David Roberts- Milan April 1945

The ordeal begins

If you had to put a start date for Milan’s long ordeal, 12.20 on 13 May 1943 would be a good one. At that time , Italian General Giovanni Messe gave the orders to all Axis forces in clinging to a toehold in Tunisia to surrender to the Allies. The Allied Victory in Tunisia secured the vital staging point from which they could launch an attack on Italy; Churchill’s “soft under belly of Europe”. On 10 July, Allied forces landed in Sicily. Up until then Milan had been a long way from any front-line. Yes it had been visited by RAF bombers on odd occasions, but was left largely undisturbed. Milan's industrial and engineering business remain largely undisturbed and continued to produce. Despite the privations of war, life continued much as normal. In May 1943, Milan has suffered substantially less from the war, than say Paris, Brussels and many occupied capitals, less than London and less than many German cities which were nightly being laid waste by the Allies. Life was not good but it continued.

All this changed with the surrender in Tunisia and the landings in Sicily. By now, the Italians were thoroughly fed up with the war and put up little resistance to the Allied landings. The Italian King, Vittor Emanuele III acquired some spine and determined to oust Mussolini and make peace with the Allies. At the Fascist Grand Council Meeting in July 1943, Dino Grandi, a leading Fascist, former foreign minister and Italian Ambassador in London, moved a motion requiring Mussolini to hand back some of his powers to the King. The motion passed by 19 votes to seven. The next day, the King ordered Mussolini’s arrest and installed Field Marshal Badoglio as head of a non- Fascist Government in Italy. Although, the Italians sent out numerous peace missions to the Allies, through Algiers and Lisbon, the Allies insisted on unconditional surrender. Essentially, the Allies passed up the opportunity to make a separate peace with Italy, which would have ensured Italian cooperation with landings on the Italian mainland. Such an arrangement would have allowed the Allies and the Italians to cut-off the means of withdrawal of German forces still fighting in Sicily and to strike at the Germans while their forces on the Italian mainland remained relatively week. While the Allies prevaricated, the Germans seized the opportunity to send fresh German Divisions into Italy. At 72 years of age, Badoglio simply was not up to the job and did little positive with his time in charge. When German, Field Marshal Kesselring asked for Badoglio’s permission to station more German troops on Italian soil, Badoglio failed to reply, so Kesselring went ahead anyway. German divisions now started pouring through the Brenner Pass and down into Northern and Central Italy.

Meanwhile, the Italian government continued to negotiate with the Allies, who refused to budge on the issue of unconditional surrender. Finally, the Italians sent General Castellano, already a veteran of several peace missions to Lisbon to accept the unconditional surrender, on the condition that the Allies would arrive in strength in mainland Italy. On 3 September 1943 in an olive grove at Cassible (Sicily), Castellano signed the instrument of surrender, which was to come into effect on 8 September. On the evening of 8 September, Badoglio announced the Armistice on Italian Radio. The trouble was that his speech was so vague that it left the Italian Army with no clear idea of what it was supposed to do. On 9 September, the Italian Royal family and Badoglio left Rome in a motor convoy to the port of Pescara, from where they were taken by the British Royal Navy to Brindisi.

Terror from the Air

Following the overthrow of Mussolini, the Allies pushed the Badoglio Government towards an Armistice by attempting to raze Milan to the ground. The city of Milan now found itself on the front-line of the war. Between 1940 and 1942, the RAF had occasionally bombed Milan, but their two engine bombers lacked both the range and the destructive capability. On 24 October 1942, the RAF had first used Lancaster Bombers on Milan, in their first and only daylight raid, They had done substantial damage but after that they had stayed away. 150 people were killed but little damage was done to industry or infrastructure. butt 150 people were killed. Italian anti- aircraft measures proved largely ineffective. In February 1943, the Lancaster returned, this time by night. That night, the British dropped around 110 tons of high explosive and 166 tons of incendiaries on the city. Targets again included Porta Genova and the Scala Farini railway yards, but they also managed to hit Alfa Romeo at Poltello, aircraft manufacturers Caproni at Taliedo and Isotta Fraschini in via Monte Rosa (by this time making aeroengines rather than luxury limousines). Bombs damaged the tram deport in via Messina and the bus depot in corso Sempione. Bombing was intense in Sempione area, with the barracks around via Mario Pagano, the nearby Arena also being hit. The offices of the Corriere della Sera in via Solferino, close to Porta Garibaldi were damaged, as well as cinemas and the Central Milk Depot, Artistic and culturally sensitive buildings damaged included the Palazzo Reale, the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana and Santa Maria del Carmine. 114 people were killed and over 10,000 left homeless.

The often bombed Isotta Fraschini factory in via Monte Rosa. Now peacefully used as an offices by an International accounting form, during the war it produced aeroengines.

The raids in August 1943 were of a different magnitude. They had a clear political motive to drive Badoglio to ask for an Armistice. The British intention was to create a firestorm in Milan and burn the city to the ground as they had been doing to German cities. On 8 August, the RAF commenced carpet bombing Milan for four nights with heavy use of incendiary devices. The raid on 8 August, did huge damage to large areas of the city, Porta Venezia, Porta Romana, Porta Garibaldi and Porto Ticinese. The Pirelli factories were badly damaged, and the Scala Farini was hit again. 60 buildings were destroyed and 161 people killed. Italian anti-aircraft fire was reported to be light and searchlights ineffective. However, one Lancaster bomber of 61 Squadron flying from RAF Syerston in Northamptonshire was hit by anti-aircraft fire and exploded, fallen wreckage was found in various parts of the city and the bodies of the crew were recovered on the ground.

On the night of the 12/14 August the British ramped up their efforts to destroy Milan. 504 Lancaster and Halifax bombers indiscriminately bombed the centre. The theatre of La Scala took a direct hit and was badly damaged, as were the nearby Palazzo Marino, the Questura in piazza San Fedele and the Galleria. The bombers also almost destroyed the church of S. Maria della Grazia (by some miracle Leonard’s Cenacolo survived, protected by a wall of sandbags). Fires raged until the morning, and firefighters from as far away as Bologna were rushed to the stricken city. The RAF had one final try on the night of 15/16 August when 199 bombers wrought further damage on the city centre, hitting La Scala again and collapsing the roof, and causing severe damage to the Archivio do State, the Duomo and the Rinascente department store.

After four nights of bombing, more than 1400 people had been killed, 50 percent of all buildings were damaged and around 250,000 were left homeless. The death toll was relatively low compared to the death tolls in German cities, because hundreds of thousands fled the city every night to sleep in the countryside. Milan was not razed to the ground. It was a city of strong stone buildings, with wide streets which acted as firebreaks and the conditions for an out of control fire never developed. The weather also saved the city, as anybody who has been the in summer can attest, Milan in August is hot and humid with almost no wind or air circulation, and those conditions almost certainly stopped the fires from spreading.

Milan occupied

On 8 September. the situation in the bomb-damaged Milan remained very confused. The city was as yet unoccupied by the Germans and was strongly garrisoned, The Italian officer commanding the Milan garrison, General Vittorio Ruggero sought urgent guidance from Rome about what to do. No coherent reply was forthcoming, so he confined the garrison to barracks pending further orders. On 9 September, the population of Milan came out onto the streets to celebrate what they thought was the end of the war; they were blissfully unaware that the government had no plans for defending the city and that the Germans were on their way. On 10 September, advance German units from the notorious Waffen-SS Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler entered Milan and positioned their armoured cars and tanks in the centre of the city. A proposal to create a citizen National Guard to defend the city was blocked by General Ruggero, who refused to distribute arms to the citizens of Milan, Meanwhile sporadic fighting broke out between some civilian groups who had obtained arms and the Germans in the central station area. By evening, the unfortunate General Ruggero, still waiting to receive any form of orders from the Government had little choice but to surrender the city to the Germans. On 11 September, the Germans entered the city in force and any opportunity for sustained resistance was lost. In the barracks of Milan, Italian soldiers began to don civilian clothing and head home to their families. On 12 September, the Germans captured General Ruggero, who was to spend the next 18 months in German captivity. For the people of Milan a long ordeal was just beginning.

