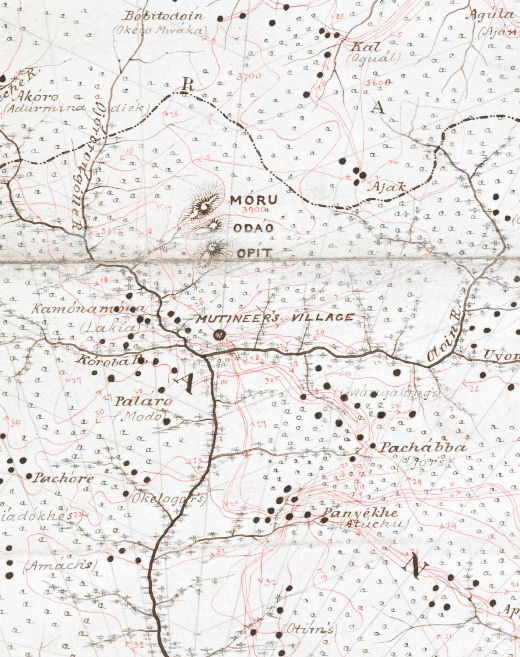

In 1898 Delmé-Radcliffe was attached to the Uganda Rifles(later to become the 4 K.A.R.), and in the same year participated in operations against Sudanese soldiers who had refused to undertake an exploratory expedition for the British and mutinied. The Sudanese Mutiny is one of those complicated and tricky bits of British Colonial history. The Sudanese had been loyally serving the British in Uganda and South Sudan ; however, they had apparently become disenchanted with long periods away from home and their poor pay and conditions. Three Sudanese companies were ordered to join the Juba expedition to explore the headwaters of the Nile ( the Sudanese did not know that this was part of a secret British plan to stop the French from reaching the Nile) Since the Sudanese were more worried about their clothing and pay , and less so with Anglo-French rivalry, -they mutinied and crossed to Bugoga where they took over a British fort and held hostage a number of Britons. A botched rescue attempt resulted in the British hostages being either executed or killed during the ensuing fight. The British bought in extra Indian troops and captured the mutineers' stronghold; however, a number of mutineers escaped and formed blood ties with the local Lango tribes. At which point that whole area descended into lawlessness. Delmé-Radcliffe arrived at Nimule in 1899 ( which is now in South Sudan or Darfur) and was appointed local Collector in charge of civil and military affairs. He spent the next few years trying to suppress the mutineers . During this time he became known to the locals as “Langa- Langa” ( Ghost or Were Lion) , due to his ability to get his troops to move silently through the night and turn up unexpectedly. Apparently another translation is something akin to “ bulldozer” – due to the destruction he left behind.

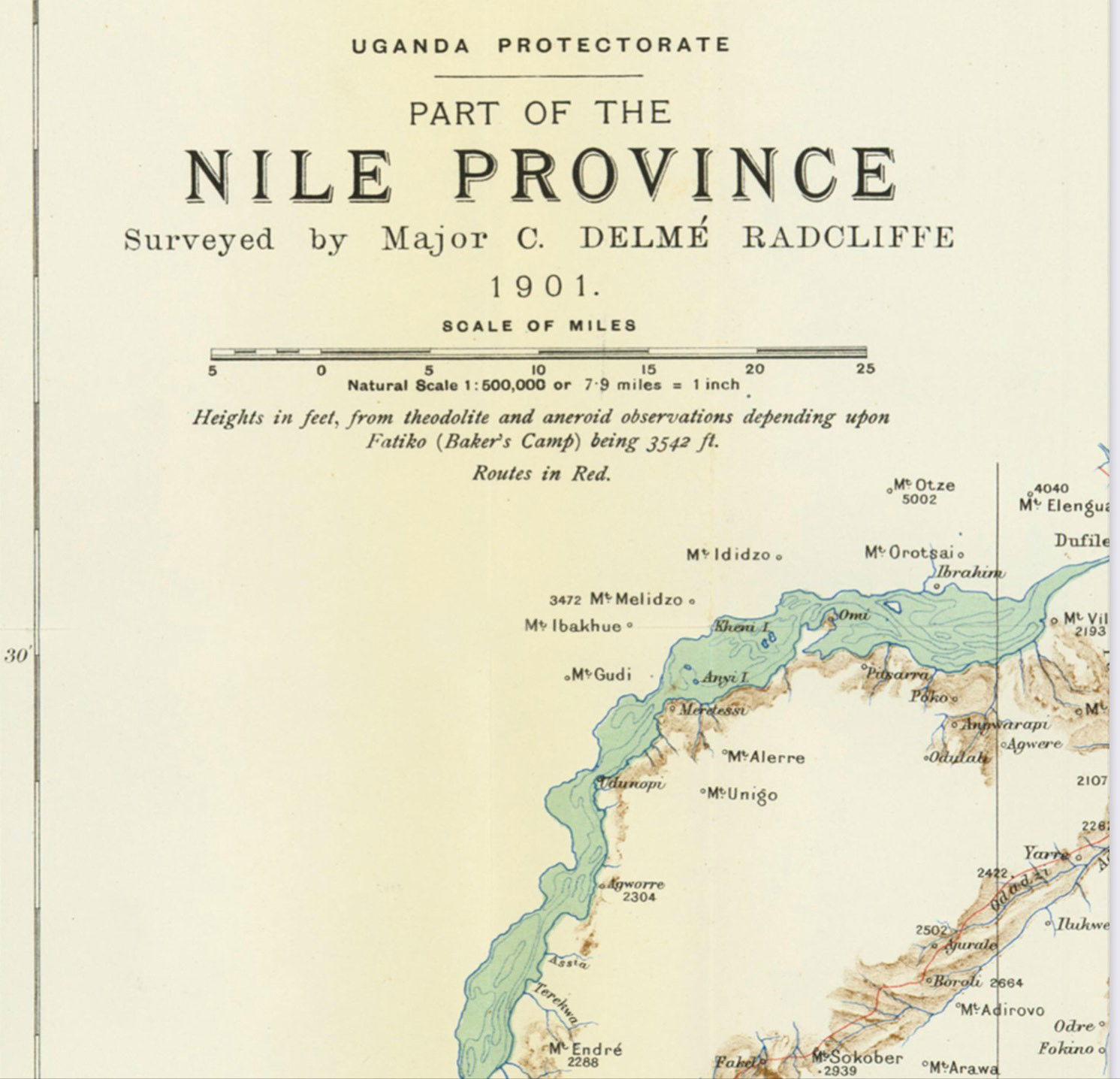

Apart from his punitive raids, Delmé-Radcliffe made a major contribution to the mapping of the area. Sir Harry Johnston, an old “ Africa hand” arrived in Uganda as Special Commissioner in 1899 to reorganise the administration of the area. One of the big problems he faced was the absence of any decent maps of the area. So he instructed Delmé-Radcliffe to conduct a thorough survey of the area. Fortunately he learned mapping and topographical skills from his time at the Army Staff College. Armed with a portable theodolite and sextant, Delmé-Radcliffe surveyed the area and becoming proficient in the local languages was able to add place names to the maps. He proved especially useful at mapping the exit of the White Nile from Lake Albert- Nyanza, which had not previously been done.

Delmé- Radcliffe's Map of Nile province

In 1901 Delmé-Radcliffe was appointed to the command of the Nile Military District with the role of eliminating the last of the Sudanese mutineers . He discovered through contacts with local chiefs that one of the last surviving groups of had holed up at Modo. From their headquarters the Mutineers, in conjunction with their Lango allies, carried out extensive raids, into the Acholi district. HQ provided him with a list of 103 Mutineers who were believed to be there, he offered them the chance to give themselves up, which only three accepted . So he set out with the Lango Field Force to neutralise the mutineers. The force comprised six Britons and 405 Native Officers, N.C.Os and Askaris from Uganda Rifles, plus a number of native levies. Delmé Radcliffe pursued a punishing programme of night patrols through dense forest and nine-foot-high elephant grass at the height of the rainy season. The river valley was flooded and the men often were wading neck deep in water. Many of them ended up sick with pneumonia, bronchitis and infections from cuts sustained on the papyrus. Still they marched on.

“The operations took nearly four months to complete. This slowness is in the main attributable to two causes. Firstly, the early commencement this year of a very heavy rainy season. Owing to this the grass even in May was everywhere very dense and varying in height, from 6 to 9 feet. The swamps were all full, and exceedingly difficult to cross. As they occurred every few miles and the grass covered the whole surface of the country, including the ground under the trees in the forest, it is unnecessary to insist further on the advantage this state of the country gave the enemy.”

The Lango Expedition

The mutineers were well supplied with arms and ammunition ( taken from the British) and with their military training, had established a well defended position. In his report of the operation Delmé-Radcliffe wrote:

"Their " station " was a collection of huts and houses covering a considerable area on an admirable site near the junction of the Oloin and Toshi Rivers. Many of the houses were rectangular and built in imitation of the European fashion. The whole was surrounded by a light palisade. A sentry-post on a high platform gave a good command of view over the whole surrounding country. A tall flag-staff was erected, no doubt to imitate still further an official station. The mutineers fought from the first, resisting the troops by every means,

The Lango Field Force attacked the mutineers at their stronghold in Modo and then sent flying out to round up any stragglers. . A total of 214 were killed and 1485 prisoners were taken by the Field Force, together with 10,000 cattle, goats and sheep, 3,000 spears and 88 firearms. Operations concluded with a specially devised de-oathing ceremony whereby the Lango tribesmen were injected by Delmé-Radcliffe's Medical Officer with a special emetic into the scar caused at the blood brotherhood ceremony. The resultant vomiting convinced the recipients that the evil spirit was departing.

Act Two - Under the Volcano- Vesuvius 1906

The Vesuvius Crater

Entry to the Vesuvius National Park

Having become an expert on East African borders, it was surprising although wholly in keeping with the idiosyncrasies of the British Army that in 1906 Delmé-Radcliffe was appointed as Military Attaché in Rome. It is not clear whether he had any knowledge of either Italian language or culture at the time, but he seems to have settled in quickly and rapidly became a confidant of the Italian King and military establishment.

