April 25- Liberation Day/ ANZAC Day on the Milan Escape Route

Continuing my trip around Lake Maggiore, this time on the opposite side from Meina and Baveno still in Italy, but in Lombardy between Caldè and Luino. Once again, we are on the track of escaping fugitives from the Nazi-Fascist occupation of northern Italy. Due to their proximity of the Swiss border, during World War Two Caldè and Luino were staging posts for not only escaped Allied Prisoners and other fugitives from Nazi/Fascist tyranny before they tried to cross the border. Many of the prisoners were Australians and New Zealanders who had walked out of the workcamps in the Vercelli area following the Italian Armistice on 8 September 1943. They were helped by a remarkably brave collection of Italians who formed part of an escape network organised by Giuseppe Bacciagaluppi, together with an Italian Priest and another escaped Australian Prisoner. Today, the towns on Lake Maggiore are peaceful and prosperous, in 1943 they were occupied by the Nazis and places of fear. Fear, but also the hope of making it across the border to safety. Since 25 April is celebrated both as Liberation Day in Italy and ANZAC day, it seemed appropriate to commemorate both the Italian and Australian participants in those dangerous times.

The town of Caldè on Lago Maggiore , a staging point on the Milan Escape Route

First stop is Caldè where Giuseppe Bacciagaluppi had his home. Bacciagaluppi was born in Milan on 10 June 1905 , into a highly cultured and antifascist family , he gained his high school diploma at the Liceo Valdese at Torre Pellice in Piemonte and then graduated in electronic engineering from the prestigious Politecnico di Milano. In December 1930 he married a British woman, Audrey Partridge Smith, and moved to Zurich for work. Back in Italy he was hired as an engineer in the telephone factory of FACE Standard,rapidly becoming a Senior Executive in the firm. Giuseppe and Audrey had a home in Caldè , a small resort on the Lombardy side of Lake Maggiore, around 30km from the Swiss border and on the railway line from Gallarate to Cadenazzo in Switzerland. These days the trains start in Gallarate and most of them terminate in Luino. In 1943, there were Italian steam trains train on this line, these days they are sleek and modern electric trains operate the Italian Swiss joint venture TILO. Caldè is an attractive little village . with some fine lakeside views but otherwise there really is not much there. Since seeing Caldè probably takes only a quarter of an hour you either wait for two hours for the next train or find the footpath out. Although somewhat cleverly concealed and not signposted there is a footpath from Caldè to Porto Valtravaglia, the next town on the lakeside.

The small harbour at Caldè

The streets of Caldè

This another sleepy little town with some stunning lakeside views and not much else going on. The path from Caldè emerges in a rural fraction above Porto Valtravaglia and a road leads down past the station to the lakeside. Opposite the station is the former barracks, which provides another reminder of the difficult times around the Italian Armistice.

