The 60th Rifles-A Court Martial in Madras by David Roberts

These days, key board warriors might have referred to Ensign George Gilbert as “snowflake”. Other more reasonable heads might concur, he was being subject to some pretty unreasonable behaviour by his Commanding Officer Lt Colonel Henry Friend Kennedy. Never having been in an army , I can’t really comment on whether Kennedy went too far. Maybe, it is wrong to judge him by today’s standards. I came across this story, since my Great Grandfather’s James Moorcock and Thomas Vaughan happened to be to be in or around Bellary at the time, as other ranks in the 3rd Battalion, 60th Rifles. Hopefully, neither of them messed up Ensign Gilbert’s parade ground manoeuvres, which ultimately led to both men losing their careers. Although both of them , particularly Thomas Vaughan do seem to have been subject to some periods of confinement during their time in India, which might well have been handed down by Lt Colonel Kennedy. The case became a cause celebre in the early 1870s and was even the subject of a book. I leave it to the reader to decide.

The Parade Ground Incident

On 19th September 1870, on a hot and dusty parade ground at Bellary in India, the 3rd Battalion of the 60th Rifles under the command of Colonel Henry Friend Kennedy were conducting a full battalion drill in preparation for a mock-battle intended to be staged a couple of days later. The 3rd Battalion had been in India since 1858, when they had been rushed over a part of the surge of British troops to put down the rebellion. Instead of fighting rebels, they had spent the whole period in the relatively quiet Madras Presidency including a tour oof duty in British Burma,. Any casualties they had suffered in the period had been from disease rather than enemy action.

The 60th Rifles had been at Bellary since 30 December 1867.The town was on a huge granitic mass rising abruptly from the plain, at around 450 feet in altitude.. Compared to some of their previous locations, conditions in Bellary were not actually that bad. The barracks had been improved, as had the sanitary facilities For the officers there was not a huge amount to do, apart from Regimental dinners and Croquet evenings on Saturdays, until a bugle sounded for dinner. Some of the younger officers had taken up cycling around the town. Even the weather was not bad, the summer had ben cooler than usual but with heavy rainfall. The only problem was with some “hooch” from the local bazaar. There had been a number of incidents when men had done half crazy after drinking the local arrack. The Surgeon found out that some of the natives who were licensed to sell alcohol, were rubbing the rims of the glasses with a local plant before serving- It turned out that the plant “Nux Vomica” was actually highly poisonous and when mixed with alcohol was capable of driving mean temporarily crazy. Fortunately the surgeon found that a cure of emetics followed by bland food worked. Despite the alcohol scare, Bellary actually proved to be quite a healthy location. From an average strength of 880, only six men died in 1870, the rate being down to 6.82 per thousand., which was pretty good by the standards of 19th Century India.

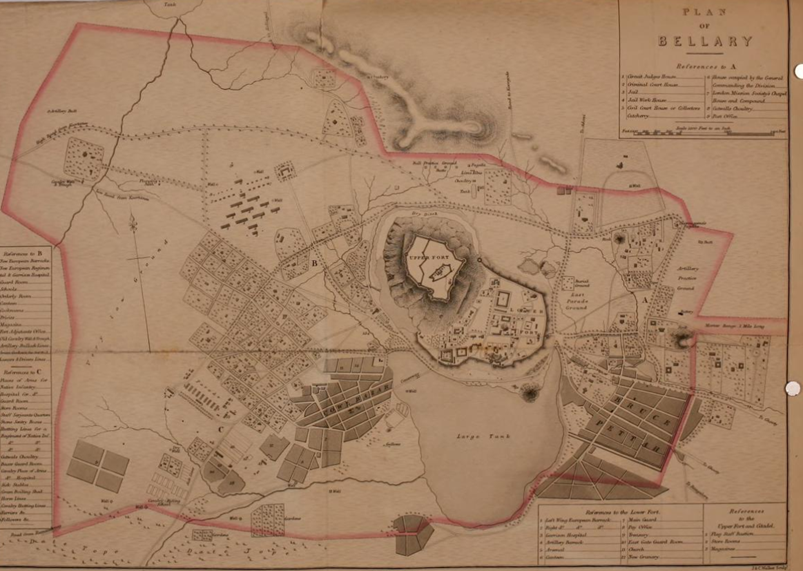

Plan of Bellary in the 1850s. The fortress is on the hill. The British lines and parade ground are to the left