When Delmé-Radcliffe arrived in Rome, at Embassy at the Porta Pia the British Ambassador was Sir Edwin Egerton, former Secretary of Legation at Buenos Aires; Consul-General in Egypt; Secretary of Embassy at Constantinople and Paris, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Greece and latterly Ambassador to Spain, During his time in Paris, Egerton was trained by Richard Lyons, 1st Viscount Lyons, who was then British Ambassador to France. Egerton was a member of the Tory-sympathetic 'Lyons School' of British diplomacy.

The old British embassy in Rome at Porta Pia

Italian King Vittorio Emmanuele III had acceded to the throne in July 1900, following the assassination of his father Umberto II by anarchist gunman. Vittorio Emmanuele was reticent and taciturn by nature.. He was also very short, which perhaps exacerbated his shyness and lack of self-assurance. He had been educated by an English nanny and an Irish governess who was the widow of a British Army Colonel. Apparently, he remembered speaking more English than Italian up until his fourteenth birthday. From that age his education had been entrusted to Colonel Osio, who introduced him to the classics , but was rather more successful in interesting his young charge in history, mathematics and numismatics. According to his mother, he never got past the first few pages of Manzoni’s I Promessi Sposi. Unpretentious and quite dull, Vittorio Emanuele did take a keen interest in military matters, eschewed a glittering royal life and lived simply. Apart from his passion for coin collecting, his main pastimes were fishing, shooting and photography. It is perhaps not surprising that the rather dull and unpretentious Italian monarch seems to have struck up a particularly warm rapport with Delmé Radcliffe.

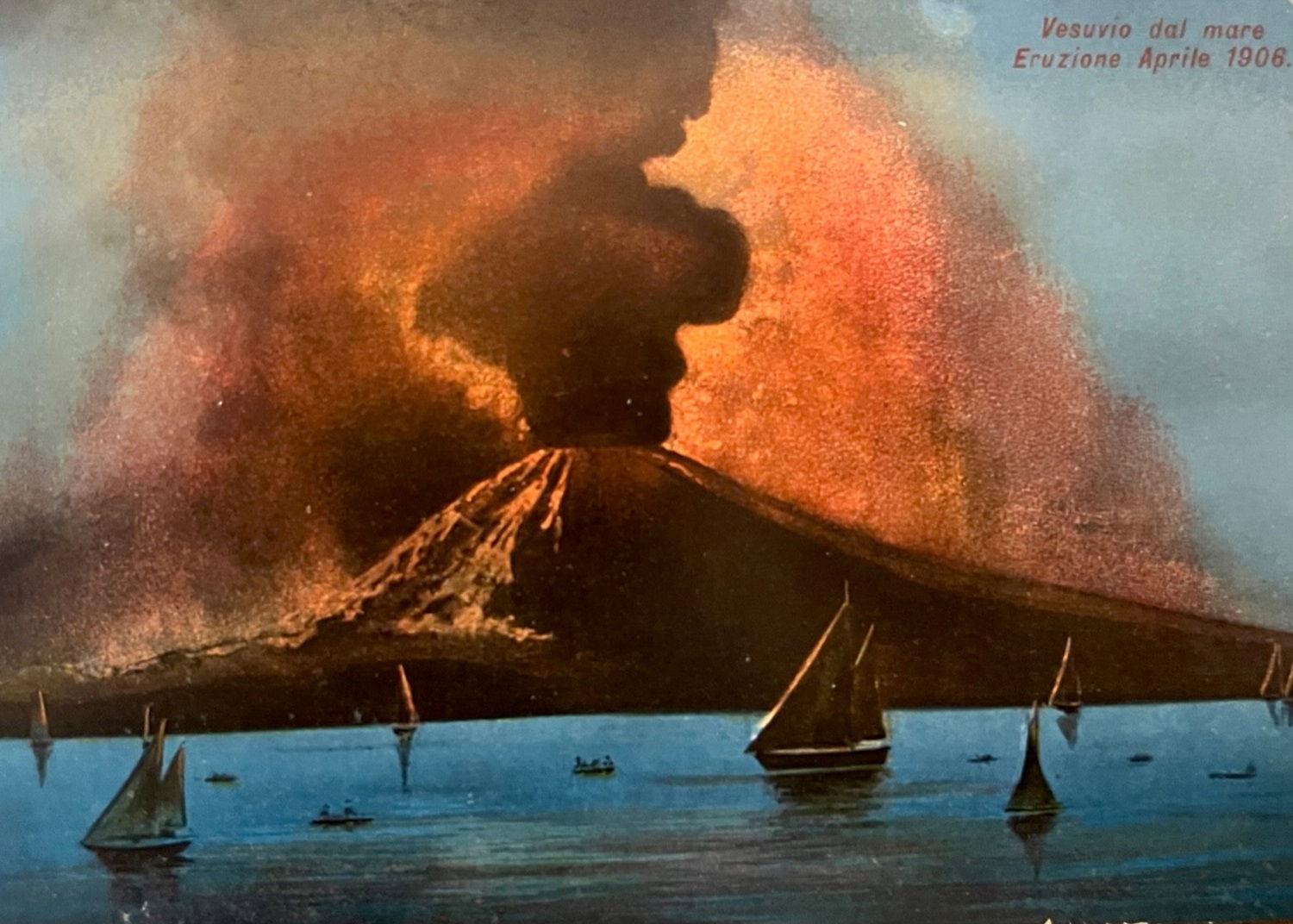

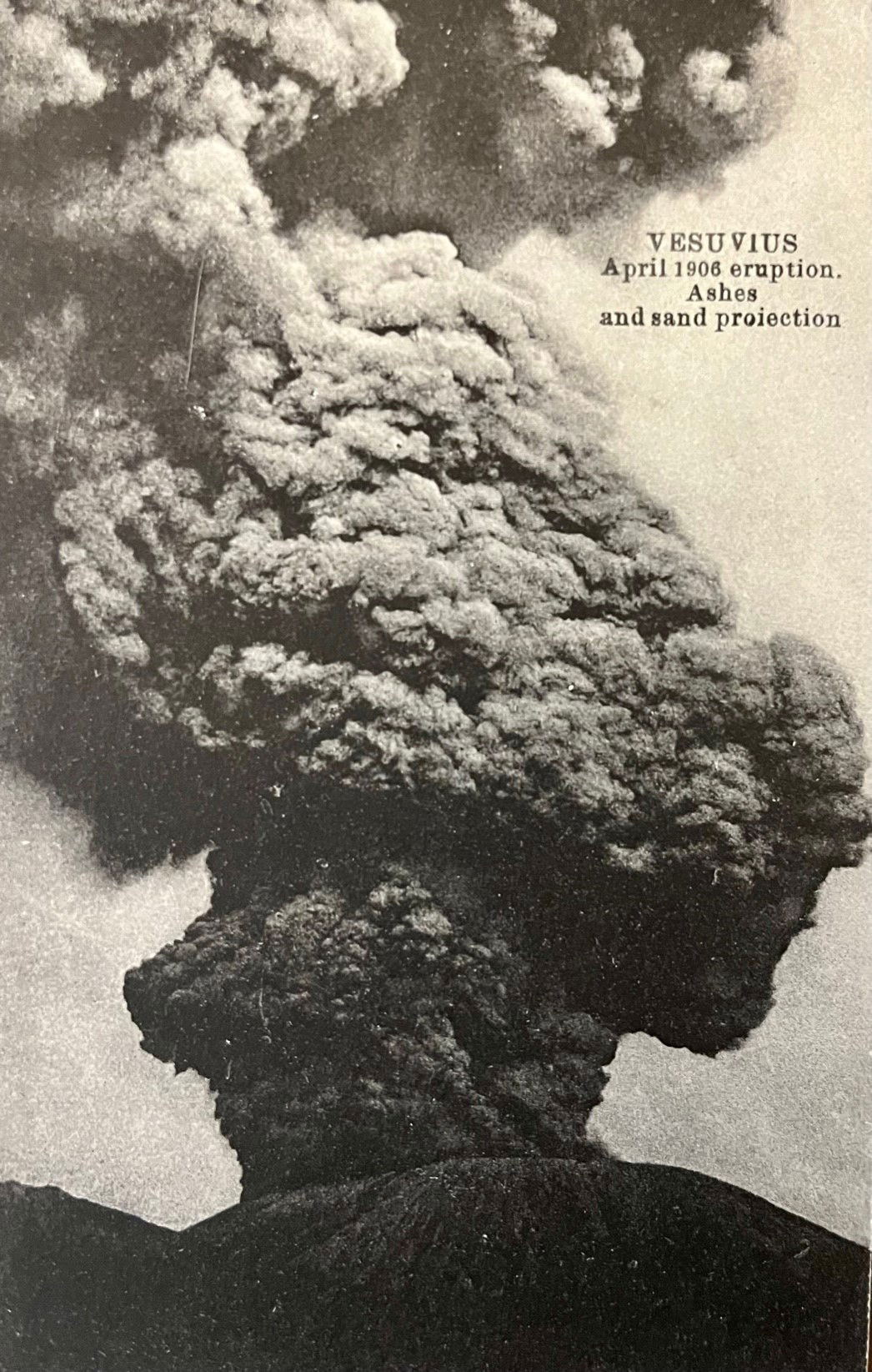

Delmé-Radcliffe was settling into Italian life , when Vesuvius erupted on 4 April 1906. Following a large sub-Plinian eruption in 1631, Vesuvius had been almost continually active , When discrete eruptions occurred these either involved lava flowing over the crater, or from fractures on the upper flanks of the mountain. Sometimes explosions and lava fountains accompanied these events. Episodes of repose, ranging from 2 to 6 years, interrupted the persistent activity.