The former barracks at Porto Valtravaglia

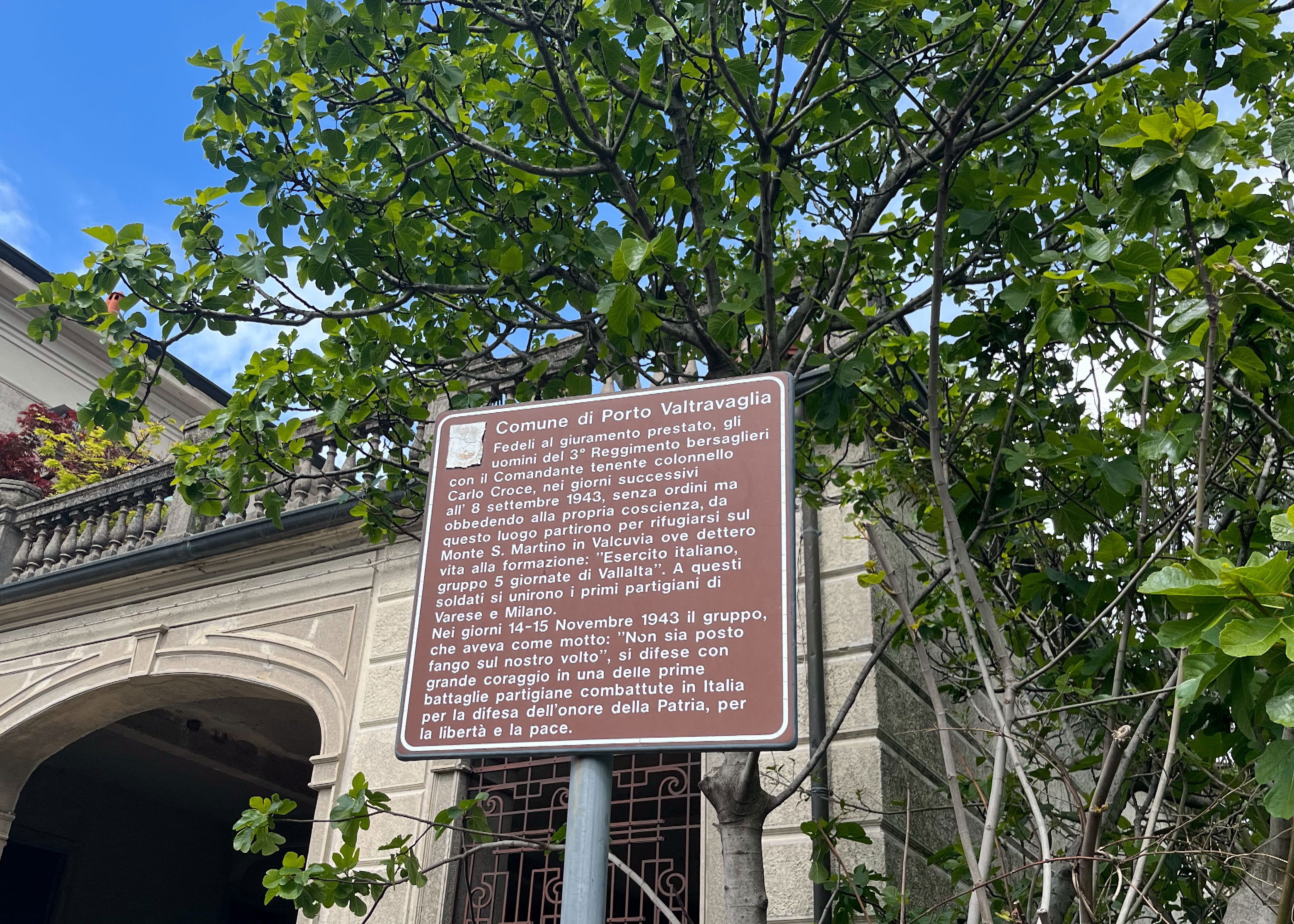

Memorial for colonello Carlo Croce at Valtravaglia

On 8 September 1943, colonello Carlo Croce was commanding a detachment of the third Bersaglieri regiment at Porto Valtravaglia, the unit was made up of two battalions, including airmen from the Regia Aeronautica still to be trained. For the first few days following the armistice they remained around the commander. The unit was left without orders and Croce realize that Badoglio’s proclamation opened the doors to the occupation of Italy by the Germans, As a veteran of the Italian expeditionary Force in Russia, Croce had already witnessed what the German occupiers were potentially capable of. As events worsened ,Croce then decided to move to the abandoned fortifications of the Northern Frontier near Cascina Fiorini. Since his small garrison had no weapons or ammunition available, Croce had to procure them from the barracks in nearby Luino and Laveno, or from disbanded soldiers who were trying to take refuge in Switzerland. What he could obtain was transferred to the headquarters in the former "Luigi Cadorna" barracks in Vallalta di San Martino on requisitioned military trucks and civilian vehicles. His unit was formally named Italian Army-Military Group "Cinque Giornate" Monte San Martino di Vallalta Varese.