Ensign George Percy Gilbert, the son of a William Alexander Gilbert, a JP and landowner of Cantley Manor, Norfolk. George-s elder brothers Henry Gilbert ( 20th Hussar ) and Walter Edward ( 37th Regiment) had joined the army. Another brother became a vicar. George was educated at Felstead School, Essex and then admitted to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. , aged 16 years and 9 months. He was a fair to medium student; in his final examinations he scored 591 in the obligatory mathematics, 471 in fortifications, 285 in Military Drawing and Surveying, 455 in Miltary History, 460 in French. He finished with a total of 2,078 points, towards the bottom of the class. Whilst not academically gifted, his conduct was exemplary throughout and he received three decorations for merit. He left Sandhurst on 31st December 1866 and purchased his commission on 26th February 1867

Cantley Manor House, Norfolk. Ensign Gilbert's home

Felstead School Essex, Gilbert's old school

On 19 September Gilbert was putting his company through the company drill evolutions. he was carrying out his duties well, if somewhat nervously under the hawk like gaze of Kennedy, unfortunately he was not performing to Kennedy’s satisfaction. Kennedy kept nagging and criticising Ensign Gilbert in front of all assembled- until Gilbert finally snapped and driven beyond the bounds of self-control, threw down his sword and shouted, “I can do no more”. Apparently being a well brought-up young man, that was the limit of Gilbert’s rebellion, he is not recorded to have uttered any profanities and he threw away his sword rather than using it on Kennedy. Nonetheless, Kennedy had Gilbert arrested and marched away under close escort. Gilbert was sent for a Court Martial, an event that was effectively to end the careers of both men.

Gilbert was arraigned on the charge of;

“Insubordination, in having at Bellary , on Sept 19, 1870, at a parade of the battalion under arms . disobeyed the lawful command of Lieut. Col. Henry Friend Kennedy, his superior officer, commanding the parade , by refusing to advance when ordered to don so, saying in a loud voice “No , I will be damned if I do “ , or words to that effect; at the same time throwing his sword violently away."

The Court Martial

Ensign Gilbert’s Court Martial commenced on 1st November 1870, in the Court Martial Room of the Main Guard House at Fort St George, Madras. The Court Martial presented a microcosm of British Queen Victoria’s “Small wars” up until 1870. Members of the Court Martial and witnesses had served in places as far flung as Jamaica, Uruguay, South Africa, Abyssinia, Burma, China, Ireland, the Crimea, Canada ,and in India from the Sikh Wars to the Rebellion. In between they had partaken in the odd spell of putting down Chartists and “pro-democracy” movements in the United Kingdom. This brotherhood of officers whose paths had crossed or nearly crossed in various parts of the world assembled in Madras to ponder on the fate of Ensign Gilbert.

A view of Fort St George, British seat of Power in Madras

The President of the Court Martial was Lieutenant- Colonel Henry Woodbine Parish, Commanding Officer of the 45th (Nottinghamshire) Regiment (The Sherwood Foresters)., a distinguished officer who had served with the 45th Regiment at Montevideo in 1845, then in the Wars of 1846- 1847 and 1851-1852 in South Africa. He had commanded the 45th Regiment during the Abyssinian Campaign of 1868 and had been present at the storming of Magdala for which he had been made a CB and had been mentioned in despatches.

The other members of the Court Martial consisted of officers drawn from the Madras Staff Corps or officers serving with Regiments stationed in Madras and included:

Major William Barclay Madras Staff Corps

Major G Kalllender Madras Staff Corps

Captain RC Stewart 8th Madras Cavalry

Captain J Lampen 17th Madras Native Infantry

Captain GS Keith 35th Madras Native Infantry

Captain Jennings 3rd (Madras) Light Infantry

Captain C D Straker Royal Artillery

Lieut. W B Cooke Royal Artillery

Lieut. J Maunsell 16th Lancers

Lieut. F J Lawder 17th Madras Native Infantry

As a President, the Court could not have wished for a more experienced officer than Parish, His career alone, illustrates just how far and wide the British Army had travelled in the first half of the 19th Century.

To the right of Parish, sat Colonel George Frederick Shakespear, Deputy Judge Advocate of the Southern Division. Shakespear, a distant descendant of the playwright, was the son of William Oliver Shakespear a Judge in the Provincial Court of Appeal of the Madras Presidency, who had purchased his commission in the 26th Madras Native Infantry and had been present at the capture of Badamee in the Southern Mahratta 1841 He had also served in the second Burma War.