The 1906 Vesuvius Eruption

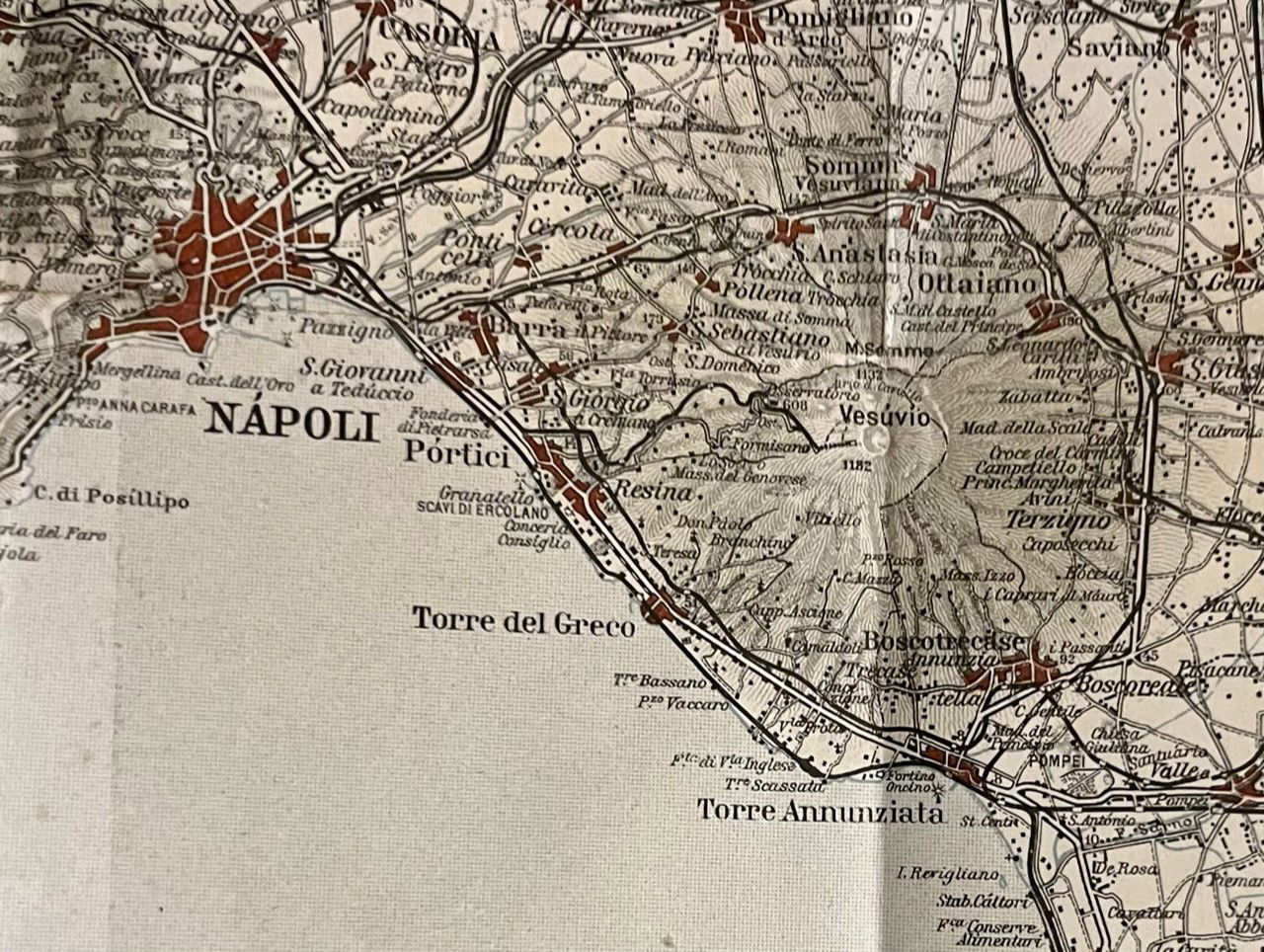

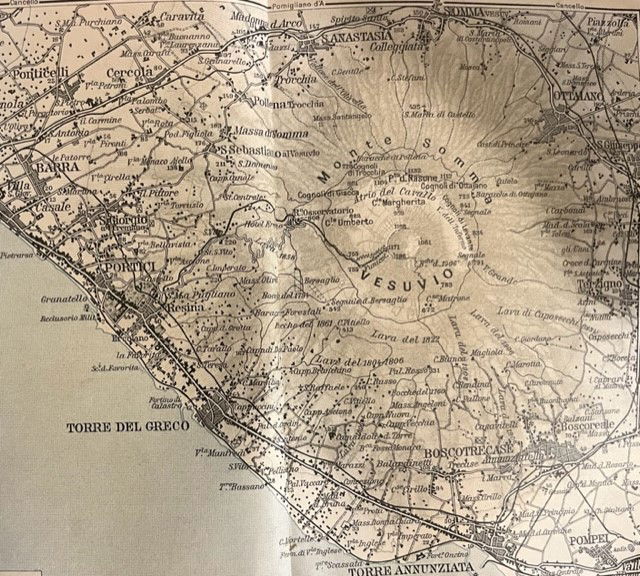

On 4,5 and 6 April lava flows erupted from several vents that opened at progressively lower altitudes on the south east flank of the volcano. Lava effusion was associated with moderate explosive activity at the summit and this waxed and waned every few hours. The longest lava flow was 5 km from the cone. On 7 April fire fountains reached a height of 3 km and lava destroyed part of Boscotrecase, with around 100 homes being destroyed in the suburb of Oratorio. Lava also entered the church of Santa Anna and eventually came to a halt on 10m from the cemetery at Torre Annunziata. The central crater was the site of explosive activity which increased in intensity early on 8 April . At 00.30 there were strong explosions and an earthquake, and at 02.30 a violent earthquake and emission of ash covered the north east sector of the volcano with a considerable quantity of tephra (both ash and lapilli). The villages of Ottajano (now named Ottaviano) and S. Giuseppe were badly affected and tephra reached a thickness of 1.25 m, causing several buildings to collapse including the church roof at Ottajano. After 03.30 - 04.00 h a sub-Plinian ash column was generated and during the afternoon reached a height of 13 km. This sub Plinian phase lasted 18 hours eroding the walls of the crater and eventually leading to the collapse of the summit cone.

The scene on 13 April 1906- as the ash and hot water mix

Between April 9-22, Large volumes of ash were erupted which fell on many settlements in the region including Naples, while heavy rainfall generated lahars causing extensive damage particularly in and around Ottajano. When the eruption ended, 216 people had been killed and 122 injured in S. Giuseppe and Ottajano and 11 killed and 30 injured in Naples. An estimated 20 x 106 m3 of lava was produced. Vesuvius was reduced in height by 115 m and the new crater was 700 m across and 600m deep. On 10 April, Delmé-Radcliffe left Rome to investigate the eruption and to report back to Sir Edwin Egerton.

“I left Rome by the night express on Tuesday, the 10th April. The journey was well up to time till within 6 miles of Naples. The cloud of smoke from the volcano was then being carried by a southerly breeze directly over Naples. When the train steamed into it, it became suddenly so dark that it was impossible to see one's hand in front of one's face, although a few minutes before we had been in bright sunshine. But this extreme blackness only lasted for about 2 miles. The train took two hours running the last 5 miles into Naples station. Naples itself was covered with a layer, 6 inches deep over everything, of very fine volcanic ash, impalpable as the finest fuller's earth and yellowish pink in colour. It covered everything like a layer of dirty snow, but had more tendency than snow has to cling to vertical surfaces. The effect was to make Naples silent and apparently deserted. All street sounds were subdued or muffled. The few cart-wheels made no sound; human voices had no reverberation, the few people in the streets went about in great-coats, with umbrellas up and goggles as a protection against the softly falling ash. It was as dark as in a bad yellow London fog. The whole was a strange contrast to the usual brightness and cheerful uproar of Naples.”

Once arrived in Naples, HM Consul General , Mr Neville Rolfe introduced his visitor to various Italian Generals at the Palazzo Salerno , explaining that his mission was to examine the Military arrangements that had been made to mitigate the disaster, he was given written authority to visit the cordon of troops around Vesuvius . While he waited to get to Vesuvius, some minor disturbances broke out in Naples , and the Cavalry rode in from Caserta to keep order, they created a favourable impression on Delmé-Radcliffe.