Meantime, many of the conscript soldiers had headed for home or for Switzerland (at a certain point leaving Croce with only ten comrades); however, his formation was replenished by other former soldiers and civilians intent on taking up arms against the Germans: until he had around 170 men at his disposal . Initially, the actions of the "Cinque Giornate" group were limited to the strengthening of their defensive positions, the digging of ditches and trenches, the "surges" downstream for the supply of food (sometimes even scarcer than ammunition) and the surveillance of the nearby streets, which converged right in the square in front of the former barracks in Vallalta. Croce organized the formation as a real department of the Royal Army, having in mind a "wait-and-see" line and not a guerrilla war. The attempt by a representative of the CLNAI to convince Croce to divide his men into groups of smaller size, but more agile and suitable for guerrilla warfare, which would have prolonged the survival of the formation while also increasing its effectiveness, was of no avail. Furthermore, the lack of secrecy that characterized the unit (there were no "battle names" but even military identity cards complete with photographs) made it easy for the enemy to infiltrate, so it was not difficult for the Germans and fascists to gather information on the unit's weak points. For the first few weeks the "cinque giornate" did not seem to worry the Germans too much, but as winter advanced it was feared that they could constitute an obstacle in the control of the territory, Of course, the Germans were also preoccupied that the partisans would damage or destroy that vital railway link along Lake Maggiore to the Swiss border. so on 13 November a “state of siege” was proclaimed and the following day all the men aged between 15 and 65 were rounded up from the local villages located and locked up in public buildings or churches. On 15 November, Colonel Croce and his men began to resist the arrival of enemy patrols, blocking the roads to Mesenzana, Arcumeggia and Duno. That same day the Luftwaffe attacked his positions perched on the mountain with a very heavy bombardment. The unit was then besieged by a force of some 3,000 Germans, although heavily outnumbered Croce’s men fought back valiantly , destroying German armoured vehicles and even downing a German plane. However, the situation was clearly hopeless and the remains of Croce’s group fled towards Switzerland, which they reached at dawn the following day. Croce did not remain in the safety of Switzerland, he returned to Italy to continue the fight . He was severely wounded and captured in a firefight in the alps above Sondrio. After being tortured by the SS, he died on 24 July 1944 at a military hospital in Bergamo.

After the Armistice of 8 September, Bacciagaluppi made contact with a unit of the Italian Army on Monte Cuvignone convincing them to head towards Switzerland and be interned. Thanks to his friendship with Ermanno Bartellini ( a militant anti-Fascist who was later murdered in Dachau in 1945), Bacciagaluppi was introduced to Ferruccio Parri, who at the time was working for the electric company Edison in Foro Bonaparte. .Parri had long been active against the Fascist regime and joined Carlo and Nello Rosselli's Giustizia e Liberta. In 1926, together with Carlo Rosselli and future President of Italy Sandro Pertini . Parri had been involved in planning and assisting the escape to France of reformist Socialist leader Filippo Turati. Parri was arrested and sentenced to ten months of imprisonment and then to five years of confino (internal exile) to the islands of Ustica and Lipari and at Vallo della Lucania. In 1930 he was again banished for five years together with other leaders of Giustizia e Libertà. The Rosselli brothers were murdered in France , by French Fascists acting on behalf of the Italians. Parri remained in contact with Giustizia e Libertà, and in 1942 founded the Action Party, an anti-fascist liberal socialist movement . After the armistice Parri was appointed coordinator of the recently constituted Comitato Militare of the CLN of Milan. Parri was well aware of the importance the Allies gave to the fate of their prisoners of war who following the armistice were in a precarious position and determined to do something to help.

At the time of the Italian Armistice on 8th September 1943, there were some 80,000 Allied Prisoners of War in Italy. The vast majority were British and Commonwealth troops who had been captured in the Western Desert between 1940 and 1942, but there were also Greeks, Slavs, Free French and others. During the 45 days of Marshal Badoglio’s Government between the fall of Mussolini and the Armistice, the British had already warned the Italians not to hand any Allied prisoners in their custody over to the Germans, During the Armistice negotiations Churchill had insisted that the Italians did everything possible to prevent this happening. Article 3 of the Armistice provided that;

“All prisoners or internees of the United Nations to be immediately turned over to the Allied Commander in Chief, and none of these may now or at any time be evacuated to Germany.”

The Italians attempted to honour the terms. However, the position was not helped by the notorious British “Stay Put order”- which instructed British POWS to stay in their camps and not to attempt mass breakouts. This was reinforced by the Senior British Officers in some camps threatening their men with Court Martial if they ignored the order. So in some camps the Allied Prisoners were still there when the Germans arrived. In other camps there were mass break outs. At Camp PG 49 at Fontanellato near Parma, 600 officers left the camp and disappeared into the surrounding countryside.( see Eric Newby’s “Love and War in the Apennines”) In the north of Italy there were POW Camps and work camps around Vercelli and Novara, and in the Lomellina around Pavia and Vigevano, south of Milan. There were also camps at Turin, Bergamo , Verona , Padua and in Emilia Romagna near Piacenza and Parma. For men escaping these camps , it was safer to head north towards Switzerland rather than trying to head south and cross to the Allied Lines. Many of the men had no knowledge of Italy , its geography, transport routes or language and they were in need of local help to get away.