Hotel Regina

After the Armistice, the various organs of the German Secret Police began to establish themselves in Northern Italy. Gruppe OberItalien “West” and the Aussenkomando ( AK) Mailand were set up after the Armistice. Separate AK’s were also set up in the principal cities of northern Italy Padua, Bologna, Parma and Venice. All reported directly to the German HQ in Verona. The Germans decided to group the important industrial triangle of Milan-Turin-Genoa under a special HQ, Gruppe OberItalien “West” based in Milan, this HQ then had it’s own AK’s in –Milan, Turin, Genoa and Novara as well as being responsible for border policing in north Italy along the Swiss border through the Grenzbefehlstelle West at Cernobbio. The staff of the Gruppe HQ and AK Milan arrived in September 1943 and established their HQ at the Hotel Regina in the centre of Milan, a few hundred metres from La Scala

In charge of Gruppe OberItalien “West” was SS Standartenfuehrer Walter Rauff. Too young to serve in the First World War, Rauff joined the Reichsmarine as a Cadet in 1924, subsequently working his way up to command a Minesweeping Flotilla. In 1937, Rauff left the Kriegsmarine as a result of a sex scandal. Fortunately for him, an ex-Navy Colleague, Reinhard Heydrich, now headed the SS Security Service, the SD. Thanks to Heydrich’s influence, Rauff became an SS candidate and trainee at the SD Hauptamt in Berlin, When the Germans occupied Prague in 1938, he went there with an Einsatzkommando, returning to Berlin to work in the technical section. In September 1941, Heydrich was appointed Deputy Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia and Rauff accompanied him to Prague as a technical specialist responsible for all SD communications. It does seem that Rauff’s technical work involved something rather more sinister than wireless telegraphy. There is evidence that he was involved in the development of the gas vans, originally used to asphyxiate Jewish and disable prisoners in the East. After Heydrich’s assassination, Rauff ended up in Tunisia with an SS Einsatzkommando, where he was involved in the rounding up of Tunisia’s Jewish population for forced labour. Following the surrender in May 1943, Rauff’s Einsatzkommando was deployed to Corsica, until in September 1943 he was ordered to proceed to Italy. This was the man who was now overlord of Milan.

While Rauff was responsible for the whole of the Milan, Turin, Genia triangle- his operational commander in Milan, the head of AK Mailand was Hauptsurmfuehrer Theodore Saevecke. Saevecke, also had a nautical background. A native of Hamburg, he had joined the German merchant navy, where he serving three years on the Hamburg to South America route. In 1934, he was invalided out if the Merchant Navvy with stomach ulcers and joined the Kriminalpolizei (Kripo) in Luebeck. He had already joined both the NSDAP and SA in 1929. Later he worked murder and arson cases in Berlin until 1939, after brief service in Poland he was posted to the Colonial Planning Office in Berlin. As part of this role he was assigned to the Italian Africa Police ( PAI) at the training school in Tivoli and then in Libya , sending reports on the organisation back to the Colonial Planning Office. When the Germans occupied Tunisia, Saevecke became Raff’s adjutant and was also deeply implicated in the round up of Tunisian Jews.

The Hotel Regina was both Rauff’s Gruppe HQ , from where he controlled also Turin and Genoa and the HQ for the AK Mailand under Saevecke. Roles were responsibilities were divided between various Abteilung which were themselves divided into Referat , mirroring the structure of the RHSA. Saevecke was given responsible for Abt IV (Gestapo) and Abt V(Kripo) in Milan. After Rauff and Saevecke, the most notorious figure in AK Mailand, was possibly SS Hauptscharfuehrer Otto Kurt Koch who headed Referat IV/4 of the Gestapo charged with anti-Jewish activities.

The former Hotel Regina . HQ of the SS/SD in Milan. Locals referred to it as the "Hotel Gestapo"

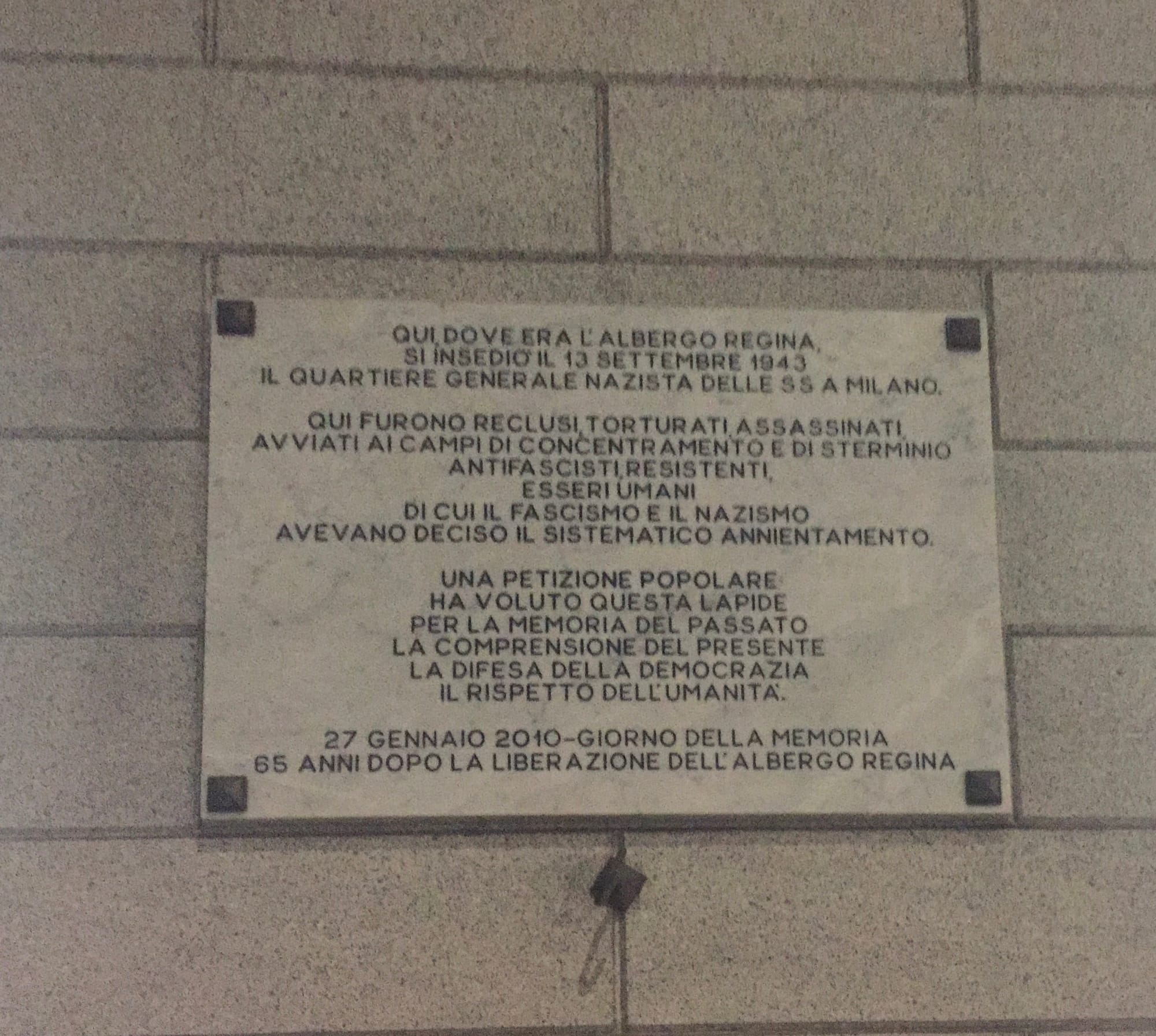

Memorial plaque at the site of the Hotel Regina

Occupied Milan

While Gruppe OberItalien “West” and the AK Mailand established themselves at the Hotel Regina, other German units established themselves throughout Milan. The German Consulate in Milan established itself in the prestigious confines of Hotel Principe di Savoia, in piazza Fiume (now known as piazza Repubblica). piazza Fiume was a hub of German occupation, the Platzkommandatour took over the Hotel Tunisia in the same area, while the Orstkommandatur went for the hotel Gran Turismo nearby. Nearer to the Central Station, the representatives of the German Armaments ministry the RuK. set themselves up in the comfortable quarters of the Albergo Gallia Excelsior.. German soldiers were quartered in numerous hotels in the Central Station area, taking over schools and other buildings to use as barracks and vehicle parks. The Feldgendarmarie (the German Army Military Police) took over the Casa di Riposa Giuseppe Verdi, which was previously a rest home for retired musicians. Also present in various parts of Milan, was the Organisation Todt, with its offices for the “recruitment” of labour for the Reich. In order to guarantee security, German and RSU units set up barracks in industrial complexes such as Innocenti and Caproni, they guarded the main train stations, Centrale, Garibaldi, Lambrate and Porta Vittoria and set up anti-aircraft positions around the city. Although the Germans were now Masters of the City of Milan, they depended on and worked with substantial numbers of Italians to enforce their reign of terror.

High school in via Venini, used as a barracks and vehicle depot by the Wehrmacht, Partisans bombed a nearby bar used by occupation forces.