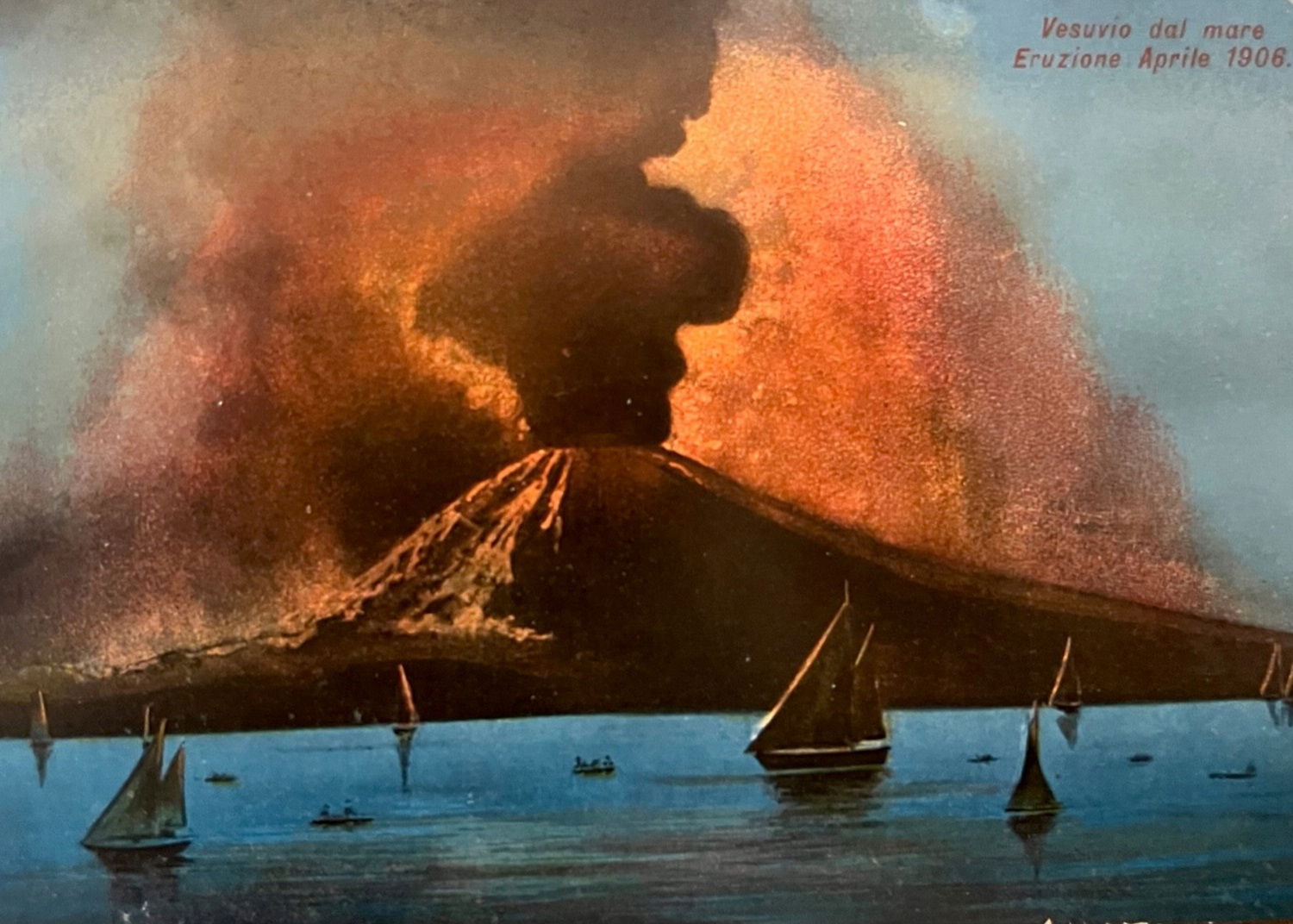

On 12 April, Delmé-Radcliffe managed to arrange a passage on a tugboat from Naples to Torre Annunziata on the coast below Vesuvius, accompanied by Neville Rolfe, As far as Torre del Greco, the boat steamed very slowly through dense clouds of volcanic ash , constantly sounding the foghorn to avoid collision. Torre del Greco “ loomed , deserted and ghost like , into sight – trees, houses, and everything the same pale grey colour”. From there things got clearer, and they were able to proceed in clear sunshine to Torre Annunziata. There he was taken to the HQ of Major General Confalonieri, the officer commanding , who sent an orderly officer to take him on a tour. The town remained undamaged and the only unusual thing that Delmé-Radcliffe observed was “a great cauliflower of smoke from Vesuvius rising 9,000 feet into the air”.

Vesuvius from Naples

Delmé- Radcliffe's inspection took him by boat from Naples to Torre del Greco and Torre Annunziata

Outside Torre Annunziata, he witnessed the edge of the lava stream, where it had stopped short just outside the town’s cemetery . He was then taken to Boscotrecase and Boscoreale , which were deserted and cordoned off by the troops who were having difficulty keeping looters out. His tour continued through Terzigno to San Giuseppe, although troops were trying to reopen the road the going was very difficult Delmé-Radcliffe note that the local people were not doing a great deal to help the troops . At San Giuseppe. There had been a disaster when the church roof fell in , killing 105 people who were sheltering inside. Having concluded his tour Delmé-Radcliffe returned to Naples or the evening.

The next day , he set off to visit the north and north eastern side of the volcano, in the company of Sr Hemsworth Williamson ( the High Sheriff of Durham) who happened ro be visiting at the time and Captain Holme of the Royal Engineers. They got as far as Somma Vesuviano by road , but from there the road became impassable They were able to proceed with the help of Major General Durelli, commanding the Engineers at Naples . whose troops had managed to clear the railway track to Ottajano – They found Ottajano to be totally devastated , with hardly a house intact . The troops were still at work digging in the vain hope of finding survivors . So far 90 bodies had been recovered there ; buy good fortune Just as they arrived an old man of eighty was dug out having been buried for five days.

His second tour - of the Northern side of Vesuvius to Somma Vesuviana and Ottajano

On Saturday 14 April , former British Prime Minister ( 1894-5) Lord Roseberry happened to be visiting the Bay of Naples in a large private yacht, so they sailed back to Torre Annunziata , where Roseberry wished to see the lave stream at Boscotrecase. Rosebery had purchased the Villa Delahente in Posillipo , just outside Naples in 1897, so presumably was visiting at the time. ( it is now renamed Villa Roseberry and is an official residence of the resident of Italy).

Delmé-Radcliffe was , of course , the Military Attaché rather than a disinterested scientific observer, so not unnaturally the last part of his report concentrates on the reaction of the Italian Military to the disaster. He is actually complementary concluding that.

“The eruption of Vesuvius has given occasion for military dispositions which afford an extremely interesting and suggestive study. It is clear that the staff work is extremely good, and it furnishes strong presumptive proof that a supply and commissariat organization that could respond so quickly and completely to this comparatively small , though unexpected demand would also be equal to the more serious calls of war”

He praised the work of ordinary Italian soldiers.

“The behaviour of the troops was altogether admirable. It is not easy to form an adequate idea of the conditions under which they worked – a suffocating cloud of volcanic dust, sometimes in complete darkness, no rest, the close and continue menace of the volcano, a panic – stricken and flying opulstion, destruction on all sides – and this going on for days together at some points. But the men stuck to their work, with patient pluck discipline, and a sympathetic consideration for the people worthy of ample recognition”.

He is also very complementary regarding the Italian Royal family.

“The example by the King and Queen of Italy and by the Duke and Duchess of Aosta[i] was inspiring to all. It is nothing , of course for men and soldiers like the King and the Duke of Aosta to go where the troops were working, but for the Queen and Duchess to have gone over and over again into the worst part of the afflicted area touched the people very much. The spectacle will not easily be forgotten of the Duchess of Aosta riding a troop horse on a trooper’s saddle, the only means of getting over the deep level of lapilli at San Giuseppe; or the Queen coming through the dark cloud of ash covered with mud from head to foot, owing to the hot rain precipitated by the volcano , to visit the ruins of Ottajano. “

Delmé-Radcliffe returned to Rome to write up his reports which he filed on 16 April 1906, Egerton subsequently forwarded it as an enclosure to the foreign secretary Sor Edward Grey. He continued his duties as Military Attaché and sometime confidant to the Italian King. Strangely his role also included being the part-time Military Attaché in Berne, Switzerland as a result of which he managed to write a book on Swiss Military conscription.

After the eruption Giollitti became Prime Minister once more. A strong economic performance and careful budget management led to a currency stability; helped by a mass emigration and remittances that Italian migrants sent to their relatives back home. The 1906–1909 triennium is remembered as the time when "the lira was premium on gold". Giollitti's government introduced laws to protect women and children employees with new time (12 hours) and age (12 years) limits. On this occasion the Socialist deputies voted in favour of the government, one of the few times in which a Marxist parliamentary group openly supported a "bourgeois government." The majority also approved special laws for disadvantaged regions of the Southern Italy. Such measures, although they could not even come close to bridging the north-south differences, gave appreciable results.

Act Three -" We learn geology the morning after the earthquake". Messina 1908

The City of Messina before the earthquake

Sir Edwin Egerton retired in December 1908 and was succeeded as Ambassador by Sir Rennell Rodd. When Egerton retired in 1908, The Times correspondent in Rome wrote:

“During his tenure of his post no questions of any great moment have arisen between the two countries but, should such questions arise in the future, Sir Edwin has simplified their solution for his successors by enhancing the kindly feeling of Anglo-Italian relations.”

Rodd had spent some of this earlier career in Rome and then returned between 1902 and 1904 as First Secretary of the Embassy. Such was his good reputation with the Italians from his previous tour, that he was apparently appointed Ambassador at the Italian Government’s and King's insistence. Rodd had hardly returned when Italy was struck by another and much more devastating natural disaster. In his memoirs Rodd recalls his return to Rome in December 1908.