A General Court Martial required the presence of the Judge Advocate General, a Judge Advocate or Deputy Judge Advocate deputed for the purpose. The aim of the Court was Justice and Shakespear’s responsibility was to see that justice was done and that all the enquiries and attention of the Court were directed to that end. He was responsible for the accommodation of the Court, for summoning the witnesses and for registering all the proceedings of the Court and recording all the oral evidence as near as possible in the actual words of the witnesses. He also advised the Court on points of law and custom. The parties of the Court had the right to his opinion on any questions of law. He was especially obliged to make sure that the Prisoner, Gilbert, did not suffer from any want of knowledge or experience in eliciting replies from the witnesses and developing his defence.

Lt Colonel Kennedy sat at the far end of the table. By the custom of service, the duties of the Prosecutor devolved on the person who originated the charges or the Prisoner’s Commanding Officer, which in both cases happened to be Kennedy.

Gilbert sat at another table with his legal adviser, Mr Michael Gould, from Cork in Ireland, a Madras Barrister at Law. Only the parties to the case were allowed to address the Court, it being accepted practice that Counsel were not to interfere in the proceedings or to plead or argue before the Court. Gould’s presence was therefore tolerated in his capacity of “friend of the prisoner” and his role was strictly limited to assisting Gilbert by shaping the defence, providing advice , taking notes and preparing the questions which Gilbert would put to the witnesses.

Another view of Fort St George

The proceedings started at 11am prompt, with Colonel Shakespear, reading various orders on the conduct of the Court Martial and swearing in the members. Parish then asked Gilbert, whether he objected to any members of the Court, which he did not. However, Kennedy did raise an objection, but was told that the Prosecutor could not do so.

Kennedy was in the somewhat unusual position of being Prosecutor and Chief Prosecution witness, so rather than make an opening statement as Prosecutor, he submitted himself as the first witness.

In his statement Kennedy recounted his version of the events of the previous 19th September. By 1870, Kennedy had been serving with the King’s Royal Rifles for close to thirty years and had seen service in Jamaica, Canada and India. In December 1841, he had sailed to Jamaica with the 60th Rifles.. For Kennedy, the posting to Jamaica was a return to his maternal roots. Kennedy’s mother Maria Pinnock was from a longstanding Jamaican settlor family. In 1816, Maria had married a Naval Lieutenant, Andrew Kennedy. Andrew Kennedy had entered the Navy in 1808 as a Midshipman where he had served on HMS Penelope at Martinique. After Henry’s birth in 1824, Andrew Kennedy had been away serving on the West Indian and North American stations and in 1838 had gained a certain note in taking the first British man-of.-war up the Orinoco River. By 1841, he was more or less on the retired list.

Kennedy had purchased the rank of 2nd Lieutenant in the Rifles on 11th September 1840. In the 1840s entry as an Army Officer was either “by purchase” or “without purchase”. By far the greater proportions were “by purchase”. For infantry Regiments application was made through some known and respectable individual, such as a magistrate, clergyman or country gentleman to the Military Secretary to the Commander in Chief for entry by purchase. The character and personal qualifications of the candidates were enquired into, their names were kept on a list held by the Military Secretary, and as vacancies occurred candidates were selected to fill them. Since the list generally contained about 2,000 to 3,000 names only a small proportion of candidates were accepted. Each candidate, when selected, received a memorandum of the educational subjects upon which they would be examined and those who passed creditably were appointed on the payment of the purchase price of £450. The vacancies to which purchasing candidates succeeded were often made by the retirements of senior officers who sold their commissions downwards. In Kennedy’s case he purchased from 2nd Lieutenant Bateson who was promoted to Lieutenant, the regulation price being £450.

As a new Subaltern, of 18 years old Kennedy was in charge of men of greater age and experience and therefore the key was to work on mildness, patience, and good temper with the soldiers. The other ranks were men of many years' experience: many of them soldiers with high feelings of pride and honour; and he would need to take particular care that what he might deem o be ignorance or lack of intelligence in these men, might in fact stem from his own insufficiency. For two years after a Subaltern first joined, he was generally required to attend all Courts of Inquiry and Courts-Martial held in the Regiment, to learn the manner in which they were conducted. The new Subaltern had to make himself acquainted with the Mutiny Act and Articles of War; the Standing Orders, General and Regimental; and always keep in his possession the books named in the Orders. Generally a minimum of two years was required before a Subaltern could take charge of a company