The Vercelli rice fields - after 8 September many POWs simply walked out of the work camps

Following the armistice the Italian Government had fled south to Brindisi and the Germans occupied the north of the country. There was no Italian authority present to protect the escaped POWS wandering defencelessly around the countryside of Northern Italy. Many noble and brave Italians were helping them out but some coordination was needed. Parri saw it as the duty of the Comando Militare to take the place of the Rome government and to uphold the agreement made in the armistice to give these prisoners of war help. Parri accepted Baccigaluppi’s proposal to set up a special 'Service' of the CLN to help the prisoners of war. Bacciagaluppi was ideal to organise the network, with his good knowledge of English, acquired from Audrey and through working for FACE and a house near the Swiss border. Together with Agostino Giambelli of the Christian Democrat Party and Giovanni Battista Stucchi of the Socialist Party, Bacciagaluppi had already helped some British prisoners escape. At that time of the Armistice he was working outside of Milan at Busto Garolfo with the telephonic equipment section of FACE which had something like 200 employees. Many of these employees had already proven their credentials in the anti-Fascist strike of March 1943 and in sabotaging German military equipment and installation of the telephone lines for the partisans of Pizzo d ‘Erna near Lecco. Around ten employees formed the nucleus of the escape network. They had the advantage of working for a company having close links with the military and the excuse of moving around for the installation of telephone exchanges. These men were later joined by others of antifascist sympathies. The objectives of the newly formed escape network were:

a) to help prisoners of war reach Switzerland, the Allied lines or partisan bands, depending on their choice, establishing priority on the basis of the area, their health and other circumstances;

b) to provide those prisoners who did not want or were unable to move from their hiding-place with food, clothing, equipment and medical assistance;

c) to make contact with individuals or groups who were prepared to help with donations or with direct assistance and to guard against any activity which might expose the prisoners to risk or to be detrimental to the national cause; and

d) to have contact with the Allied authorities in order to receive official instructions and help.

The escaped prisoners in Vercelli could almost see Switzerland getting there was rather more difficult

As soon as the network was set up and a plan of operations agreed, the first group went into action, making the necessary contacts, preparing operational bases and trying at the same time to deal with the first urgent requests. On 25 October, the delegate of the Comando Militare at Lugano, Alberto Damiani, was able to communicate to John McCaffery, the representative of the British Special Operations Executive in Bern that 5,000 of the 12,700 prisoners of war assumed to be at large in northern Italy, had been helped in various ways outlined above. Contact with the prisoners was easy at the beginning, as they were concentrated near to their former camps in areas which were accessible and fairly safe. However, after the first rastrellamenti by the Germans and the Fascists many were captured and some were killed, consequently they moved to safer places and became more suspicious. It then became necessary to use a former POW or someone who spoke their language or that they already knew as an intermediary. It was often difficult to persuade the former prisoners to leave their hideouts, because they believed the liberation to be imminent, and later due to the ties they formed with the Italians who gave them shelter and helped them. Despite these difficulties by mid December 1943, an average of 10 prisoners a day were being taken across the frontier to Switzerland by the Service, with only a small percentage of losses amongst the agents of the Service. Later, problems began to increase and so did the losses. The Germans tightened security along the border and the authorities’ offered bounties for information. Many brave Italians were betrayed to the authorities for cash for helping prisoners and some were killed on the spot by the Germans or the Fascists or sentry to camps.