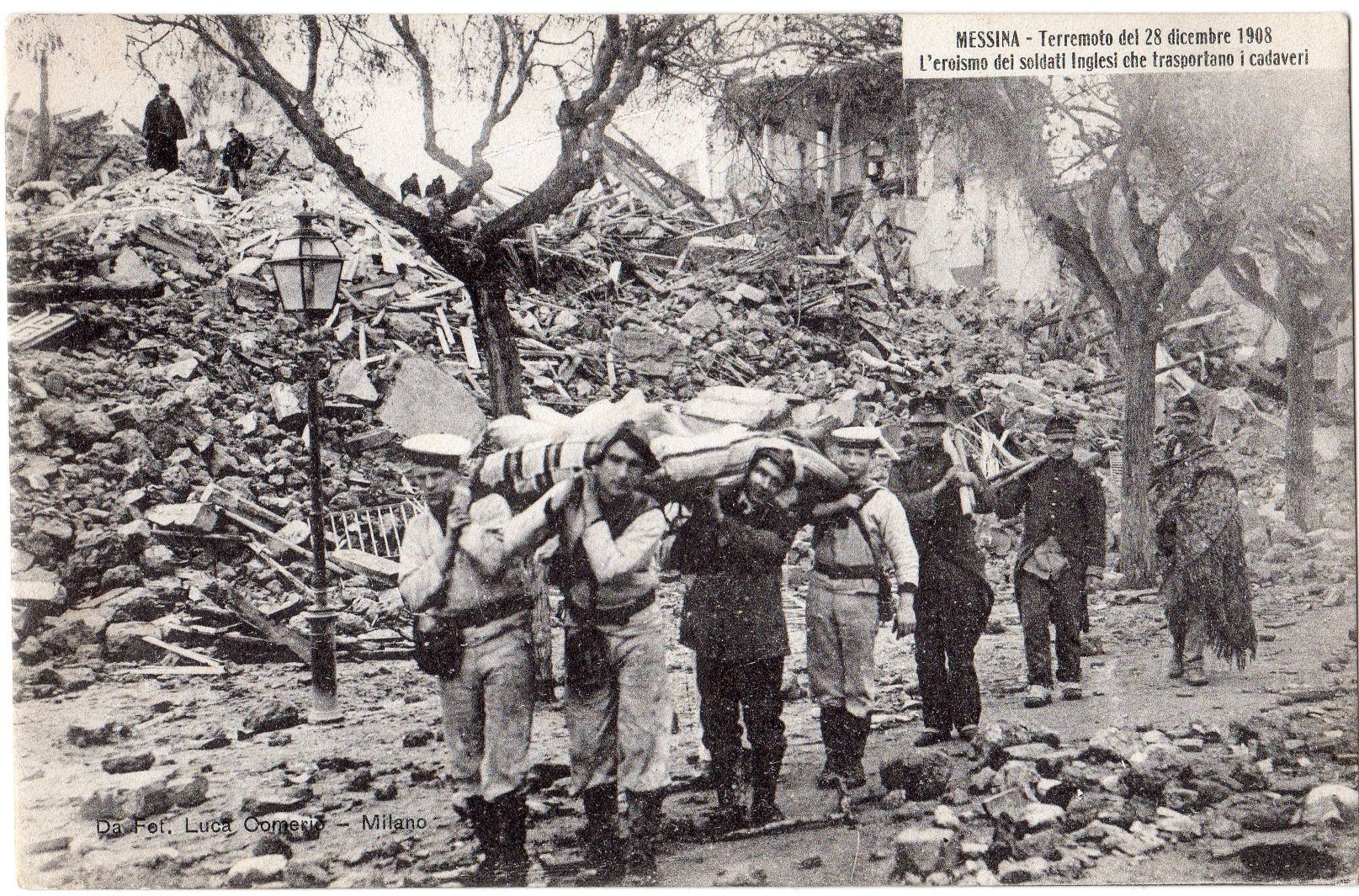

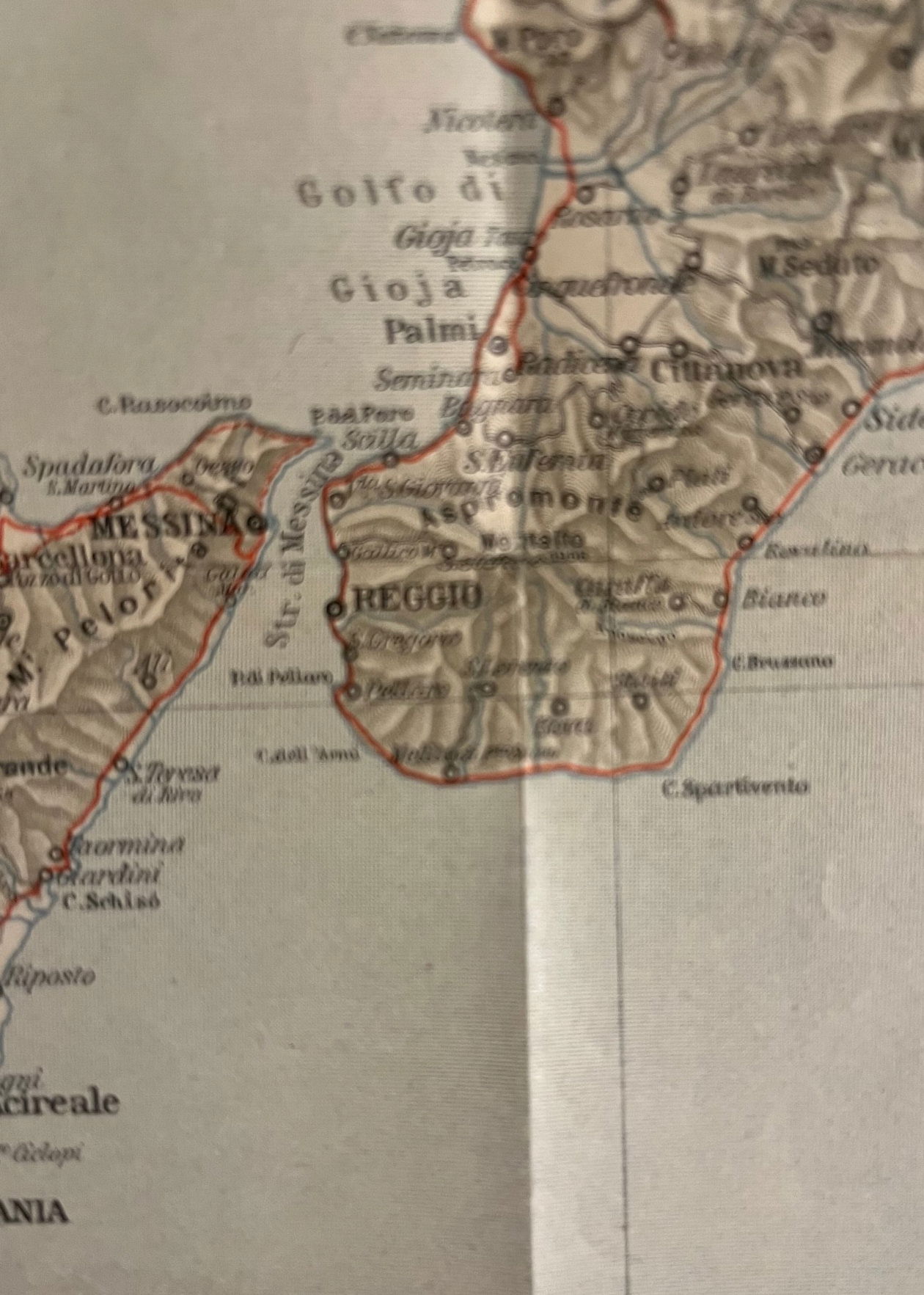

“We had hardly settled down in the Embassy at Rome when the appalling earthquake in the Straits of Messina took place. It devastated an extensive and populous area. But no shock was felt so far north as Rome. Owing to the interruption of all communications little accurate information reached us during the two days following the catastrophe. Then each successive message only served to intensify the magnitude of the disaster. Some two-thirds of the population of Messina was buried under the ruins, and at Reggio, on the opposite side of the Strait, the mortality was not much lower. Nearly all the troops in garrison at Messina were killed by the collapse of their barracks. The English chaplain and all his family perished. Our Vice-Consul and his child, though severely injured, were among the survivors, but his wife and their governess lost their lives. A sort of tidal wave raised by the earthquake invaded the ruins nearest the quays, and farther inshore fires broke out.”

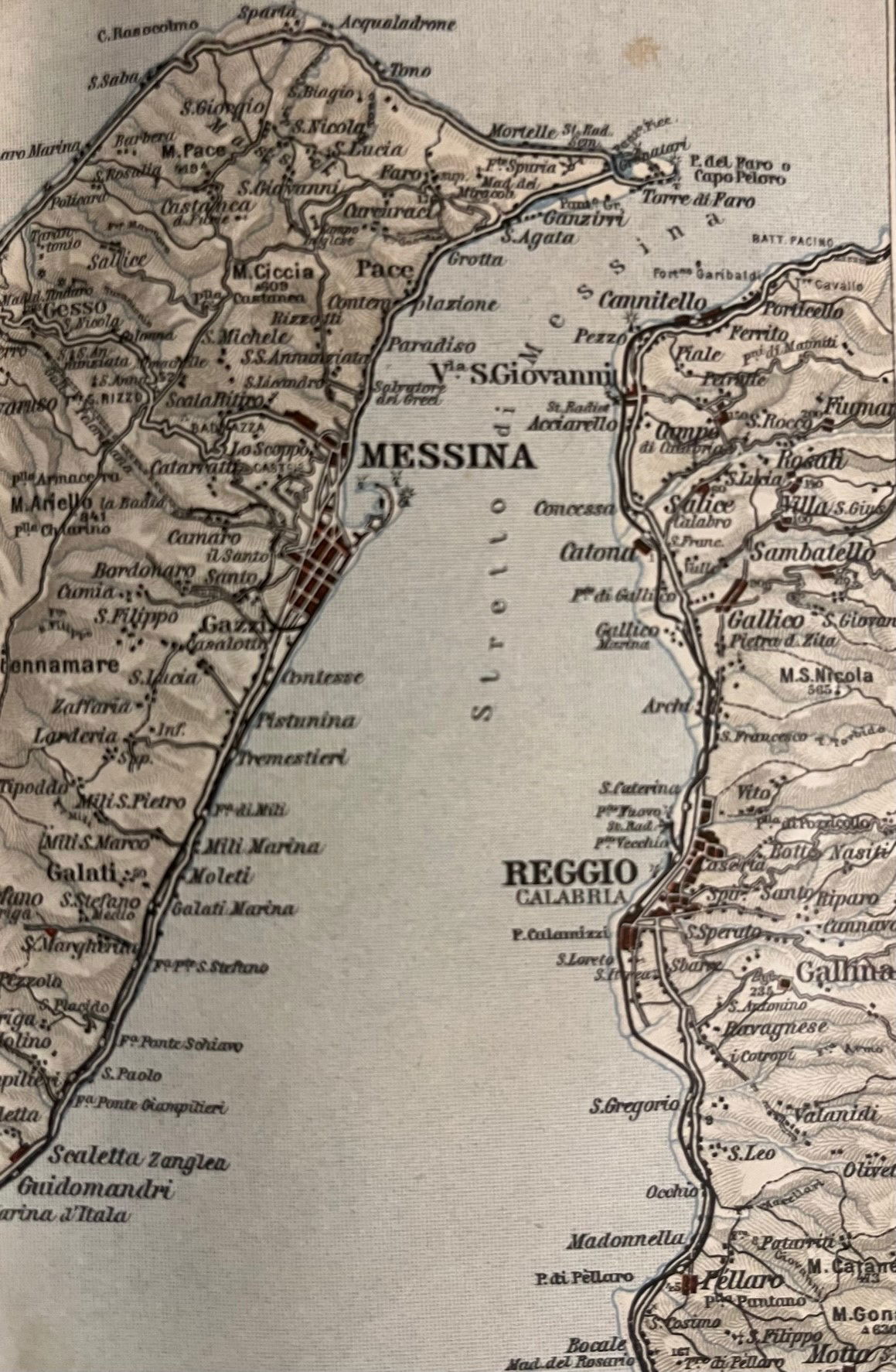

The Straits of Messina- epicentre of the earthquake

On 28 December 1908 Delmé-Radcliffe was dining at the house of one of the Italian King’s aides de camp , General Vittorio Trombi when they heard rumours that there had been a devastating earthquake in Messina . Trombi was an interesting character, who it was well worth Delmé Radcliffe’s while to cultivate. He was former Italian Military attaché in Constantinople, in which capacity he had managed to secure an introduction to observe British operations in the Sudan in 1896. After that he had cropped up as commander of Italian forces and effectively the civil governor of the Italian colony in Eritrea. He was next to be found, scoping out the port of Valona in Albania, in preparation for an Italian occupation. Although , perhaps it is no wholly accurate to describe him as a spy, Trombi was connected with Italian Military intelligence and with their shared African experience and interest in mapping strange places, he and Delmé -Radcliffe presumably had struck up a rapport.