The Repubblica Sociale Italiana

Since being deposed and rescued by the Germans, Mussolini had been hiding out in Germany and less than keen to return to Italy. Basically, the Germans gave him the stark choice, cooperate or see Northern Italy treated like Poland. On 18 September 1943, Radio Munich announced the formation of the Repubblica Sociale Italiana and on 23 September at the German Embassy in Rome, the new state was formally constituted. Even though Mussolini continued to remain Germany for the time being. It was unofficially known as the Republic of Salo after the lakeside resort where the Ministry of Culture and its Foreign Press Agency were located. Mussolini had wanted to establish the capital in Milan, but the Germans had vetoed that idea, ostensibly to not provide a target for further bombing. More likely they wanted to keep the government of the RSI divided and unable to govern coherently. So, the RSI government was dispersed as far a field as Venice, Verona and a number of resorts around Lake Garda.

On 18 December, 1943 the RSI established the Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana to take over responsibility for internal and military policing, In practice it took over the roles of the Real Carabinieri and the Milizia Voluntaria per la Sicurezza (MVS) and the Polizia Italiana Africana ( PAI) . In Milan, the GNR had its HQ in via del Carmine near to the Brera Gallery, in most parts of the city they operated out of former Carabinieri barracks in via Copernico (near the Central Station) , via Rovereto, via Bertolazzi , via Fiamma , via Arimondi and via San Giorgio. A separate Police force was established, the Corpo di Polizia Repubblicana, absorbing the civilian staff of the Ministry of the Interior and Corpo delle guardie di Pubblica Sicurezza. While it remained responsible for normal policing, it also included an anti-partisan role comprising six battalions organised on military lines. In Milan the Corpo di Polizia Repubblicana was based at the Questura in via Fratabenefratelli, with police stations spread across the whole city. The Squadra d’Azione (later the Legione) Ettore Muti formed in Milan after the declaration of the RSI, incorporated several existing Fascist squads. The Muti was originally charged with providing security for the newly opened PNF offices, but later expanded to supporting both the Germans and the Italian police. The Muti was on the radical side of Fascism, and often in conflict with the more moderate federale of Milan, Aldo Resegna, in December 1943, it was absorbed into the GNR as an autonomous unit. In March 1944, the Squadra was reborn as Legione Autonoma Mobile Ettore Muti with police functions and reporting to the Ministry of the Interior. Commanded by Questore Francesco Colombo, the new Muti ended up based in the heart of Milan, in via Rovello –again it had several outstations throughout the city.

In addition to all the various Police forces, other units of the RSI Armed Forces were based in Milan. In October 1943, the RSI founded its own Air Force , the Aeronautica Repubblicana . Following the armistice, many Italian pilots who stayed loyal to Fascism and the Third Reich wanted to continue fighting and planned to form a “foreign legion” within the Luftwaffe, with the grudging support of the Germans, 300 Italian pilots formed the nucleus of the new air force. In Milan, the ANR was based at the Air Ministry building in Piazza Italo Balbo. As well as fighter planes and transports, the ANR had also trained its own paratroopers, the Battaglione Azzurro. The RSI even established its own Navy. The Italian Navy, the Regina Marina remained the most royalist of all the services. After the Armistice, most of its vessels sailed to Allied controlled ports, while those few remaining in the North were either scuttled or handed over to the Kriegsmarine. The reconstituted Republican navy, held a very small fleet of Motor Torpedo boats and Midget Submarines, mainly based around Venice. Before the Armistice, the Decima MAS had been part of the Navy, famous for its exploits against British Shipping. Afterwards many of its members in the north had sided with the RSI. Commanded by Captain Valerio Borghese, the Decima MAS became a land unit and occupied with anti-partisan duties and with defending the North East of Italy. The Decima MAS also had several bases in Milan, with a HQ in piazza Fiume, and a press and propaganda office, sharing quarters with the Germans in the nearby Albergo Nord.

In Milan the Germans had dealings with all these paramilitary and auxiliary police forces, not to mention some outright gangs. These included the political office of the Legione Muti, the investigative section of the Brigata Nera Resega, the investigating office (UPI) of the GNR. Then there were special units of the Republican Air Force and Navy, including the Decima MAS. Finally there were a number of highly irregular gangs, such as the banda Koch, banda De Sanctis, banda Politi, and banda Finzio, which had emerged from the woodwork after 8 September or had migrated from the Allied occupied zones.

San Vittore prison in Milan. Used by the Germans to detain their prisoners prior to deportation

The Vanquished

The fate of General Vittorio Ruggero was shared by hundreds of thousands of Italian soldiers captured by the Germans following the Armistice. It has been estimated that somewhere around a million Italian soldiers were captured sand disarmed by the Germans after the Armistice. These included some 35,000 soldiers in Southern France and around 430000 in the Balkans, Greece and the Greek islands, the remainder being taken in Italy. Of these 1 million men, around 196,000 managed to escape, disappear or were released. A further 94,000 opted almost immediately to join the RSI. Sime 13,000 were tragically drowned as a result of British attacks in German ships evacuating them from the Greek islands. All told around 710 to 716,000 Italian soldiers were deported to Germany. When you add the 380,000 Italians who were legitimately being held Prisoners of War by the British, then all told over 1 million Italian men were being held prisoner outside Italy in September 1943. Added to the deprivations of the war, many families in Milan experienced the misery of having their fathers, husbands or sons imprisoned in foreign prison camps.

Typical of the Internees was Viginio Rioli from Milan. At the time of the Armistice he was serving with the 4th Corpo Armata in Albania. On 8 September, Italy had hundreds of thousands of troops occupying, the South of France , Greece, Yugoslavia and Albania . When Badoglio announced the Armistice, 130,000 Italian soldiers became trapped in Albania. Now at its nearest point, Albania is only around 30 miles from the Italian coast and the port of Brindisi which at the time happened to be occupied by the British and open to the Badoglio Government. Some Italian troops were evacuated by the Italian navy across the narrow straits, the rest were taken into German captivity.

Considerable numbers of the Italian soldiers who had escaped capture by the Germans went on to join Partisan units. One notable figure was General Guiglielmo Barbo. Born in Milan on 11 August 1888, he was scion of two noble Italian families. In 1909 he from the Italian Military Academy at Modena, the Italian equivalent of Sandhurst and sent to the cavalry School in Pinerolo, before being assigned Barbo was assigned to the prestigious 1s Regiment Nizza Cavalleria. In the First World War on the Allied Side in May Barbo saw distinguished service with Cavalry on the Giulian front. He was decorated for his services around Monfalcone in 1915 and won an Italian Military Cross for his services during the final Italian offensive in November which crossed the Tagliamento river and liberated Udine. He stayed in the Army after the war and by 1 April 1938, he had risen to command his old regiment m the 1 Nizza Cavallaria. In this role, he took part in the Italian invasion of France in June 1940 and later in the invasion of Yugoslavia. After some time on the General Staff , Barbo was put in charge of the 3rd Regiment Savoy Cavalry. That regiment was sent to Russia as part of the ill-fated Italian Expeditionary Force (CSIR). Barbo was decorated for his services, for actions along the River Don in August 1942. In November 1942, Barbo returned to Italy where he was put in charge of the Cavalry School at Pinerolo, Following the armistice, the Germans arrested all the officers and men at Pinerolo and sent them to Germany. Barbo escaped from that internment train and joined the partisan forces in Piemonte. In the end, he was captured on 16 August 1944 and sent to San Vittore Prison. Subsequently, he was sent to transit camp at Bolzano and then as a political prisoner to the concentration camp at Flossenburg. Broken by the conditions in the camp, Barbo died there on 14 December 1944, aged 56 years.

General Barbo's family home at via Visconti di Modrone, 20. Milan

The stolperstein for General Barbo outside the family home

Resistance begins

Although the chances of an immediate mass insurrection to defend the city against the Germans had been lost, various resistance movements sprang up in Milan ranging from the Liberal to Communist. The Gruppi d’Azione Patriotica , were part of a dual policy of the Partita Communista Italiana (PCI) – on the one hand they would wage an economic war on the German occupiers and their Italian collaborators through Industrial action and the other hand they would engage in an armed struggle against the occupation. In September 1943, Francesco Scotti and Egisto Rubini, together with a number of workers established the GAP in Milan. Active gappisti, shared a common background, often including participation in the Spanish Civil War, prison or internal exile in Italy; and membership of the French Resistance. After the armistice many of those who had been fighting with the French resistance crossed back into Italy to continue the armed struggle there. With such a shared background, many of the active gappisti were well suited to a clandestine existence in an occupied city. Apart from the veterans of the Spanish Civil War, may gappisti had little experience with an armed struggle, they were under armed and their early efforts were faltering. they picked it up as they went along changing their tactics, according to what was successful and the resources available. Nevertheless, the soon started to make their presence felt. On 4 October, they claimed their first victim, a sergeant major in the squadristi shot to death near the Pirelli plant. A few days later they scored a bigger coup, assassinating a Major from the GNR right outside the Villa Reale in Monza, which at the time was the HQ for the SS in Lombardy. Such an audacious stroke right outside the nerve centre of German power in Lombardy, proved the ability of the gappisti to strike at will.