In the early days Baccigaluppi’s close collaborator and second in command was Arturo Paschi. The 29-year-old Paschi , had been born Arturo Pasches to Jewish parents in Trieste. He had enrolled in the army as a volunteer , aged only 16 and rose to be a sottenente in the Alpini. Arturo’s aspirations of a military career and subsequently his ambitions to become a lawyer, ended as a result of Italy’s Racial Laws , enacted in October 1938. He was effectively barred from both the Military and the law. The same laws also led to restrictions on his sporting activities, Arturo had been a keen sportsman in fencing and alpine pursuits He was excluded from the Fencing Circle as result of the Racial Laws and then also from the Alpine Club, although he was allowed to continue as an external member, Arturo became a member of Justice and Liberty part, taking part on their first conference on 6 /7 September 1943. Ferruccio Parri then introduced him to Baccigaluppi’s Escape Organisation. Paschi assumed the nom di guerre “Paoli” and travelled around with forged papers in the name of Alberto Pasini. On 10 December 1943, he was ambushed in Milan by a group from the UPI/GNR who had been waiting hidden in a taxi. As Arturo tried to escape , he was machine gunned by the Fascist agents. He was taken to Milan’s Niguarda hospital in critical condition with multiple gunshot wounds to the abdomen and not expected to live. Nevertheless , Bacciagaluppi was able to arrange for him the escape to from the hospital, he was wheeled out and placed in a van, arranged by Giambelli who was a manager at the Gondrana Transport Company. Radio London announced Paschi’s arrival in Switzerland transmitting three times the message 'Nino's secretary has arrived safely'

Milan's Niguarda Hospital from where the critically injured Arturo Paschi was rescued and smuggled across the border to Switzerland.

Bacciagaluppi’s network ran several different escape in Northern Italy. The area around Luino had the advantage of being on the railway line Genoa – Novara – Luino, which in peacetime had run through into Switzerland and had been projected as a route between the port of Genoa and the Gotthard pass, which avoided the need to pass through Milan. Trains from the stations in the Vercelli rice fields , at Santhia, an Germano and Vercelli went through to Novara, where a change could be made to the Luino line.

The railway line from Novara to Luino ( just outside Calde)

From the rice fields around Vigevano and Abbiategrasso trains went to Milano Centrale. From Milano Centrale a separate line ran through Legnano, Gallarate and Laveno before it joined the lakeside route to Luino . It was not quite that all railways went to Luino , but most of them did. If you go to Luino today, its railway station seems rather too large for the size of the town and the few passenger trains arriving there. But before the war and the Schengen agreement it was an International Station with a large Customs and passport hall for travellers going on to Switzerland. In wartime , Luino station was heavily controlled and through trains no longer ran to Switzerland. The risk of being picked up there were obviously quite high. . So generally it was safer for fugitives heading for Luino, to disembark at the previous smaller stations in the small resorts town of Caldè and Porto Valtravaglia on Lake Maggiore.

Caldè railway station

Porto Valtravaglia Railway Station

The International station at Luino

In Caldè they were sheltered at Baccigaluppi’s house, which was the centre of local operations and from there taken by boat beyond Luino , where local guides took them on a five-hour march towards the frontier. The Germans patrolled the lake, so attempting to reach Switzerland purely by boat as in Hemingway’s “ A Farewell to Arms” would have been a risky enterprise. For fugitives arriving by train from Varese and Novara, there was a safe house at Cittiglio .

The road up to Voldomino from Luino

After being hidden in either place many fugitives were dispersed to Voldomino , a small village above Luino which was closer to the Swiss frontier either by bicycle or on foot . Voldomino is around ten to fifteen minutes walk from the centre of Luino and the railway station. To walk there , you cross the road bridge over the River Tresa. At this point the river, which runs from Lake Lugano to Lake Maggiore is firmly within Italian territory, but a few kilometres upstream, it starts to form the border between Italy and Switzerland. Although fenced and guarded, the river provided another potential crossing point for fugitives to try and cross into Switzerland.

The River Tresa in Luino- further upstream it becomes the frontier between Italy and Switzerland