Their convivial dinner was interrupted with the news that at around 5.20 that morning , a massive earthquake measuring around 7.1 had occurred with Its epicentre in the Strait of Messina separating the Messina in Sicily and Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland. The precise epicentre has been pinpointed to the northern Ionian Sea area close to the narrowest section of the Strait, the location of Messina at a depth of around 9 km (5.5 miles). The earthquake almost levelled Messina. At least 91% of structures were destroyed or irreparably damaged and some 75,000 people were killed in the city and suburbs. Reggio Calabria and other locations in Calabria also suffered heavy damage, with some 25,000 people killed and Reggio's historic centre almost completely razed. It was the most destructive earthquake ever to strike Europe, after Lisbon in ,,, The ground shook for some 30 seconds and the damage was widespread, with destruction felt over a 4,300 km2 (1,700 sq. mi) area. In Calabria, the ground shook violently from Scilla to south of Reggio provoking landslides inland in the Reggio area and along the sea-cliff from Scilla to Bagnara. In the Calabrian commune of Palmi on the Tyrrhenian coast, there was almost total devastation that left 600 dead. Damage was also inflicted along the eastern Sicilian coast, but outside of Messina, it was not as badly hit as Calabria.

Corso Garibaldi, Messina after the earthquake

About ten minutes after the earthquake, the sea on both sides of the Strait suddenly withdrew as a 12-meter (39-foot) tsunami swept in, and three waves struck nearby coasts. It impacted hardest along the Calabrian coast and inundated Reggio Calabria after the sea had receded 70 meters from the shore. The entire Reggio seafront was destroyed and numbers of people who had gathered there perished. Nearby Villa San Giovanni was also badly hit. Along the coast between Lazzaro and Pellaro, houses and a railway bridge were washed away. In Messina, the tsunami also caused more devastation and deaths; many of the survivors of the seismic activity had fled to the relative safety of the seafront to escape their collapsing houses. The second and third tsunami waves, coming in rapid succession and higher than the first, raced over the harbour, smashed boats docked at the pier, and broke parts of the sea wall. After engulfing the port and three city blocks inland beyond the harbour, the waves swept away people, a number of ships that had been anchored in the harbour, fishing boats and ferries, and inflicted further damage on the edifices within the zone which had remained standing after the shock.

The ships that were still attached to their moorings collided with one another but did not incur major damage. Messina harbour was filled with floating wreckage and the corpses of drowned people and animals. Towns and villages along the eastern coast of Sicily were assaulted by high waves causing deaths and damage to boats and property. Two hours later the tsunami struck Malta. In addition to the deaths caused by the earthquake, about 2,000 people were killed by the tsunami in Messina on the eastern coast of Sicily, and in Reggio Calabria and its coastal environs.] Records indicate that considerable seismic activity occurred in the areas around the Strait of Messina several months prior to 28 December; it increased in intensity beginning 1 November. On 10 December a 4 magnitude earthquake caused damage to a few buildings in Novara di Sicilia and Montalbano Elicona, both in the Messina. A total of 293 aftershocks took place between 28 December 1908 and 11 March 1909. In 2008 it was proposed that the concurrent tsunami was not generated by the earthquake, but rather by a large undersea landslide it triggered. The probable source of the tsunami was offshore of Giardini Naxos (40 km south of Messina) on the Sicilian coast where a large submarine landslide body with a headwall scarp was revealed on a Bathymetric map of the Ionian seafloor.

The following day Delmé- Radcliffe hurried down to the Palazzo Esercito in via Venti Settembre to see if he could find out any further information. There he was shown the text of telegrams received from Messina and informed that troops were being urgently sent from Rome and Naples to Messina and Calabria and that the King and Queen would be travelling don to Naples that afternoon. Delmé Radcliffe was given a letter of introduction to the Chief of General Staff in Naples, He had the time gather a few things together and then set off on the midnight train from Rome to Naples. Arriving n Naples the next day, it was still difficult to get any real information about what was happening further south. Delmé Radcliffe secured passage on the North German line steamer “Therapia” heading from Naples to Messina. As he entered the gates of Naples harbour , he witnessed large groups of wounded being carried up into the town, they had just been landed by the Russian ship "Makaroff” which had arrived from Messina. The Therapia had been in Messina that morning and had bought some 550 refugees to safety, among the was the nephew of the German Consul , who . Delmé Radcliffe questioned and then took to pass on the information to the Italian authorities. He persuaded the also roped in the Inspector of the North German Lloyd Company, Herr Manneking to accompany him to Messina in order to divert the German ship Bremen to help with relief works.

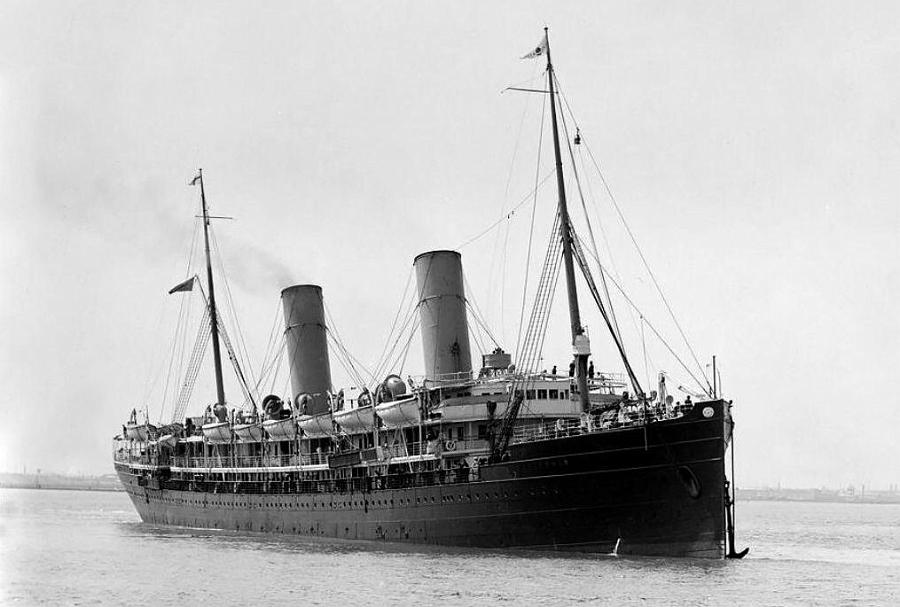

Therapia arrived at Messina early in the morning of 31 December and Delmé -Radcliffe went ashore at daybreak. After a brief inspection, his priority was to locate the British ship RMS “Orphir” which was on its way to the Straits of Messina, but which had no radio apparatus on board. The only way to find the Orphir was to borrow a torpedo boat from the Italians and head out to see to look for it. Delmé Radcliffe went on board the Italian flagship, Regina Elena to ask for help. On board the Regina Elena was the Italian Queen, who asked to see him. Delmé-Radcliffe found the Queen assisting Italian surgeons who were dressing the wounds in some of the survivors. The Queen updated Delmé Radcliffe on the full nature and extent of the disaster and requested him to go and help in Reggio Calabria. Still accompanied by the German , Herr Manneking he set sail for Reggio, where they went aboard the Italian battleship “Napoli” and spoke to Captain Umberto Cagni who made arrangements for the Orphir to anchor in Reggio. Finally , after dark Delmé Radcliffe managed to locate the Orphir and explain the situation to the captain who turned the ship towards Reggio. The Orphir loaded around a thousand refugees from Reggio, including around 300 badly injured in just under 4 hours and then sailed for Naples with them.

RMS Orphir- one of the British rescue vessels

Meanwhile Delmé-Radcliffe went back to stay on the “Napoli “and then New -Year’s Day went back ashore in Reggio with Captain Cagni to have a look around, before returning to Messina in a torpedo boat. At Messina , he went aboard HMS Sutlej to see if he could be of any help. He found the King of Italy on board and exchanged details about what he had witnessed that morning in Reggio, The King expressed his gratitude forelife work being done by the British squadrons at Messina and especially in Calabria. Fortunately, owing to their formidable Naval presence in Malta, the British were well placed to offer assistance. Having spoken to the King, Delmé Radcliffe set about reviewing and securing the records recovered from the British Consulate which has been completely destroyed by the earthquake. Delmé-Radcliffe was to remain on HMS Minerva as a base until 4 January Four British merchant ships were in Messina when disaster struck – the “Ebro”, “Chesapeake”,” Drake” and “Afonwen” . In his report Delmé Radcliffe remarks that:

“The officers and crews of these four ships appear to have done their duty as Englishmen from the first. The received large numbers of survivors- gave food and passage to other ports to many injured and refugees” .

The first foreign Naval vessels to arrive at Messina, were the British ships HMS Sutlej and HMs Boxer which had been at Syracuse just down the coast. Sutlej landed 400 men and a fire brigade at Messina, establishing a dressing station on the quay, which was able to treat hundreds of casualties Meanwhile, the newly appointed Field Marshal Commanding-in-Chief British Troops and High Commissioner in the Mediterranean, HRH Arthur Duke of Connaught offered tents, blankets stores and anything else that might be needed . Later that day HMS Minerva arrived and landed all available officers and men to search the ruins for survivors , establish a dressing station and to supply food and assistance to the injured.

More ruins in Messina. British sailors engaged in rescue and relief work

HMS Exmouth arrived on the morning of 31st December and took up station of the coast of Calabria to provide relief for the towns of Villa San Giovanni, Cannitello and Scilla. HMS Duncan, HMS Euryalus and HMS Philomel were sent from Malta to the Calabrian coast. They bought with them a Military Field Hospital with over 200 beds and 13 Nurses, together with a Military Bakery consisting of five field ovens sent by the Duke of Connaught. According to Delmé Radcliffe’s account, all the British ships had every available man ashore engaged in relief and rescue work . They landed immense quantities of stores and took over a thousand injured victims either to Syracuse or to other ships heading for Naples or Palermo. HMS Canopus and HMS Lancaster landed a large quantity of hospital stores for the British field hospital which had been established at Catona. On 11 January , HMS Aboukir arrived at Villa San Giovanni , with HRH , the Duke of Connaught on board.

The Duke assisted in landing some stores, and went to visit the Field Hospital at Catona, the next day he visited Messina and spent about an onshore inspecting the ruins of the city. Throughout the period , the officers and crew of the Orphir continued to provide valuable assistance with the relief work. While waiting to anchor , the crew had converted the second-class saloon into a temporary hospital , accommodating 180 mattresses and the ships doctor a well as a couple of doctors among the passengers set to work. According to Delmé-Radcliffe by the time the wounded began to come on board this part of the ship looked like a permanent hospital

To be fair, the British were not the only people providing assistance in Messina and Reggio and Delmé Radcliffe reports on the relief efforts of other nations. Three Russian ships arrived at Messina (Markaroff, Slava and Cesravich ). They were joined by a further two Russian gunboats , the Corietz and Giliack,. The Russians did admirable work both on land, and ferrying survivors to Naples. Also providing considerable support were French, German and even one Danish Naval vessel. Also, noteworthy, was the substantial American contribution to the international relief efforts.