The first fortnight in November 1943, the pace of attacks increased. Two German soldiers were beaten to death with hammers in Piazza Argentina, on corso Buenos Aires. Proving that in the absence of guns, the gappisti could be a lethal force. On 5 November, the gappisti carried out the first of what would become one of their hallmark operations, the bombing of restaurants and bars frequented by the Germans and their Fascist allies, two Germans were killed. The German information Office at the Stazione Centrale was bombed establishing the station as one of their frequent targets. Particularly common were attacks on lone German soldiers or Fascist militiamen out and about in Milan. To some extent the attacks were designed to provoke a German response and to start with the Germans steered clear of overt reprisals, they even liberalised the curfew time until 11 pm, and allowed the reopening of theatres and cinemas. The Germans had taken over a school in via Venini , not far from the station to use as barracks. German soldiers and Italian Fascists frequented a cafe in the same road, so the gappisti bombed that. They sabotaged tramlines. From their strongholds in Sesto San Giovanni and North Milan, gappisti attached German vehicles heading northwards out of Milan along the viale Zara.

The Central Station in Milan became the target of numerous partisan bombings. Behind is the luxury Albergo Gallia, where the German Armaments Ministry established offices

In December 1943, a wave of strikes started in Milan. Conditions were terrible, wages were poor, hunger was widespread, and all were exacerbated by the cold weather.Instigated by the PCI, workers at the important aircraft factories of Caproni and Magnani went on strike. The strikes soon spread through the steel , metalwork and other industrial sectors in Milan and Sesto San Giovanni. Workers demanded a 100% increase in wages, better canteens and better rations. Surprisingly, the Germans were moderately sympathetic to these demands, after all it was the Italian industrialist who would paying, not them, Nevertheless, they stepped up intimidation tactics, stationing armoured cars outside the most strategic factories and starting arbitrary arrests.

On 18 December, the last day of the strike the gappisti pulled off their biggest spectacular. The Fascist federale of Milan, Aldo Resega was gunned down in the street in broad daylight. Fascist revenge was swift with eight imprisoned partisans taken out and murdered at the Arena on 19 December. The eight men had all been imprisoned before Resega’s assassination, so had had absolutely nothing to with it. On the morning of the 19th they were taken from San Vittore to the Palazzo di Giustizia and at 14.30 went before a Military Tribunal headed by the questore Camillo Santamaria Nicolini, without much in the wat of due process and with no defence being allowed they were sentenced to death. The sentence was carried out by men from the Legione Muti. The eight men refused to die sitting down and as the order to fire was given, they all stood up to die standing, shouting Viva Italia.

The Arena in Milan. Built in Napoleonic times. In the 1930s , Internazionale played football there. During the war it was used for more sinister purposes.

Memorial to the eight men shot at the Arena in December 1943

Memorial to the eight men shot at the Arena in December 1943

The next day Resega’s funeral in the centre of Main turned into chaos, and a bloodbath was only prevented by the intervention of the SS. The Fascists were determined to use Resega’s funeral in the centre of Milan as a show of strength and blackshirts poured into the city from all over Lombardy to follow the funeral cortege. They were armed to the teeth. The gappisti had found out the route of the cortege and were hiding out in some abandoned buildings, which overlooked the route. They started to fire on the crowd, who panicked. The blackshirts returned fore against unseen assailants, firing off an estimated 5000 rounds of ammunition. Surprisingly there were few casualties and general order was restored following the arrival of a detachment of the SS

In early 1944, the journal “Il Combattente” published the balance of the GAPs activities in its first three months of existence. 150 Germans had been killed and hundreds injured, 21 Italian Fascists had been assassinated in the same period. Countless damage had been done to infrastructure, German vehicles and the fabric of the city during the bombings. Only three partisans had been killed in action. The GAP started 1944 with a gun attack on a car carrying the questore Camillo Santamaria Nicolini (who presided over the sham trial for those short at the Arena). He survived, perhaps was a sign that the New Year was not going to be so successful for the GAP, for in February and March 1944 they suffered a number of setbacks and mass arrests.

Il Fronte della Gioventù

The GAP were not the only resisters and resistance took other forms than armed struggle. In January 1944, Eugenio Curiel established Il Fronte della Gioventù per l’Indipedenza nazionale e per la libertà. Curiel was a veteran communist organiser who had been exiled in Paris and who had returned to Italy, been arrested and served the usual sentence in the prison island of Ventotene. He envisaged a non-denominational resistance movement based on democratic values and open to youth of whatever political tendencies. The first meetings of the front were held in the sacristy of the Church of San Carlo al Corso (in the centre of the corso Vittorio Emmanuele) . The activity was encouraged by two anti-fascist priests, Camille De Piaz and David Maria Turodo. By the summer of 1944, the Fronte had expanded throughout the schools and universities of Milan and then throughout the country.

One of Curiel’s collaborators in the Fronte, was a teacher prof. Quintino Di Vona, Di Vona won the Silver Valour Medal during the First World War, which permitted him to stay teaching without having to become a Fascist Party member. Di Vona was a renowned Classics teacher, who published Cicero and Tacitus, as well as translating Heine from German to. In 1933, he was appointed as a teacher of classics at the Liceo Classico Carducci in Milan. The Liceo was in via Tullio in the heart of one of Milan’s working-class areas which later become the heartland of resistance activity. Di Vona was politically suspect to the Fascists so they demoted him from the ginnasio superiore to the ginnasio inferiore (the middle school) in via Sacchini; However, he was such a good teacher that they could not get rid of him. He was even invited to a national convention on Latin organised by the Fascist Regime. Apparently, he turned up for his presentation in a white short rather than the normal Blackshirt. After the Armistice, Di Vona’s anti-fascist activities increased, with involvement in the CLN Carducci and with many underground publications. He also seems to have inspired several his pupils to commence activities with the Fronte. In January 1944, a squad from the Legione Ettore Muti burst into the Liceo Carducci ostensibly on a recruiting mission for new volunteers for the RSI, instead they started attacking students. One of these was a certain Enzo Capitano, who was taken away for further brutal questioning by the Legione.

Deportations

On 6 December 1943, the first of 23 deportation trains left Milan from Binario 21 of the Central Station , it was bound direct for Auschwitz and carried 250 Jews who had been rounded up in Northern Italy .They came from Genoa, San Remo , Bordighera and Turin as well as a number who had been picked up at the Swiss frontier and were assembled at San Vittore prison and when there were enough of them were taken by truck to the Central Station, When the station had been build , they had constructed an underground platform from which the mail could be loaded into rail wagons, the wagons were loaded into elevator to be lifted up to the tracks. The Germans used the same system for far more sinister purposes. Prisoners were unloaded from trucks outside the station, then being abused, beaten, and attacked by the dogs of the German guards they were herded into the underground part of the station, where they forced them into cattle wagons between 60 and 100 in each truck. When the wagons were full, they were lifted up onto the railway line to be hitched to trains. Another train of Jewish deportees bound for Auschwitz left on 30 January 1944. However, it was not just Jews who were deported from the station, trains loaded with Italian political prisoners, strikers and others who had fallen foul of the regime went straight from the station to the terrible work camp at Mauthausen-Grusen and its associated sub camps. Other trains lefty Milan for the Italian Transit camp at Fossoli and later (when Fossoli had fallen into Allied hands to the Transit camp at Bolzano before going to their destination. On 19 April 1944, a train of Jewish deportees went straight to Bergen- Belsen. Binario 21, allowed the Germans to conduct their activities away from the public eye. Prisoners left San Vittore at dawn to travel through the deserted streets to the Central Station, where they were loaded far away from the other passengers using the station. The last deportation train left Milan on 15 January 1945.

The underground entrance to Binario 21 at Milan Central Station. This was the entrance the Germans used to take their victims to the underground platforms

One of the original cattle wagons used for deportations in the underground complex of Binario 21

Strike

By March 1944 Milan was a thoroughly miserable place to be. The Italians had been unable to repair the damage done by the August 1943, bombings, the population had dropped dramatically as hundreds of thousands who had fled the city stayed in the relative safety of the countryside, thousands were homeless , services were disrupted and thousands of families were missing their fathers, husbands and sons who were languishing in British, German and Russian prison camps. The city was effectively in a state of civil war between the RSI and the resistance movements, there were bombings and shootings daily and an atmosphere of repression everywhere. Through it all the Germans remained masters of the city with the SD HQ in Hotel Regina being the worst place to finish up. It really looked like things could not actually get much worse, but of course they did.