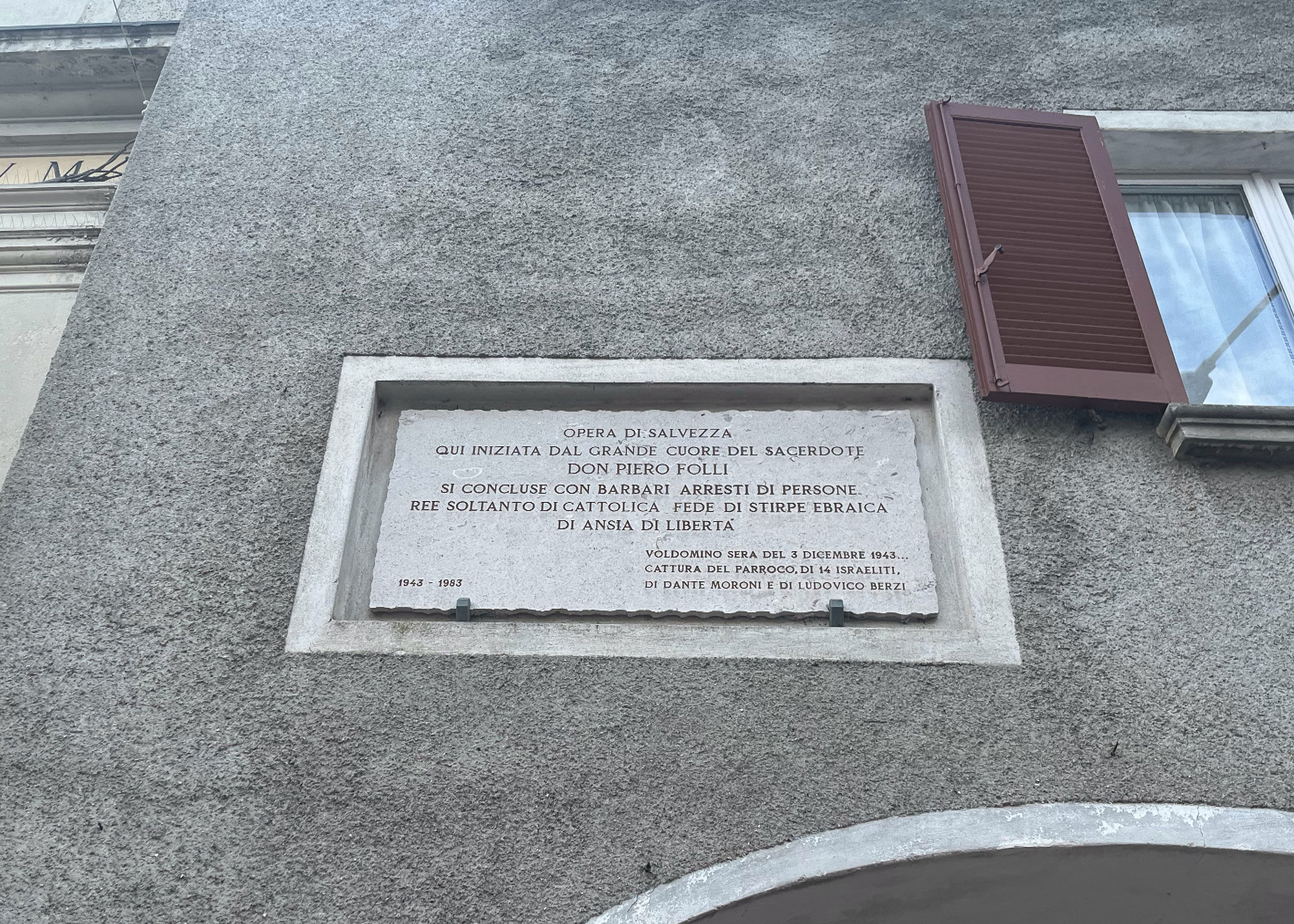

Vital to the Voldomino operation was local priest don Pietro Folli, who was already part of the OSCAR (Organizzazione Soccorso Cattolico agli Antifascisti Ricercati) network who kept his house, the church and the oratorio open for any fugitives in need. Don Pietro was born in Premeno (VB) on 18 September 1881. While still in the seminary he sided with the workers in the struggles of 1898. He became a priest on 28 May 1904. His social conscience and commitment to others led him to found evening schools, hold agricultural conferences, work as an assistant to the Labour League, and personally participate in the spinning mill strikes. He also become a correspondent for the newspapers Il Lavoro and Tribuna Sociale. In 1909 he was transferred to Tradate where he founded a "worker's league" - to provide Catholic workers with adequate tools against the spread of socialist doctrine - and created the "Giovane Tradate" to bring together the young people. In 1915, at the height of the World War, he was parish priest in Carnisio, still close to the people: he created a factory for the repair of military uniforms, which represented concrete help for the country. With the advent of fascism Don Piero was registered as an opponent of the regime suffered the humiliation of castor oil and beatings. He was accused by many of being too modern and for this reason he is transferred again, this time to Voldomino. There, he took particular care of the young people, setting up a gymnastics team , an amateur drama club, a library and a work school.