Present in Messina at the time of the earthquake, were the Italian cruiser Piemonte, and several destroyers and torpedo boats. However , the tsunami which hit Messina after the earthquake had thrown many of the vessels against each other or the quay, severely damaging them. Captain Passino of the Piemonte had been ashore visiting his family in Messina and had been killed during the earthquake. In his absence Captains Cerbino and Ciano took charge of the Italian naval forces, Although the Piemonte managed to get her searchlights working to light up the ruins of the town, communications were difficult since the radio station at Fort Spuria had been destroyed. It was not until around an hour and half after the earthquake, that Cerbino and Ciano despatched one of the torpedo boats , Serpente north along the coast in search of a working telegraph . Serpente headed out of the devastated pot of Messina towards Villa San Giovanni , the found this to equally devastated, as were Scilla, Baggara and Palomi on the Calabria side all reduced to the ruins. Is was not until they got to the mouth of the river Metauro about 5 km up the coast hat the damage stated to lessen. Finally after about 5 hours sailing they reached Marina di Nicotera where they were able to telegraph Rome for assistance. Despite the fact that the telegraph was sent around 1 in the afternoon, it apparently did not reach the Ministry of Marine Rome until 5.25 pm that evening. At 5.55pm the Naval Commander in Chief was ordered to despatch the greatest number of ships possible for the relief of Messina. Between 6 pm and 7pm, the Italian Navy radio station at Monte Mario near Rome managed to get messages the Italian flying squadron, consisting of the Regina Elena, Vittorio Emmanuele and Napoli which at the time were sailing between Palermo and Sardinia, instructing the to turn around and head for Messina. By 9.15 further telegrams had reached Rome, setting out the total devastation at Messina, although the authorities remained unaware of the desperate situation o the Cabarian coast.

The Italians had to get as far as Nicotera - to fund a working telegraph station to notify the disaster to the world

Present in Messina at the time of the earthquake, were the Italian cruiser Piemonte, and several destroyers and torpedo boats. However , the tsunami which hit Messina after the earthquake had thrown many of the vessels against each other or the quay, severely damaging them. Captain Passino of the Piemonte had been ashore visiting his family in Messina and had been killed during the earthquake. In his absence Captains Cerbino and Ciano took charge of the Italian naval forces, Although the Piemonte managed to get her searchlights working to light up the ruins of the town, communications were difficult since the radio station at Fort Spuria had been destroyed. It was not until around an hour and half after the earthquake, that Cerbino and Ciano despatched one of the torpedo boats , Serpente north along the coast in search of a working telegraph . Serpente headed out of the devastated pot of Messina towards Villa San Giovanni , they found this to be equally devastated, as were Scilla, Bagnara and Palomi on the Calabria side all reduced to the ruins. Is was not until they got to the mouth of the river Metauro about 5 km up the coast hat the damage stated to lessen. Finally after about 5 hours sailing they reached Marina di Nicotera where they were able to telegraph Rome for assistance. Despite the fact that the telegraph was sent around 1 in the afternoon, it apparently did not reach the Ministry of Marine Rome until 5.25 pm that evening. At 5.55pm the Naval Commander in Chief was ordered to despatch the greatest number of ships possible for the relief of Messina. Between 6 pm and 7pm, the Italian Navy radio station at Monte Mario near Rome managed to get messages the Italian flying squadron, consisting of the Regina Elena, Vittorio Emmanuele and Napoli which at the time were sailing between Palermo and Sardinia, instructing the to turn around and head for Messina. By 9.15 further telegrams had reached Rome, setting out the total devastation at Messina, although the authorities remained unaware of the desperate situation o the Calabrian coast.

Delmé -Radcliffe remained at GeneraI Mazza's headquarters until 25 January and made trips to Catona, Catania, Taormina, and Calabria to organize Committees and arrange for the distribution of relief in under instructions from His Britannic Majesty's Ambassador in collaboration with the military authorities and the Italian Relief Committees. He returned to Rome on the 27th January and started writing up his report.

In his general concluding remarks , Delmé -Radcliffe makes a series of rather strong conclusions about the performance of all concerned.

Other Military Attachés - , he gives credit only to those of the United States, who stayed through to the end. The German Military Attaché committed the indiscretion of complaining about the food and accommodation and of not being given special quarters for his valet. This only added to the bad feeling the Germans had caused after Vesuvius.

The Italian Army - although, he is generally in favour of the Italian Army , Delmé Radcliffe was still fairly damning:

. “The officers and non-commissioned officers have not much authority. They cannot command quietly and yet authoritatively, so as to get the best and most willing services. They either nag at and worry the men, or they are foolishly weak and paternally overindulgent”

Of the Italian officers only Captain Cagni comes out well, as a fellow explorer and man of decisive action

. “Very few of the senior officers ever acted on their own initiative with energy and decision. But a striking exception to the rule was Captain Cagni, of the "Napoli", ....Captain Cagni is one of the officers who accompanied the Duke of Abruzzi on some of his exploring trips. It may well be that the unconventionality of, and the experience gained on, those expeditions, developed the breadth of view and decision of character which enabled him to achieve something tangible and good, when almost all the other officers, individually, did very little.

Italian Soldiers engaged in relief operations

The Italian authorities- in his view the Italians were both jealous of and failed to correctly use the considerable foreign aid that was given to them:

“In addition to failing to do things for themselves the Italian authorities, at first, were exceedingly jealous of anybody else doing anything. If the naval commanders had had their way, it is probable that not a single foreign ship would have been allowed to rescue a souI. The grave statement must be made that they were willing to allow thousands of their own people to die in the most dreadful suffering, sooner than to allow it to appear that they themselves were not capable of fully dealing with the situation.”

In view of the conflict to come, there were certainly some lessons to be leaned

“The attitude of the authorities and the disposition of the Italian people Iead one to think that in the event of the necessity for working with Italian military or naval forces as allies, the support of the Italian Commanders might not be much more reliable than that of the Spanish Generals in the Peninsular war.

The Royal Family - Delmé Radcliffe was particularly close to the Italian Royal Family and is most complimentary about them;

“It was indeed fortunate in many ways that His Majesty appeared so promptly on the scene of the disaster. His arrival and that of the Queen acted like magic in infusing energy and vitality into the authorities and to encouraging the population. But for the direction and example of His Majesty the arrangements would have been far less efficacious than they were. "

The Italian Population in general - he is less complimentary about the rest of the Italian population:

“The apathy and indifference of the Italians to the sufferings of their own people, - the apparent incapiy to realise the sufferings of others – were a curious and unexpected phenomenon. There is much easily aroused sentimentality in the Italian nation, and it is difficult to reconcile the extravagant language and excited veering of one moment with the strange callousness of the next, as all being phases of the same character.

Medical services

“The Italian medical services contain many very capable surgeons and theorists on medical science, but, in practice, as seen at the earthquake, the results achieved by the Army Medical Staff couId hardIy have been more disappointing”

Public officials

“The great majority of the communal authorities, the Syndics and Prefects, were utterly untrustworthy. Consequently, funds could not be placed in their hands and frequent cases occurred of their converting to their own use, stores intended for the relief of sufferers. This universal dishonesty of the civil authorities is an immense handicap to Italy and in time of war would constitute a national peril”

Communications “The wireless apparatus of the Italian men-of-war worked with most disappointing lack of efficiency considering that it is Marconi's native country. It was extremely difficult for the authorities themselves to obtain information from anywhere and communications between Rome, Naples, and Messina were very precarious”

Writing on 22 April 1909, Delmé Radcliffe signed off with a characteristic blast at the apparent lack of any concrete progress

“Hardly any practical steps have yet been taken to restore normal conditions. Ineptitude, dishonesty, opportunism, are the characteristics of the civil authorities. FiIth, misery, and the absence of any material regeneration prevail in the country afflicted by the earthquake, and will probably do so for a long time to come.”

Act Four - A Balkan Interlude

The First Balkan War began on 8 October 1912, when the Balkan League member states ( Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, and Serbia) attacked the Ottoman Empire. Apart from the grave threat to regional peace and the fact that the Great Powers might be sucked into the conflict, there was also the humanitarian concern that having started a war, the Balkan States were helplessly insufficient in medical resources to deal with the military casualties and refugees likely to result. The Crown Princess of Greece (Princess Sophia) appealed to Queen Alexandra ( the late Edward VII’s consort) asking whether she could help with the sick and wounded. Queen Alexandra passed the request to the British Red Cross who decided to send out medical teams.

On the outbreak of hostilities, the Council of the British Red Cross Society, at a special meeting, agreed to send medical assistance to each of the belligerents, and placed the arrangement of details in the hands of the Executive Committee. As the invested funds of the Society were only available for wars in which British troops were engaged, an appeal for subscriptions was made in the press, and a generous response was the result. The British Red Cross Balkans Fund received donations of £41,000 in the first few days and while support dipped a bit after that, wealthy private individuals made up the difference. The Medical Relief committee was thus able to fund three separate British medical units – one for the Balkans, one for Greece and the last for Turkey. In London, the Chairman of the Red Cross Medical Relief committee was the eminent doctor and veteran of the South African War, Sir Frederick Treves ( who happened to be Delmé-Radcliffe’s father-in law )Setting up offices in Westminster Sir Frederick busied himself with recruiting the necessary medical staff, soon the offices were one of the busiest places in London dealing with applications from established doctors and young medical students who wanted to do their bit. The Governments of all the belligerents gratefully accepted the offer of the British Red Cross Society (made on October 8) to dispatch assistance, and the Foreign Office sanctioned the proposal. The Society appointed three "Red Cross Directors" to supervise the work of the parties it was proposed to send to the seat of. war., Surgeon-General G. D. Bourke, C.B., for Bulgaria, Servia, and Montenegro; Colonel C. Delmé-Radcliffe, C.V.O., C.B., C.M.G., for Greece; and Major C. Doughty-Wylie, C.M.G:, for Turkey. The first party set out for Montenegro and on 27 October 27.the party under Delmé-Radcliffe,; and Major Roughton, R.A.M.C., the Senior Medical Officer, set out for Greece. In addition to the equipment (personal, ordnance and medical), this party took out a large quantity of food of .various descriptions, and miscellaneous stores, of the value of about £500.Thety took the train across Europe to pick up a ship in the Adriatic En route the baggage was detained temporarily at Salzburg, owing to the blunder of a station-master. So the "units" arrived at Trieste, and embarked on board the Austrian Lloyd boat, without their equipment. A medical officer and an orderly had to be left behind to bring it on by the next steamer. Two days subsequent to the arrival of the "units" in Athens (on November 4) application was made by the authorities that the entire party should embark in the hospital ship "Albania" and proceed forthwith to Volo in the neighbourhood of Salonika, then closely besieged. . With the greatest difficulty, and at an exorbitant cost, certain necessary surgical and medical stores were procured locally.