On 11th April 1842, Kennedy was fortunate to be promoted to Lieutenant, without purchase in place of Sir Ross Mahon, Bart. The unfortunate Sir Ross Mahon was found dead in his bed after a Vice regal dinner party at Dublin Castle. Despite the fact that Mahon had died in Dublin and Kennedy was in Jamaica, he got the promotion anyway. Lieutenant Kennedy and the new arrivals from the 2nd Battalion encamped at the Newcastle Estate Government Plantation at around 4,000 feet above sea-level thus avoiding the worst of the yellow fever ravaging the coast.. In January December 1841, the 60th Rifles were called to support of the Civil Power in Jamaica, when Christmas and New Year celebrations. Got out of hand and turned to rioting. On 28th December 1841, 300 men of the battalion marched down from Newcastle to Up Park Camp in readiness to provide assistance to the Civil Power in quelling the disturbances. The riot at length reached so great a height, that the police, feeling themselves to be in the most imminent danger, fired on the people. Two individuals were killed on the spot, two later died, and a considerable number were wounded. It then became necessary to call out the troops. On 23rd December 1842, a still larger contingent of the 60th Rifles again marched down to Up Park Camp to assist the Civil Power in putting down further disturbances. By all accounts the 60th Rifles seem to have acted with considerable restraint. Not a single shot was fired nor a single life lost after the first shootings by the police took place and tranquillity was restored to Kingston.

There was further excitement on 26th August 1843, when fire broke out in Kingston and the battalion went down from Newcastle to assist in the firefighting.. A huge conflagration ripped through Kingston By 3 o’clock there were no less than 10 fires raging in widely separated areas each involving 3 or 4 houses at a time. The 60th Rifles commenced their march down from Newcastle to assist in the securing of private property. The engineers, with their artillery and guns, being also utilised in the destruction of many buildings which lay in the path of the flames. The fire raged for sixteen hours and over 30 city blocks were completely demolished either by fire or by deliberate destruction in an attempt to stop its progress. The General Officer Commanding Major-General Berkeley congratulated the 60th Rifles on the speed with which it had arrived and helped to save the city from conflagration. A few days after the fire the battalion returned once again to Newcastle.

In January 1844, after this spell of putting down civil disturbances and fires Kennedy returned to the depot in England. In February 1845, he re-joined the service companies of the battalion, which by now had moved from Jamaica to the Citadel Barracks in Quebec. In May 1845, the Battalion moved again to St John’s, Nova Scotia. Kennedy was not in Canada long; on 5t August 1845 he exchanged into the 1st Battalion and sailed for home again. When he arrived, the 1st Battalion had already departed for India, where problems were looming in the Punjab. Although the Sikh Army had been defeated in December 1845, the British had suffered substantial losses and a reduced British force was having difficulty holdings its ground and was in need of reinforcement. In February 1846, the Rifles moved to Karachi in readiness for operations and it was here in April 1846, that Kennedy finally joined his new battalion. On 20th October 1846, Lt Colonel George Currie Page , unattached to any regiment , retired and cashed in his commission. This opened up a vacancy and a line of officers waiting below moved up a step. Kennedy purchased the step up to the rank of Captain in his place. Although, he had made Captain in five years, Kennedy’s next promotions were to take rather longer to achieve

In 1848, trouble flared up in the province of Mooltan, which had been under British rule for only two years. The 60th Rifles with Captain Kennedy among them marched out of Karachi on 7th October 1848 for Tatta, where they embarked on steamers of the Indus Flotilla to join the Bombay division at Roree. On 23rd November, the 60th Rifles began its march towards Mooltan, crossing the river Sutlej by a bridge of boats. On 7th August 1855, Henry Friend Kennedy purchased the step up to Major in the 3rd Battalion and left for India on 23rd November 1857.

On the 2nd day of the Court, Gilbert was unwell, Dr Fennimore the Medical officer of the 45th Regiment certified that he was “ill in bed with a severe fever” and the Court was adjourned. Proceedings were resumed on 12th November, when Gilbert continued his cross-examination of Kennedy.

On the 14th November, Colour Sergeant William Lynch was called to give evidence. Under cross examination by Gilbert, when asked whether Kennedy was habitually harsher or more severer with Gilbert, than with other officers, Lynch replied;

“I have heard Colonel Kennedy in several instances address Ensign Gilbert in what I thought was harsh language. I have heard the Colonel speak in as harsh a tone to other officers as he has to Ensign Gilbert”

Lynch also confirmed that it was not unknown for Kennedy to remove officers from their Companies for alleged incompetence and for the command to be given to Non-Commissioned Officers. The next day he was re-examined by Kennedy , who asked him to recount the times and dates when he had heard him speaking harshly to Gilbert. Lynch recalled that the first occasion had been in Madras in 1868 and that there had been other instances between then and September 1870.