The economic situation for the RSI was looking pretty grim. Any initial enthusiasm for the return of Mussolini and his new regime was starting to wear thin. The still functioning parts of Italian industry were being used almost exclusively for the benefit of the Germans, while non-essential industries had been shut down and their plant sent to Germany. Far from treating the RSI as an ally, the Germans were treating it much like any other occupied territory. The Germans from the RuK called the shots for Italian industry, cutting out the structures of the RSI and negotiating directly with the big Italian industries, ordering directly, fixing prices and allocating raw materials. Totally ignoring any Italian civil or military needs. Industry was suffering from extreme shortages of raw materials, especially coal on which Italy was almost totally dependent on German imports. The Germans only gave the Italians about half what they needed. Electricity production was well down, affected by lack of coal, the effects of a drought on hydro/electric production and allied bombing of power stations. Transport was totally fragmented and disrupted as the Allies bombed oil refineries, vita railway junctions and marshalling yards and port installations. With the disruption to raw materials and power supplies, many industries were forced to lay off workers or bring in reduced hours. Even the salary increases gained in the previous strike had been eaten up by inflation, the black market and general food shortages, the situation might best be described as extremely difficult

On 1st March, a general strike started in the industrial triangle of Milan. -Turin-Genoa. Workers at the great factories of Milan started to go on strike. In the industrial sector, the figures were impressive 9,500 workers on strike at Pirelli, 14,000 at Breda, 8,700 at Falck, 6300 at Alfa Romeo, 3000 at Magnetti Marelli, 2800 at Innocenti, 2800 at Caproni. In addition workers were striking at Edison Power, the Gas Company , the Corriere della Sera newspaper and at ATM which operated Milan’s tramway system.in all, the GNR reckoned that some 210,000 workers were striking in Northern Italy, with 119,000 in the Milan area, The Germans actually estimated the number as higher,. German ambassador to the RSI, Rudolf Rahn was demanding that 70,000 striker or 20% of the total be deported to Italy, thus putting the estimated number of strikers around 350,000. It was the biggest Industrial action in German occupied Europe. As soon as the strike started the RSI moved an extra six companies of the GNR from as far away as Mantua and Verona into Milan to keep order and suppress the strikes. On 2 March, the GNR occupied key factories. A GNR bulletin of 2 March described the situation.

“Because of the strike, the tram service in Milan is suspended. The only vehicles circulating are those driven by volunteers of the Battaglione Muti. The factories of Breda in Sesto San Giovanni, Alfa Romeo, Pirelli and Caproni have been occupied by the military, Up until new there have been no incidents. The GNR has arrested 62 persons, compromised on political lines and made then available to the German authorities for internment. Investigations continue.”

For the next few days, the situation remained stable. The GNR and various Fascist bands continued to round up suspected activists, the factories remained occupied and the workers stayed at home, The GNR noted mass leafletting campaigns in Milan, urging workers to stay at home. By 9 March, the strikes were ended and the GNR bulletins noted that the situation was returning to normality was a normality based on repression and terror. During the first few days of the strike the GNR and its associates had arrested over 150 people and handed them over to the Germans. In fact, the Germans did very little to repress the strike, perhaps due to their lack of resources in the area, they were largely content to sit back and wait for the Italians to handover prisoners before deciding who was to be executed or deported or even released. In the end Rahn did not get his 70,000 deportees due to convenient “technical and transport issues”. More likely the Germans were aware that Italian industry which was still vital to their war effort would collapse with 70,000 skilled workers deported, nevertheless some 1500 to 3000 strikers were deported to Germany, including over 500 from Milan.

Among those deported was Angelo Fiocchi. Born into a working-class family in the Lambrate District of Milan in 1911. Angelo was married with a daughter; he got a job with Alfa Romeo as a messenger and an apartment in the model residential complex in viale Lombardia. The apartment complex was known to the authorities as the Casbah, once inside a fugitive could disappear among the courtyards, stairwells and the apartments of sympathetic neighbours. Angelo became involved in the strike at Alfa Romeo in March 1944, part of a wider industrial action which shut down the great industries of Milan for eight days. He found out his name had been betrayed to the political Police and planned to escape to the partisans in the mountains. Before he could leave , he was arrested and taken to San Vittore and then to Fossoli. On 8 March 1944 , he was on a train from Fossoli, which arrived at Mauthausen on 11 March, thereafter he was transferred to the camp at Ebensee working in the underground galleries. He there on 7 April 1945, a month before the camp was liberated.

Angelo Fiocchi lived at this model residential complex , viale Lombardia 65

Enter “Visone”

In March 1944, Giovanni Pesce nome di guerre “Visone” arrived to take command of the GAP in Milan. Pesce was a native of Piemonte. In 1924, aged six years old his family had taken him to live at Grande Combe in the France where his father had found work as a miner. Pesce grew up there as an exile, surrounded by a cosmopolitan workforce of Germans, Slav, Poles and Algerians. In 1931, Pesce went to work in the mines himself, in 1936, he left for Spain to serve with the International Brigades, which he did with distinction being wounded twice. When the International Brigades left Spain, he went back to France and with the German occupation of France, joined the French Resistance. He then returned to Italy to take up resistance against the Germans in Piemonte.

In the summer 1944 the GAP commenced a new offensive, this was especially and effectively directed at German lines of communication, telephone lines, electric cables, railways and road traffic. A particular focus was the vital railway junction at Greco- Pirelli, this not only controlled the railway lines North of Milan towards Como and Switzerland, but was also an important repair yard used to bring back into service, rolling stock which had been damaged in Allied bombing attacks. On 6 June, the gappisti struck at Greco-Pirelli. With some help from inside men among the railway workers, they were able to destroy five locomotives and other rolling stock as well as a fuel dump. At a time, when the Italian rail system was really suffering the effect of allied bombing the loss of even five locomotives should not be underestimated. As a result of the attack on Greco- Pirelli, the authorities rounded to three rail workers who had been guilty of no more than anti-fascist leafletting and had them shot A further high profile attack on German communications was launched at the airfield at Bresso, which the Germans were using to fly air support to anti-partisan operations in the mountains of Lombardy and in Piemonte. The gappisti killed two German sentries and using only Molotov cocktails managed to destroy one German transport aircraft and severely damage two others. On 6 August, gappisti caught and killed Captain Marcelo Mariani from the Railway Militia who had been responsible for the execution of the three railway workers following the first Greco-Pirelli attack. At the end of August, they struck the Central Station again, blowing up a cafeteria used by the Germans and Republican Militiamen.

Allied Agents

The resisters in Milan, were not working alone. They received considerable financial assistance and war materiel from the Allies, from the British Special Operations Executive ( SOE) , with their mission “to set Europe ablaze” and from the American OSS. Both organisations trained Italian Agents and parachuted them back into Italy. One such agent who originated In Milan, was Guglielmo “Mino” Steiner. Mino was the the son of a rich Milan industrialist originally from Bohemia, Having graduated in Jurisprudence, Mino began working for the anti-Fascist lawyer Basso at his studio in viale Bianca Maria. First arrested in 1939, as a result of his association with Basso and antifascist circles and he spent a week in San Vittore Prison. Later Mino was conscripted into the Italian Army and was in Sicily when the Allies landed. He was put in contact with the British, who recruited him and put him in charge of Mission Law, which was intended to gather information on German forces and to help Allied prisoners behind the enemy lines help to get to safety in Switzerland. Mino was landed by a British Submarine, HMS Sickle on the Italian, near Sestri Levante. In Genoa he recruited further agents for Mission law and then made his way to Milan. Lying low in Milan, he contacted local members of the Action Party and became involved with the clandestine press. After the General Strike in Milan on 1st March 1944, a number of members of the Action Party were detained by the Germans , including the party secretary Mario Damiani. They tortured Damiani, who was in the possession of many names of party members. Mino was picked up on 16 March 1994 and held in solitary confinement for 28 days, while subject to repeated interrogations. On 27 April 1994, he was sent to Fossoli and deported to Mauthausen. There he was transferred to the work/ extermination camp at Ebensee, on the back-breaking work of conducting the bomb proof underground tunnels. He died on 28 February 1945.

Stolperstein for patriot and British Agent Mino Steiner at viale Bianca Maria 7

The Massacre of Loreto

At 8,15am on 8 August 1944, a German soldier Heinz Kuhn was dozing in his army lorry outside viale Abruzzi 77 when two devices exploded near his truck. At the time, there were large numbers of German troops billeted in various requisitioned hotels in the area, especially at the Albergo Titanus , a large hotel at intersection of the Piazzale Loreto and viale Abruzzi It is likely that Kuhn had arrived to pick up a detachment of German troops for duty in the city. Kuhn was only slightly wounded, and no other German personnel were involved. Ix Italians were killed at the scene and eleven wounded. Giovanni Pesce always denied that the bombing had been carried out by the GAP or any other partisan grouping. There is always the possibility that it was a “false flag” operation by the Germans designed to lessen popular support for the partisans and allow the Germans an excuse for reprisal. The German authorities appear to have made no serious efforts to find the actual perpetrators of the bombing

Viale Abruzzi 77, where persons unknown blew up a German truck.This led to the Massacre in piazzale Loreto.