On the Macedonian front, the war unfolded rather rapidly. Ottoman intelligence had also disastrously misread Greek military intentions apparently believing that the Greek attack would be split between: Macedonia and Epirus, so the Ottomans divided their forces accordingly. The Greeks army concentrated all its strength against Macedonia, and In an unexpectedly brilliant and rapid campaign, seized Salonika. When The Ottoman commander, Hasan Tahsin Pasha, surrendered Thessaloniki and its garrison of 26,000 men to the Greeks on 9 November 1912.

The Greek Army enters Salonica in November 1912

The British Medical mission was then able to enter the city. On 10 November the medical officer left behind arrived there with the original equipment, and a hospital was allotted to the British Red Cross. The British unit occupied the Turkish Municipal Hospital, which although well-designed , was defective in its sanitary arrangements. The hospital could hold 250 patients, but ended up with more than 585 sick and wounded crowded in the building. Sick and wounded were placed in the corridors, landings and wall spaces they arrived at the hospital without warning at any hour of the day or night and often in very bad condition .

In one report , Delmé Radcliffe reported that since they opened the hospital:

" they have been working all day and night, and all sleep on the stone floors." Eight hundred sick and wounded have just been transferred by steamer to Athens. Major Houghton and a lightly equipped party are (November 18) on their way to Vodena where a battle is expected to take place between that town and Monastir. A rest camp is being formed for all those patients who are suffering only from starvation and exhaustion, so as to relieve the greatly overcrowded hospital.”

He added

"The whole party are as good a lot as one could wish for, and they are earning golden opinions. There is a vast amount of destitution and suffering among the thousands of refugees, who have crowded into the city, a condition of things which the Society is doing its utmost to combat”.

Act Five - The Italian Job- Princes, authors and intelligence

Fortunately the First Balkan War was over fairly quickly and Delmé- Radcliffe returned to semi- retirement. When Italy entered the war on the Allied side in 1915 , with his existing contacts in and experience of Italy , Delmé Radcliffe was sensibly appointed , Chief of the British Military Mission attached to the G.H.Q. of the Italian Army at Udine. ( Presumably no Italians had ever been privy to the contents of his Messina report). Quite what the British Military Mission did is somewhat mysterious , apart from maintaining an entirely separate chain of communication between the British General Command and the Italian Commando.. This does seem to have become a source of tension with the Ambassador, who was still Sir Renell Rodd. He described the Mission in the following terms

“ I received through the Foreign Office , a memorandum drawn up by the War Office, defining the functions of the Military mission and the correlative position of the Military Attaché. Its terms seemed quite satisfactory, and f property observed they should have ensured general co-ordination with the embassy at Rome. Unfortunately during the war there seems to have been a disposition in departments at home to shut themselves up like watertight compartments, and not always to remember that in a national cause all were members one of the other. This disposition was to a certain extent represented in their agents abroad. It is perhaps unnecessary to elaborate this point further, but I cannot do otherwise than insist that a tendency , which was , I gather , not peculiar to my experience , on the part of the Military Missions to act rather in rivalry and competition that in co-operation with the diplomatic establishment was much to be regretted , not only on the grounds of expediency but on account of the impression it produced in the country where they were stationed “.

Sir James Rennell Rood, British Ambassador at Rome - his relations with Delmé Radcliffe were not particularly harmonious

Clearly with the King at the front , and only a Regent remaining in Rome and also with the presence of General Cadorna at the front , Delmé Radcliffe up in Udine had better access to the senior Italian figures than the Embassy in Rome. The inference is that Delmé-Radcliffe indulged in a bit of Empire building up in the North and that his direct communication to the War Office and General Staff in London, were cutting out the Rome Embassy Occasionally they worked together. When the British Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith visited Rome in March 1916, Delmé Radcliffe seems to have come down to the ternal city for the occasion, since it was reported that he accompanied the British Party on the train from Rome to Udine and then facilitated their visits to the King, Cadorna and the frontlines.

As well as submitting copious reports back to Britain, Delmé -Radcliffe also seems to have had a propaganda function. Although British Guns and troops would later arrive on the Italian Front ( after the debacle of Caporetto) . between 1915 and 1917, Delmé Radcliffe’s role was confined to liaison and largely public relations.

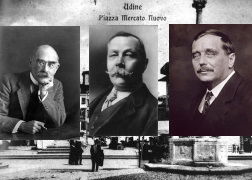

After the Italians entered the war, the British made a considerable effort to interest the public at home in the Italian Front, and Delmé- Redcliffe and his Military Mission played host to a variety of politicians and, British authors and journalists keen to visit the Italian Front and write about their experiences on the Italian Front. The author visits seem yo have been one of Rodd's initiatives, From the white villa in Udine, which housed the British Military Mission, Delmé- Radcliffe proved to be genial and well- informed host and with his impeccable connections was able to secure introductions and interviews with both the King and senior Military figures. In June 1916, Arthur Conan Doyle arrived at Udine to be met by Delmé Radcliffe who he described as “ a bluff, short-spoken and masterful British soldier”. Conan Doyle was accommodated by the British Mission at a White House on the outskirts of Udine, where he found a long dark smear on the white washed wall beneath his bedroom window, it was in fact the remains o an Italian blown up by an Austrian bomb which had landed outside, Delmé- Radcliffe arranged for Conan Doyle to visit the Isonzo Front, Monfalcone, the Carnic Alps and Trentino. Conan-Doyle wrote about his experiences in the book , “A Visit to Three Fronts” published in 1916, where the chapter “A Glimpse of the Italian Army” records his generally favourable view. He later published a similar chapter in his book “Memories and Adventures”.

A literary trio on the Italian Front. Rudyard Kipling; Arthur Conan Doyle and HG Wells

In August 1916, it was the turn of HG Wells to visit. Again Delmé-Radcliffe facilitated the arrangements. Wells was accommodated in the same room at the British Military Mission as Doyle ( “ there were holes in the later ceiling and wall....holes that had been caused by a bomb that had burst and killed several people in the little square outside! . “) From Udine Wells was taken out to the surrounding areas on the Isonzo front to the Carso and San Martino. Radcliffe arranged a trip out to the villa near Udine for an interview with the King. Wells wrote about all this in several chapters of his book “War and the Future” ( 1917)-The last distinguished literary visitor was in May 1917, when Rudyard Kipling arrived to visit the front ,R again fixed with Kipling to meet the King and Cadorna, arranged for a car trip out towards the frontline at Gradisca. It was not just authors, Delmé Radcliffe also assisted with the arrangements for press baron, Lord Nothcliffe’s visit to the Italian Front, in his book Northcliffe records his thanks to

“Brigadier General Delmé Radcliffe , head of the British military mission at Italian Headquarters, whose acquaintance with military Italy is probably unique and who seems able to dispense with sleep and is at his desk or in the field 18 hours daily”

With distinguished literary visitors gone, Delmé Radcliffe settled back to sending updates back to London on the situation in Italy. These got rather more urgent and frequent when the Italian Font collapsed at Caporetto in October 1917. Delmé Radcliffe stayed in Udine until he city was abandoned by the Italians and all the military missions moved down to the Padova area. Following Caporetto, the British sent troops to Italy and with the arrival in Italy of Generals Plumer and Cavan, with their entire staffs , when General Cavan and later General Plumer arrived in Padua , Delmé Radcliffe was able to brief them on the position on the Italian Front. With new British Generals in Italy his influence over the Italians presumably waned a bit. Nevertheless , he kept his Italian contact list and even added some new ones. In March 1918, he encountered Benito Mussolini, by this time a fervent interventionist, who gave him a resume of the Italian political situation and urged the British to use their influence to ensure that the Italian troops were paid more and that there was a crackdown on defeatist elements. .Delmé Radcliffe apparently described Mussolini as “a most interesting and able man”

It appears that Delmé Radcliffe was not particularly popular in certain quarters, a journalist reported.

“Wherever he has been he has acquired an abiding unpopularity I know that many soldiers of position at home and elsewhere are thankful that he has been “shunted “ to Italy....He goes beyond his duty as our representative and suggests that he really is God Almighty and Sir Douglas Haig rolled into one tremendous personality,. He is a man of tremendous and boundless energy but of limited intelligence . He is an arriviste and has not known how to disguise it. “

After the defeat of Austria Hungary , Delmé Radcliffe left Italy and ended up leading a British Military Mission in the occupied Austrian city of Klagenfurt,

[i] The Duke of Aosta, was the King of Italy’s cousin. He was born in Genoa the eldest son of Prince Amadeo of Savoy, Duke of Aosta and his first wife Donna Maria Vittoria dal Pozzo della Cisterna. In 1870 his father was elected to occupy the Spanish Throne. Amadeus resigned and returned to Italy in 1873 after three years on the throne. Emanuele Filiberto joined the Regia Esercito in 1884 and entered the Military Academt in Turin. . In 1890 he succeeded to the title of Duke of Aosta. In 1906, he was appointed to command the Army Corps based at Naples and moved his whole family to the Capodimonte Palace, in the hills above Naples. The Duchess was formerly, Princess Hélène of Orléans (French: Princesse Hélène Louise Henriette d'Orléans; 13 June 1871 in York House, Twickenham – 21 January 1951 in Castellammare di Stabia, Italy) was a member of the deposed Orléans royal family of France and, by marriage to the head of a cadet branch of the Italian royal family, the Duchess of Aosta.