Next to be called as a witness, was Captain Borthwick who had been commanding one of the other Companies during the manoeuvres. Borthwick recounted a conversation where Gilbert had complained that nothing he could do appeared to satisfy Colonel Kennedy. Later, Borthwick agreed under examination by Gilbert, that he too had been subjected to “harsh and irritating conduct “ by Colonel Kennedy on several occasions. He was then re-examined by Kennedy.

When it reconvened on 17th November, the Court put a direct question to Borthwick as to whether Kennedy had communicated with him between the 19th September and the Court Martial. Borthwick confirmed that he had not. Responding to another question from the Court, he said that he had known Gilbert for about four years and that “his ability is decidedly above the average and his conduct has been uniformly zealous and good.”

Gilbert, then began to call witnesses for the defence. First to be called was Lieutenant Benjamin Frend. Frend had been in India since September 1866, he had been a Gentleman Cadet at the Royal Military College, purchasing his commission on 9 February 1864. Frend testified on his recollections of the manoeuvres. He also confirmed that in the past Colonel Kennedy had removed him from the command of his company, and made him follow in the rear while it was commanded by a more junior officer. Next to be called was Lieutenant Henry Blackwood McCall, who had also been on the fateful parade. McCall testified that Lt Colonel Kennedy gave his commands in such quick succession , that it is impossible to say the number he gave in one minute and that he gave Gilbert no time to obey his commands. He agreed that Kennedy’s commands and manner were “confusing” and “very probably” calculated to make Gilbert lose his presence of mind. He also testified that ; “ Barring myself, I have observed Colonel Kennedy’s more overbearing manner to Ensign Gilbert, than to any other officer, since I have been in the battalion , over three years.” McCall was therefore not surprised that Gilbert had lost control that morning. He added that Colonel Kennedy was in the habit of singling out an officer on parade to bully more than another when officers had been away on the leave from the battalion for any length of time. “As Ensign Gilbert had been away I thought that in all probability, he would be pitched into more than any one else that morning.”

On 21st November, Ensign Charles Radley Brittain Thorne was examined. He had been present at the parade as subaltern of Captain Borthwick’s Company. Thorne testified to one occasion when he had been instructed to take-over Gilbert’s company from him , as Gilbert’s junior in the service. Thorne also recalled that on one occasion his own company had been taken from him and given over to Colour Sergeant Lynch. Thorne also testified to the aggravating tone of the commands used by Kennedy.

Next to testify was Ensign Harry Willis Sandford. His testimony was very similar. He recalled the incident where he, as a junior officer had been ordered to take over Gilbert’s company. He also recalled a similar incident where Kennedy had ordered Ensign Featherstonehaugh to take over his company and a further incident where he had made two mistakes on parade and he his company was taken from him and given over to Sergeant Lynch, with him falling into the subaltern’s place under the Sergeant’s command.

Sergeant Edward Jenkinson, Bandmaster James Coleman and Private Welbrook then gave testimony on various aspects of the incident. Coleman testified that he had heard Kennedy utter the phrase “you are not fit Sir to command a company “- but that he was not sure at whom that had been directed. Private Welbrook recalled that he was the private to whom Gilbert had asked the number of the company

On 23rd November it was the turn of Captain Algar to give evidence. He had been acting Junior Major on the morning in question. He recalled giving an order to Ensign Gilbert to “dress up “ the right of his company , but before Gilbert had a chance to obey he had been ordered to take command of the company , with Kennedy saying “He cannot command it “ or “He is not fit”- he could not remember exactly which.

Major Hugh Parker Montgomery was next to be examined. He had commanded the three companies skirmishing in the front-line of the parade. Montgomery had a long history with the 60th Rifles and must have been a credible and formidable witness. A distant ancestor had gone over to Ireland in the early years of James 1st, married a Stewart heiress and laid the start for the Montgomery family fortunes. Later members of the Montgomery family had continued to marry well, building up substantial estates in the North of Ireland, finally purchasing the estate of Grey Abbey. h In 1831, Arthur Hill Montgomery purchased Tyrella House in County Down, which became the family home. Hugh grew up in this charming Georgian House, overlooking out over the bay of Dundrum with the Mountains of Mourne in the background, before going onn to Eton and the &0th Rifles.