Instead Saevecke drew up a list of those imprisoned in San Vittore. At dawn on 10 August, fifteen prisoners were taken from San Vittore across Milano the piazzale Loreto. At 6,10 they were shot by a platoon from the Legione Ettore Muti. Most probably they were acting on the orders of Saevecke, or at least with his blessing. The Italians could not do much without asking Saevecke first. The slain were left where they fell throughout the course of a long hot summer day. The purpose was intimidation fir the many Milanese who had to pass piazzale Loreto on the way to work. A sign identified the deceased as being assassins, the men from the Legione Muti stood guard and prevented anybody (even family members) from paying their respects to the dead, they forced people who turned away to look at the bodies. The killings in piazzale Loreto and the subsequent mistreatment of the bodies had a deep effect on Milanese public opinion, the Fascist Prefect of Milan and the head of the Province of Milan, Parini sent an urgent memo to Mussolini at Salo, complaining that:

“ the methods of the shootings was so irregular and against the law. The victims did not even have the assistance of a priest which would have been given to the most abject murderer- In answer to my intervention , the Nazi commanders all relied in the same way ; the execution was the application of the Kesselring decree,”

In her memoirs Mussolini’s wife, Rachele recalled that , while at Salo, she had received an anonymous letter with a poem that repeated the lines “We will take you all to the Piazza Loreto”. Apparently, she told chis mistress Claretta Petacci, “They will take you to the Piazza Loreto”.

Memorial to the partisans murdered in Piazzale Loreto, August 1944

Gorla

On 20 October 1944, three waves of US bombers left airfields in the Foggia area for bombing missions over Milan. Contrary to the previous British policy of carpet bombing, the USAF in Italy had a policy of “precision” bombing of specific targets , Two waves of bombers hit their targets including the Isotta Fraschini and Alfa Romeo plants, the mission of the third wing of 451 Bomb Group with 36 B24 bombers went horribly wrong. The mission was to bomb the Breda engineering works in Sesto San Giovanni. Due to a navigational error, rather than turning towards the Breda plant, they turned away. Unable to correct their error in time, they abandoned the mission and headed home. For safety reasons they were unable to land at Foggia with a full bombload and the normal protocol would have been to dump the bombs over the countryside or into the Adriatic Sea. Instead the bombers released their whole payload over northern Milan. At 11.29 am, nearly 80 tons of bombs were unleashed over the quiet Milanese suburb of Gorla. One of the bombs scored a direct hit on the elementary school “Francesco Crespi” in via Fratelli Pozzi , Gorla. 184 children between the ages of 6 and 12 were killed, in addition their headmistress, 14 teachers and 5 other adult staff were killed.

Autumn 1944

While the American delivered death from the air, the gappisti continued their campaign on the ground. In October 1944, they exploded a bomb at Rogoredo Station which paralysed southbound train traffic for two days (Rogoredo was and still is a vital part of the Italian train network for trains heading south to Bologna and Florence). A few days later they struck the garages of the Decima Mas in piazza Fiume, in one of the most heavily guarded parts of the city and centre of numerous German and Italian installations. Less than a kilometre away, they destroyed four German vehicles parked outside the restaurant Firenze in via Lazzaretto. In Piazzale Loreto, they destroyed an anti-aircraft searchlight battery.

Resistance came from all sides of the social and political spectrum. Roberto LePetit was born into distinguished family of chemical engineers of Swiss/French origin. His grandfather Robert George LePetit was famous for the discovery of aniline blue ( a substance used extensively for dying silk) . in 1867, Robert LePetit transferred to Milan founded the company of LePetit and Dolifuss. When Roberto’s father died suddenly in 1928, the company was on the verge of expanding into the Pharmaceutical business. Roberto took the helm of a company which now had 16 production plants in Italy, and which was present in 36 countries throughout the world

Roberto had become a card-carrying member of the PNF in the 1930s, he had to do that to stay in business. In 1942, he was expelled from the party. Following the Armistice he became actively involved with the partisans , especially providing financial support to them Unfortunately, he was rather too prominent and the SS had a look out for him, he spent a lot of time hiding out near Lake Como ,occasionally visiting Milan for partisan and for business activities. On 29 September 1944, he was arrested at the company offices at via Carlo Tenca, 30, He was taken to San Vittore. And then followed the usual sad route to Bolzano, to Mauthausen and to the awful sub camps at Melk and Ebensee. He died on 4 May 1945 at Ebensee, just as the camp was on the verge of liberation.

Although heavily refurbished. LePetit's office and factory is still in via LePetit. This part of the street ( formerly via Carlo Tenca) was renamed in his honour

The LePetit residence at via Benedetto Marcello 8

Cadorna arrives

On 12 September 1944, a British Halifax bomber dropped a distinguished parachutist in Val Cavallina, in Bergamo some 40 km from Milan. General Raffaele Cadorna was the son of Field Marshal Luigi Cadorna, who had been Italian Commander-in-Chief during the First World War. Cadorna was on a special mission to provide military Advice to the CLNAI. Graduating from the Accademia Militare di Modena in 1909, Cadorna seen service in Libya, during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911, and subsequently during the First World War. At the start of the war, regarded as politically suspect he had a minor involvement with the Italian invasion of France and then had then returned to command the Cavalry School at Pinerolo. At the time of the armistice Cadorna commanded the Armoured Division “Ariete II”, which was one of the few Italian units to offer serious resistance to the Germans in Italian at the time of the occupation of Rome. Cadorna was a conservative and convinced anti- Fascist, who had opposed the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, he also had a more internationalist outlook from his experiences outside Italy. His clean record made him an acceptable choice to both the communists and liberal elements of the resistance. Even so , he was to face considerable difficulty in getting all the disparate resistance groups unified.

The Jewish Population of Milan

Since the Risorgimento, Italy had not been a particularly anti-Semitic country. National Unification in 1861 had entailed the closing of the ghettos and the granting of full civil rights to all citizens regardless of religious belief. Many of Italy’s Jews played a prominent role in the rise of Fascism – there were five Jews at the piazza San Sepolcro, three Jewish Martyrs for the Party cause before 1922 and 230 who officially participated in the March on Rome. By the 1930s, it was estimated that around a quarter of Italy’s adult Jews belonged to the Fascist Party. From August 1938, the regime introduced a series of racial laws banning Jews from being scholars or teachers in Italian schools or universities, from serving in the armed forces, from having Christian servants and from marrying Christian “Aryans”. There is no evidence, that any of this was done under pressure from the Germans. On 7 September, Royal Law n 1381 concerning the Expulsion of Foreign Jews , established that from that date foreign-born Jews were forbidden from establishing their abode in the Kingdom of Italy, Libya or the Italian Aegean Islands; revoked Italian Citizenship granted after 1 January 1919 to any foreign Jews and provided that any foreign Jew in Italy, Libya or the Aegean Islands who became resident after 1 January 1919 be required to leave within six months of the publication of the Law or be expelled. .

Clearly many of Italy’s Jewish population who needed to work or study left the country; however, a large number remained especially the elderly. In fact as the was progressed, a number of foreign Jews took refuge in Italy. In Italian occupation zones in France and the Balkans, the Italian Army had largely protected the local Jewish populations from the excesses of the Germans and some Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe had even made their way to Italy during the war, notwithstanding the prohibition ion foreign Jews. For three years, Italian Jews continued in this limbo – subject to the Racial Laws and a degree of persecution, but not under threat of extermination or deportation(so long as they were pre 1919 Italian citizens) . The situation changed dramatically in 1943 when the Germans entered Milan.

Soon after Koch had arrived in Milan, he obtained a lost of all the registered Jews in Milan from the Questura. These lists had been compiled after the Racial Laws were enacted and contained the names of around 7,500 Jews in Milan, the vast majority being Italian citizens, but also German Spanish and Turkish Jews. Since the list had been compiled in 1938, and many of those listed had moved or left the country, the Germans were forced to use informers to supplement the list.

The synagogue in via Guastalla. Unfortunately, it is still surrounded by heavily armed troops. This time they are protecting it.

Milan’s Jewish community had been worshipping at the Synagogue in via Guastalla since its construction in the 1890s. In August 1943, the Synagogue had been hit by Allied bombs and heavily damaged, but it continued as a place of worship. On 8 November 1943, two men in civilian clothing knocked on the front door. Thinking them to be refugees, the custodian admitted them, however, they were followed by a patrol of SS men who burst through the doors into the rabbi’s office and arrested the fifteen people they found inside. Araw Lazar, a Bulgarian refugee was shot while trying to escape. The Germans ransacked the synagogue looking for valuables and took away the prisoners. They were taken first to Koch’s offices at the Hotel Regina where they were stripped , beaten and tortured then they were taken to the Jewish wing at the San Vittore Prison to be deported. Koch’s progress clearly was not good enough for the SS, and in July 1944 they sent a commission to help with the Jewish question. The commission was led by the notorious SS Hauptsurmfuehrer Franz Stangl, who had been commandant of both the Sobibor and Treblinka extermination camps, before being transferred to Trieste. Stangl was accompanied by his henchmen, three of whom Polizeimeister’s Kuettner and Gomerski and PoizeiOberwachtmeister Post, stayed on in Milan. They set up the Kommando Kuettner in an office on the corso del Littorio ( now corso Matteotti) and there with the assistance of an Italian informer known by the false name of Dr Manzoni, they operated independently from Koch and his men at AK Mailand in rounding up Milan’s Jewish population.

One Jewish family who stayed on in Milan, were the Reinachs. Ernesto Reinach probably thought he was too old for the Germans to bother with, The Reinach family lived in an upmarket residential street, via de Togni just off the via San Vittore. Ernesto’s family business was Ernesto Reinach Lubrificanti which produced industrial lubricants. As the Italian automobile industry developed, the company branched out into automotive lubricants, especially with the name “Oleoblitz”. It soon became famous throughout Italy , thanks to the company-s publicity appearing on Touring Club of Italy maps. Oleoblitz it was the official lubricant for the legendary marque of Isotta Fraschini and became associated with the great early years of Italian motorsport. Reinach’s daughter Maria married at noted Turin lawyer Ugo de Benedetti who moved to Milan. They had two sons, Giancarlo and Piero. By autumn of 1943, the family were feeling unsafe in German occupied Milan. The family had a country villa at Lanzo D’Intelvi in the hills above Lake Como, from where you could literally walk into Switzerland from the back garden. One by one the members of the family had already safely crossed into Switzerland using that route. They were helped by the custodian of the Villa, Giuseppe Grandi. While the Fascist gangs of Milan collaborated with the Nazi occupiers and did substantial amounts of their dirty work, ordinary Italians like Grandi shine out as a beacon of hope. In the end he paid with his life. He too denounced by someone, arrested by the Germans and died at Buchenwald.

Ernesto Reinach was one of the last to leave, but in the end at the beginning of November 1943 he and the remaining family in Italy packed up the big old Isotta Fraschini to make their escape. They made it as far as Torrigia a small town on the shores of Lake Como from where the road goes up into the hills towards Lanzo. They were literally less than hour from freedom, when of November 1943, Ernesto Reinach, Maria, Ugo de Benedetti and Piero de Benedetti were arrested by a German patrol. They were first taken to San Vittore Prison. On 6 December 1943, they were taken to Milan Central Station and loaded onto the train for Auschwitz. 88-year-old Ernesto Reinach died on the train. Maria Reinach De Benedetti, Ugo de Benedetti and 15-year-old Pietro de Benedetti arrived at Auschwitz on 11 December 1943. They were most probably gassed immediately on arrival. Piero’s brother Giancarlo was not with the family, he had been receiving treatment at a medical institution and was not with the family when they left Milan. In the end with the help of family friends and some benevolent Italians , he was eventually smuggled across the border into Switzerland and safety.

The Reinach family home in via Togni

Another who thought he was probably too old for Otto Koch and his minions to be bothered with was 87 year old scientist Michelangelo Boehm. He graduated in engineering from the Polytechnic of Milan. He married Margherita Luzzato and they had three children. The family lived in the comfortable residential street of via De Amicis, between Sant Ambrogio and the Navigili in Milan. Michelangelo Boehm had assisted the Italian War effort in World War with gas supplies, he was nominated as the Italian Vice-president of the International Gas Union in 1932. In 1935, Boehm received one of Italy’s highest honours being appointed an Officer of the Crown of Italy. In 1938, Italy’s Racial Laws ended Boehm’s long and distinguished career . He was no longer able to teach at the polytechnic, his honours were removed. He and Margherita retired to private life in the mountains above Lecco. Meanwhile their children had fled to Switzerland.

In December 1943, the elderly couple decided it was time to go. Unfortunately the were arrested not far from the Swiss border at Tirano. They were taken to Tirano prison, then to Como, then to San Vittore prison. There, they were separated. Margherita was sent to the transit camp at Fossoli and Michelangelo being over 70 was released. His freedom did not last long, he was rearrested in Milan on 29 January 1944 and the next day was sent to Binario 21 at Milan Central Station to join the train for Auschwitz. The train arrived at Auschwitz on 6 February 1944, Michelangelo was probably gassed immediately on arrival. Margherita was held at Fossoli until 22 February 1944 when she was sent to Auschwitz, probably being gassed on arrival on 26 February 1944.

The Boehm family home, via de Amicis. The construction is for the new Blue Metro Line

The return of Mussolini

From 16 to 18 December 1944, Mussolini paid a surprise visit to Milan. Leaving the villa Feltrinelli in Gargnano in the late evening he travelled to Milan under cover of darkness to avoid the Allied planes which habitually strafed highway traffic during the day. He arrived at the Prefecture in corso Monforte at around 11, where he was greeted by the Prefect Bassi, after a bowl of clear soup for supper, Mussolini returned to bed.

At 11am the next day, he made a speech at the Teatro Lirico in via Rastrelli. In the afternoon, he went to the nearby piazza San Sepolcro to the Fascist party HQ. Here he made another speech to a large crowd from the balcony. The next day Mussolini travelled in an open car through the streets of Milan. He went to talk to families made homeless in the bombing. He visited the HQ of the Legione Muti in via Rovello and reviewed Fascist militia as they marched down via Dante. On his final day, he attended the swearing in of auxiliary brigades at the Castello Sforzesco. Everywhere he went, he was greeted by large and apparently adulating crowds. From the newsreel footage many of the crowds appear to large and too disorganised to be faking it.

A couple of days after Mussolini had left Milan, Enzo Capitano of the Fronte della Gioventu was betrayed by an informer and arrested again. His former teacher prof. Di Vona at the Liceo Carducci had already been picked up during the summer, he had been shot in the piazza at Inzago on 7 Setember 1944. Ca[itano was taken to San Vittore and handed over to the SS. On 16 January 1945, he was put on a train the transit camp at Bolzano. While the train was passing through Brescia, Enzo managed to throw a note out of an opening in the wagon. It read “To the kind soul, who finds this note, would you do a great favour to a deportee and send it to the Capitano family , via Stradella 13, Milan. Dear Father, dear mother, dear brother and sister, unfortunately I have been sent to a concentration camp”. The note was delivered to his family. A few days later, Enzo was put on a train for Flossenburg. Together with other two other deportees he managed to leap off the train, they then hid out for a few days. Unfortunately they were betrayed. ( As well as angels who delivered messages , there were still some devils out there). Enzo was deported again, this time to Mauthausen. In a particularly cruel blow, he died after the camp had been liberated as a result of the treatment, he had received. He was 18 years old.

Enzo Capitano's family home at via Stradella 13. His last letter to his family was delivered there

January 1945

On 7 January, a bomb killed 14 SS men and Republican militiamen at the Bar Manetti in via Vittor Pisani between the Central Station and Piazza Fiume. The Germans now cracked down hard and anticipated the curfew to 8pm. The remains of Milan’s nightlife were shut down. In January 1945, Giovanni Pesce personally despatched another high-profile member of the regime. Cesare Cesarani was a Colonel in the Legione Muti, he was also the head of personnel at the Caproni aircraft factory ay Taliedo, and as such was responsible for the deportation of numerous workers to German camps. He was known locally as the “beast” of Caproni. Cesarani lived in the east if the city in Piazza Grandi just off the Corso 22 Marzo. He knew, he was under threat- he was escorted everywhere by two bodyguards. But still he was a creature of habit, leaving his apartment most mornings at 7.30 am to walk to nearby Porta Vittoria. Giovanni Pesce was waiting for him. Pesce shouted “Now you have finished sending workers to Germany!” “and shot Cesarani and both his bodyguards. Then he jumped on his bicycle and coolly cycled off while a small early morning crowd applauded.

Milan’s murderous January continued, when on the 12th , the Special Court for the Defence of the State in Milan condemned 9 Partisans from the Fronte della Gioventu to death. Two days later they were taken to an isolated corner of a sports field, the Campo Giurati just outside Politecnico. There they were executed by a firing squad consisting of 24 men from the Legione Arditi di Pubblica Sicurezza "Pietro Caruso” , another autonomous anti- partisan squad reporting to the Ministry of the Interior. The nine men executed were all very young, between 18 and 22 years of age. They had distributed anti-fascist pamphlets and written graffiti in their part of the city, before progressing to the disarming of German soldiers and militiamen and then to more effective forms of sabotage. They were captured by the Battaglione Azzurro , the paratroopers of the ANR, and taken to the Caserma Medici. There the the youths were tortured, but did not give up any useful information. They were taken to the Palazzo di Giustizia ( by this time seeming horribly misnamed) , where they were subject to a sham trial and at the end of each day they were taken back for further torture at the hands of the Battaglione Azzurro, still they refused to talk. Those who were under 18, were allowed to live, the others were sent to their deaths. On a very chilly morning, before daybreak they were shot to death in a quiet corner of the Campo Giurati just behind the grandstand and the athletics track.