Montgomery who had recently joined the 3rd Battalion after serving with the 2nd Battalion for many years gave some interesting insights during his examination and cross-examination. Asked by Gilbert whether it was in accordance with the custom of the service for Commanding Officers to take command of companies from officers and give them to Sergeants , Montgomery replied that he had never seen it done until he joined the 3/60th. He concluded that he “long thought that Colonel Kennedy’s manner would be likely to cause a breach of discipline in the Regiment.”

During his examination there followed a fairly tense exchange between Kennedy and Montgomery. Kennedy asked Montgomery whether as the officer next senior to him, and as second in command he had ever reported to him the discontented feeling of officers or soldiers regarding his conduct. Montgomery replied that he did “not think it would be within the bounds of discipline for me to find fault with my Commanding Officer’s conduct.”

Next it was the turn of Captain Cromer Ashburnham to give evidence. Under examination by Gilbert, Ashburnham confirmed that he had known Gilbert for more than three years he had been his subaltern and later when he had commanded a company in the wing of which Ashburnham was acting Field Officer. Prior to September 1870, Gilbert had also served under Ashburnham’s immediate command at the convalescent depot at Ramandroog. Ashburnham a long- standing officer and veteran of putting down the Rebellion, testified that he had always found Ensign Gilbert “a most pains taking, hard-working , willing and obedient young officer , zealous in the performance of his duties , fond of his profession, and most anxious on all occasions to give satisfaction to his superiors. His conduct and bearing have always been that of a perfect gentleman.”

Ashburnham went on to recall that Ensign Gilbert had been removed from his company on Colonel Kennedy’s instructions and that Kennedy had told him that he “spoilt Ensign Gilbert and that I was too kind to him”. He also recollected that Gilbert had frequently complained to him of his treatment at the hands of Colonel Kennedy, one morning Gilbert had come to him almost sobbing that he no matter what he did for Kennedy it was not right . Ashburnham remembered that he had replied ;” It is no use making a row , Colonel Kennedy is always pitching into somebody . I am pitched into as much as anybody else, but I don’t take the slightest notice of what hew says” In a further conversation which took place between them in Ramandroog , Gilbert was worried about Colonel Kennedy’s attitude to him when returned from convalescence, and that he attributed his sickness entirely to Colonel Kennedy’s bullying, keeping him on long parades in the heat of the day and then having to attend the orderly room for long periods. On their parting, Ashburnham had told Gilbert “take care of yourself; you are certain to be pitched into on your return , but whatever happens don’t lose your temper on parade”.

Ashburnham was then examined by Kennedy particularly on the subject of language used. He admitted that:

“Colonel Kennedy uses less coarse language than any Commanding Officer I have served under I think , but his manner is very irritating, very aggravating and at times intensely provoking and offensive”. Following an adjournment for tiffin, it was the turn of Lt Colonel Peter Burton Roe. Roe confirmed that he had commanded the 3rd Battalion from February 1862 to March 1867 and again from November 1868 to November 1869, before quitting the battalion to become Adjutant General of the Army in Madras. Roe was the scion of a wealthy Dublin family with substantial interest in Gin distilling. He purchased his commission in the 2nd Battalion on 23 July 1841 after graduating from Dublin’s Trinity College and had arrived in Canada in March 1844. Similarly to Ashburnham, Roe gave his view of Gilbert “as one of the most intelligent and zealous officers in the battalion. I never heard any question of his conduct as a gentleman . I never had any occasion to find fault with him on any subject. Perhaps not surprisingly, Kennedy chose not to cross-examine his former commanding officer and Regimental Surgeon Adam Young was sworn in.

He testified that on 17th March 1870 in Bellary, Gilbert had suffered a bad attack of fever and congestion of the brain brought on by exposure to a hot morning sun during an unusually long period of drill. He had then been sent on a two month’s medical ertificate to the sanatorium at Ramandroog. Whilst there on sick certificate Gilbert had been ordered to report to the Commandant to do duty with the depot.

Young was another highly credible witness, On 13th November 1854, Assistant Surgeon Adam Graham Young arrived in the Crimea, where he was to be attached to the 2nd Battalion, Rifle Brigade, Young had provided medical assistance throughout the Crimean War before subsequently joining the60th Rifles on South Africa and India. Kennedy cross-examined Young on the reasons for Gilbert falling ill after a parade in Madras in 1867-, which Young had attributed to an overlong recruit drill. Kennedy put forward an alternative view that Gilbert had been in the habit of taking carriage rides and bicycling without protection from the sun.