The athletics stadium at via Giurati. Near the Politecnico

Memorial to the partisans murdered at via Giurati

On 24 February 1945 Eugenio Curiel’s luck ran out. At around 1500 , he visited the Bar Motta on the corner of corso Vercelli and the piazzale Baracca. He had just gone in, when by sheer bad fortune, two Fascist Militiamen Augusto Pratichizzo and Amilcare Rolando entered the bar. Rolando supplied information to the Germans and worse still, he had been on Ventotene in the early 1940s and recognised Curiel. Curiel was understandably using forged documents and rather than submit these to examination, he shoved the two fascists aside and made a run for it across piazzale Baracca. Either Pratichizzo or Rolando managed to get off two shots from a Beretta pistol hitting Curiel in the leg. He fell to the ground in piazzale Baracca losing his spectacles in the process, finding them he managed to get up and continued his flight across the piazzale towards via Enrico Toti. There two men from the Legione Muti spotted him and fired their machine guns, hitting him in the abdomen. Curiel fell again and managed to crawl to the doorway of via Enrico Toti 4. The two militiamen caught up with him, robbed him of his personal effects and left him to die. They did not even realise that their victim was one of the most wanted resistance leaders in Milan. Passers-by called for an ambulance and a doctor , but there was nothing to be done and Curiel died at the scene,

Milan- April 1945

In the late afternoon of 18 April 1945, Mussolini left Gargnano for the last time. He said goodbye to his family and set off for Milan in a convoy of five cars escorted by SS troops. He arrived at the Prefecture in corso Monforte at around 7pm. Here he was to spend most of his final week in Milan. While he was there he went through the motions of running a government which controlled a rapidly diminishing area. Mussolini had considered making a last stand in Milan and turning it into an Italian Stalingrad. Fortunately for the city and its inhabitants, he decided against this and moved towards the idea of taking the Fascist faithful to a last redoubt in the Valtellina valley North of Sondrio.

Over at the Hotel Regina, the SS officers held a reception for Hitler’s birthday on 20 April, Mussolini sent the Prefect of Milan, Bassi to see if he could find out anything about the German. intentions. The next day the US Fifth Army reached Modena and Regio Emilia was liberated. That evening Mussolini wanted to watch a newsreel film of his triumphant speech at the Teatro Lirico in December the previous year. In the e two days Parma fell to the partisans, the Americans entered La Spezia , the French Army crossed into Italy and the Titoist forces captured the city of Fiume, the Prefect of Piacenza reported that the Germans had abandoned the city, while the Americans has nearly reached Brescia. In a clear sign that matters were ending, the Germans at the Hotel Regina were reported to be burning their records. The only routes out of Milan were to the north towards Lake Como, the Valtellina and Switzerland. The airport was still operating, and on 23 April Claretta Petacci went there to see her family off on to a flight to Spain. Some of his followers urged Mussolini to fly into exile in Spain, others urged him to seek asylum in Switzerland, While the Swiss had indicated that they might grant asylum to the families of Fascist officials and to officials untainted with war crimes, it was highly unlikely that even the Swiss would welcome Mussolini with open arms. The Germans were urging Mussolini head to Merano in German held South Tyrol from where he could cross into Austria. At that time, the only thing secure in Mussolini’s mind was that he was not going to end up a prisoner of the Americans or British.

While Mussolini dithered in the Prefecture, the Germans had literally been negotiating with anybody who would listen in an attempt to save their own skins, Rauff’s superior SS General Karl Wolff had been shuttling backwards and forwards between Bolzano, Lugano and Berne where he had been talking to OSS chief Allen Dulles. Negotiations were now far advanced for a surrender of all German forces in Italy to the Allies. The trouble was that Wolff’s own position was still very insecure, as he was negotiating behind the backs of Himmler and the SS Leadership.

On 24 April , the director of the Banca Commerciale in Milan took a call from colleagues in Genoa advising that an insurrection had started in the city, he told Leo Valiani of the CLNAI , who notified among others Sandro Pertini and they agreed that an insurrectional strike would be called in Milan for 1300 the next day. During the evening heavy fighting broke out between German units and partisans in the Niguarda area, while overnight the partisans attacked German armoured vehicles parked at the Fiera. Aa dawn broke on 25 April, it was clearly going to be an interesting day for Milan.

At 8 am, the Salesian college in via Copernico in the Central Station area , the CLNAI unanimously voted to confirm the scheduled insurrection. As the morning progressed, partisans occupied the Politecnico. By 10 at the barracks and vehicle deport in via Venini, the Germans were hastily loading trucks, especially with Italian tyres and were obviously preparing to leave. Still near the station, in via Fabio Filzi workers at the two Pirelli factories in central Milan jumped the gun and started the strike early. While at the new Pirelli plant in Bicocca partisans overwhelmed the small German guard force. At 1300 the strikes began officially. The Innocenti factory at Lambrate was occupied by partisan units, as was the often-attacked locomotive deport at Greco-Pirelli. Heavy fighting continued at Pirelli in via Filzi, The Germans used an armoured car to batter down the barricades and the defending partisans ran out of ammunition, some of the captured partisans were taken to the nearby Albergo Gallia, perhaps with an eye on the future, the Germans released them unharmed. Meanwhile Mussolini was still holed up in the Prefecture. At 1700 he was taken by car , a purple Isotta Fraschini belonging to a Milanese industrialist to the Archbishop’s place in piazza Fontana where Cardinal Schuster had facilitated a meeting with representatives of the CLN and the RSI. During the meeting. an aide to the Cardinal appeared with the information that Wolff had been conducting negotiations behind Mussolini’s back. The meeting concluded unsuccessfully, strangely Mussolini was allowed to leave the building unharmed. He was lucky that the communist partisan Sandro Pertini, who had sworn to kill him failed to recognise him as they passed on the stairs of the palace. At 7pm Mussolini left Milan for the last time ( while he was still alive) and headed north towards Lake Como. That evening sporadic firefights broke out all over Milan, particularly vicious were the exchanges been partisans and a group of exiled French fascists who were trying to leave the city on viale Zara. Here fighting continued throughout the night until at midnight the French surrendered. That same night, the Pirelli factory in via Filzi changed hands again, this time the partisans took it for good.

On 26 April, the first newspapers in a a “liberated” Milan hit the streets, printed on the requisitioned presses of the Corriere della Sera. Although the partisans were making good progress, the Germans still hung on in strength in various parts of the city . At the Collegio di Martinitt (a large orphanage in Lambrate), at the Casa delle Studente , the Palazzo dell’aeronautica and of course at the Hotel Regina. That morning partisans entered San Vittore prison, where there was a tense stand off as the Germans threatened to shoot prisoners id they came any further. Elsewhere they were more successful , the Germans defending the Palazzo Feltrinelli in via Gaetano Negri agreed not to destroy the Stipel telephone exchange housed there, and Reichsbank officials in the same complex obligingly handed over assets to representatives of the Bank of Italy.In piazza Wagner ,the Feldgendarmarie of the Wehrmacht surrendered without a struggle and the partisans took possession of the Casa di Riposa Giuseppe Verdi. At noon, fighting broke out at the Innocenti factory as the Germans trod to occupy the plant. The partisans counterattacked. By the evening apart from the isolated German outposts , the whole centre of Milan was in partisan hands

The Casa dello Studente and the Palazzo dell'aeronautica. Two of the last strongholds where German and RSI forces held out until 28 April 1945.

On the morning of Friday 27 April units of the Decima Mas attempted to assault the Palazzo di Giustizia and were repulses. In an expression of newfound freedom, a large demonstration turned out in the piazzale Baracca to commemorate the slain partisan leader Eugenio Curiel, at the place where he had been killed. However, the city remained tense and extremely dangerous. That day, an Italian-American OSS official captain Emilio Daddario had taken delivery of Marshal Rudolfo Graziani (the RSI’s minister of Defence) , detained by partisans at Lake Como. On returning to Milan, Daddario judged that the only safe place to keep Graziani for the night was at the SD Headquarters in the Hotel Regina. While there he conducted negotiations with Rauff and stayed the night himself, In fact, by then Rauff was desperately trying to convince everybody that he had been involved at a peripheral level with the “Secret Surrender” negotiations between Wolff and the Americans and was willing only to surrender to the Americans. Absolutely nothing was going to happen to an American officer and his prisoner in the Hotel Regina that night.