On 2nd December , the 16th day of the proceedings, Gilbert was ready to make his defence. With the court’s permission this was read out for him by a Colonel Campbell of the Royal Artillery.

Gilbert’s statement started by apologising to the Court that he had found it necessary to ask so many questions questioning the conduct of his Commanding Officer- but that this had been necessary in the interests of self-defence. He asked the Court to consider firstly whether he had been guilty of insubordination and to put aside the flinging away of his sword and the words he was alleged to have spoken. Any words he said had no precise meaning other than a violent and almost unconscious assertion of his own inability to do more than he already had in obeying the Colonel’s orders.

He then turned to examine the order he was charged with disobeying. The original order was “To advance or quick march to the place wherein to dress my company”- all other orders such as “advance” or “quick march” had to be referred back to that original order. Gilbert’s Statement then went through a forensic analysis of the evidence given;

1. Kennedy said he had given the order to advance in direct echelon. Borthwick, Frend, MacCall and Thorne had all deposed to the fact that he ordered advance in short echelon.

2. Kennedy asserted that Borthwick could not dress his company because Gilbert’s company was in the way. Borthwick said that he was not in the way- but that he was unable to dress his company, because of Kennedy’s own actions

3. Kennedy alleged that Gilbert had thrown away his scabbard and waistband after being paced under escort- this was contradicted by Sergeant Lynch who said it was before.

4. Kennedy said he had recalled the escort after about a hundred yards- contradicted by Thorne and Thurlow and corroborated by Algar

5. Kennedy denied having said to Gilbert “You are not fit, Sir, to command a company. Captain Algar, Sergeant Jenkinson, Lieutenant Frend and Bandmaster Coleman all recalled hearing the phrase.

6. Kennedy denied having taken the command of Gilbert’s Company that morning- - this was directly contradicted by Captain Algar who had temporarily taken over the company.

7. Colonel Kennedy said that he had wheeled back round to the right of Borthwick’s company and ordered other companies to conform with the movement. However, it was clear from the evidence of Borthwick, Frend and Algar that no such order had been give.

8. Kennedy had denied telling Gilbert to ask a private for the number of his company in an ordinary tone- this was contradicted by Private Wellbrook but also on the question of the tone of the order by Borthwick and Frend.

9. Again Kennedy had denied in the past removing Gilbert from his company and putting him under the orders of a junior officer – this was backed up by the testimonies of Ensigns Thorne and Sandford and also the experiences of Lieutenant Frend.

10. Kennedy’s strangest delusion was that he had used a measured tone throughout. All the evidence contradicted this and he was variously described as using a tone which was “aggravating”, “harsh and aggravating”, “loud and excited” and loud and bullying”.

All of this was enough to establish Colonel Kennedy’s testimony as unreliable and that there was conclusive evidence in the testimony from Sergeant Jenkinson and Captain Borthwick that Gilbert had moved his Company to almost the right place and the order had been obeyed.

In his closing address Kennedy as Prosecutor attempted to prove the legitimacy of the charge of insubordination and then to refute some of the allegations which had been made about his own conduct and character.

On Saturday 10th December Colonel Shakespear , gave his summing up:

“ It now becomes my duty to sum up the evidence in this case, which I will endeavour to do as briefly a possible. The prisoner is charged with insubordination in having at Bellary , on the 19th September 1870 disobeyed the lawful order of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Friend Kennedy , his superior Officer , Commanding the parade, by refusing to advance when ordered to do so, saying in a loud voice, “No I’ll be damned if I do” or words to that effect, at the same time throwing his sword violently away.

The prisoner in his address has stated that the words alleged to have been spoken , and the act of throwing away his sword , should have no weight with the Court in their finding as to his guilt or innocence , but i would submit to the Court whether they can reasonably exclude these matters from their consideration in determining whether the prisoner is, or is not, guilty of the charge of “ disobedience of lawful command under the 38th Article of War . The question which the Court will have to decide is whether a lawful command was given, and whether the prisoner did , or did not disobey that command, without reference to any amount of obedience that may have been rendered by him previous to the command referred to. “Shakespear then ran through some of the evidence given by the prosecution particularly by Colour Sergeant Lynch and Captain Borthwick. He then wrapped up by describing Gilbert’s state of mind when the offence took place.

“Evidence has been adduced on the defence to show that on the morning of the 19th September , Colonel Kennedy’s tone and manner were “harsh and aggravating”, “ most excited and aggravating”, “very aggravating and overbearing” , “ most irritating” , “ loud and bullying”, “bewildering”, “confusing” , and the prisoner has told you that it was owing to the treatment and provocation he received that he lost his self-control that morning. His conduct as an officer and a gentleman, as the Court are aware , have been spoken to by several gentleman , as the Court are aware , have been unexceptionable up to the time of this unfortunate occurrence. These circumstances , however if established to the satisfaction of the Court, would go to extenuate the offence – not to disprove the charge, and if the Court consider them established , they, of course, can give them such weight , as they think proper ,in estimating the gravity , or degree of the offence , but the charge being one which rests upon a fact, and not on a mere imputation , the Court, in coming to their finding , should first determine according to the evidence before them whether the fact has been proved , or not, and find accordingly”

Throughout the case there was a great groundswell of sympathy for Gilbert, he was visited every day of his Court Martial by Colonel Roe who was based in Madras and who continued to maintain an interest in one of his protégés. The case even got a mention in the Times whose Indian Law Correspondent said:

“The finding of the Court is not yet published, but may I say that the evidence has evoked a good deal of sympathy in the army and out of it for the ensign, and a good deal of something reverse of sympathy for the commanding officer. There can be little doubt that Ensign Gilbert must quit the army but he certainly seems to have great provocation before the final explosion on parade”

Lord Napier of Magdala

In the end the Court Martial found Gilbert guilty and he was cashiered from the Army. Lord Napier of Magdala confirmed the sentence.

“The court have found Ensign Gilbert guilty of an act of the gravest insubordination, committed on parade.. in front of the men under his immediate command, and gave sentenced him to be cashiered, but have earnestly recommended him to mercy on the ground of the extreme provocation from his commanding officer” and on his previous high character. It is with great pain that I fund myself unable to yield to this earnest recommendation. Acts of insubordination have prevailed in the army during the last two years, to an extent which threatened , if unchecked to impair seriously all regimental authority; in some cases provocation has been urged as an excuse, and it has been necessary to show , by the certainty of punishment ,that mothing can palliate insubordination. It is nowhere shown that Ensign Gilbert sought the means provided by the Articles of War for obtaining protection from his commanding officer. The interests of discipline, on which the welfare of the army depends, forbid my condoning Ensign gilbert’s offence, and thuis converting it into a dangerous example. “

Notwithstanding the general sympathy for Gilbert, a report was submitted to Horse Guards and His Royal Highness, the Commander in Chief chose not to exercise the Royal Prerogative. Despite all the provocation Gilbert had still been guilty of insubordination and he was cashiered from the Army on 19th April 1871.

The case proved equally damaging for Kennedy, the testimony of his brother officers of the status of Montgomery and Ashburnham had placed a stain on his character and drawn into question his fitness to command. Following the Court Martial of Ensign Gilbert, Colonel Kennedy was removed from his command of the 3rd Battalion by Lord Napier,. Clearly the Court Martial had been a contributing factor, but the immediate reason seems to have been a further incident in which Colonel Kennedy ordered the arrest of a certain Ensign Michell who had expressed some sympathy with Gilbert’s plight.

George Percy Gilbert seems to have returned to Norfolk, at least the 1871 census, has him living back with the family at Cantley Manor , Norfolk – still described as an “officer 60th Rifles. George Gilbert seems to have ended up in the USA for a while. The 1879, Armorial Families records “George Percy Gilbert , late 60th Rifles b .1849: m 1st 1876, Agnes , d of John Lynes of Virginia , USA. By 1891 Census he was back in England, at Weston Super Mare – described as “living on his own means”. He died in Bath in March 1912.

George Percy Gilbert eventually retired to Weston Super Mare

Having been removed from his command , Kennedy was replaced by the ever-popular Major Montgomery, who accompanied the 60th Rifles to Aden for a year and then back to England. Kennedy also returned to England, he retired on full pay in 1872 and was given the honorary rank of Major General. In 1881 he was living in Bath. Where he died in 1893

Clearly Ensign Gilbert was guilty of disobeying an order, he did not deny that-the main arguments seem to be was to whether there was any mitigation for his actions. The court believed no and the Army had to make an example of him . From the evidence Kennedy does seem to have bee a bit a difficult character. Maybe, he had his reasons , it had taken him years to get to where he was ad in the 2purchase” system, he was being jumped over by less experienced, but wealthier officers. We are not in a position to judge his motivations.