The church and piazza in Voldomino

Immediately after the armistice Don Folli came into contact with the CLN, apparently he aided Croce’s San Martino partisans by signalling the passage of Nazi convoys with spread out sheets. His help also extended to allied prisoners, the politically persecuted (Piero Malvestiti, the Communist leader Mauro Scoccimarro, Dino Segre) and the Jews. The oratory of Santa Liberata was always open to fugitives. Although the expatriation of Jews was not included in the military objectives of the CLN, Don Piero maintained that it was "a Christian obligation to save those families". His network was known to the allies and as far afield as the French Riviera, Tuscany, Liguria, particularly by Massimo Teglio and Cardinal Boetto of Genoa. There are some surprises among those who passed through the Voldomino safe house, the writer Dino Segre, otherwise known as “il Pittigrilli” was perhaps the most curious. Although Jewish and banned from publishing in Italy, Segre had been a collaborator with the fascist Secret Police, the OVRA in Paris until his exposure by the French police, rendered him useless to them. Despite renewed offers to collaborate, Segre’s Jewishness saw him continued to be persecuted in Italy, so he left for Switzerland. After the Fascist assault on the partisan positions at nearby Monte San Martino in November 1943, don Folli sheltered don Mario Limonta the chaplain of Carlo Croce’s partisan group “Cinque Giornate”, while he recovered from his wounds , don Mario was able to cross into Switzerland on 2 December 1943 and rejoin the remains of his partisan group.

Jewish fugitives were sent up to the Luino area, by Cardinal Beotto in Genoa. Normally the parties were accompanied by another priest don Gian Maria Rotondi. Rotondi had probably expatriated two or three groups pf Jews into Switzerland, this time a group of fourteen were sent back from the Swiss border and had to return to shelter in Voldomino. However, time was running out for don Piero’s escape centre in Voldomino.

Memorial to don Piero Folli in Voldomino

On December 3, 1943, a punitive Nazi-Fascist expedition arrived in. Don Piero was tied to the railings of his oratory, severely beaten, insulted, offended and spat upon. Inside the rectory the Jewish fugitives were hiding with Don Repetto, secretary of the archbishop of Genoa. Also present was Mr. Pio Alessandrini and the engineer. Mario Bongrani. Shots were fired and the fascist squads devastated the house. Taking advantage of the confusion, Alessandrini and Bongrani managed to escape, Fortunately the fascists did not do a thorough search and missed the records of previous expatriations. The Jews were grouped outside, hands on the backs of their heads, are forced to march in the rain. Many of don Piero's collaborators were arrested in the town, almost all of them great experts on the border areas. Among his collaborators were the blacksmith from Germiniaga, Secondo Sassi, who had often facilitated particularly difficult border crossings. On one occasion he had constructed a raft to get escaping children across the river into Switzerland. An eyewitness account of the raid reported ;

“On December 3, 1943, I was emptying the letterbox in the square in Voldomino when a truck arrived with about twenty fascist militiamen and some Germans. They got out as if in an assault and rushed towards the rectory, shooting at the windows. Then they entered and dragged Don Folli out, chaining her to a nearby railing. They insulted him by calling him a "traitor" and "red priest" and beat him bloody, while from inside the house came the sound of broken household goods then thrown out of the window. They immediately found the Jews and the parish priest's other guests; they were lined up outside and placed with arms raised against a wall. There was among them an elderly woman who had her hands in a fur muff and who remained awkward for a few moments. Some of her money fell to the ground but in the meantime they attacked her by hitting her violently with the butt of his rifle. They loaded her onto the truck where she was already dead: the head of the expedition collected her money.”

Albergo Venezia which was the base for the SS in Luino

The responsibility for the raid was the work of fascists who came from Milan from the Legione "Ettore Muti", accompanied by the German SS from the Elvezia hotel in Luino. Alteady in November 1943, four members of the "Ettore Muti" had apparently arrived in Luino in plain clothes. Posing as partisans, they made contact with some anti-fascists from Luino, promising them weapons and ammunition. The four took note of the anti-fascists, prepared the trap and on 3 December reinforcements from the "Muti" in Milan and SS Germans present in Luino were sent to Voldomino. After a short stay at the Elvezia hotel in Luino, headquarters of the German SS where they were interrogated, all the arrested were sent to San Vittore. The Jews were also transported to San Vittore, where the Austrian Harry Klein, from DESALEM in Genoa, passed himself off as an Apulian, managed to save himself.. Don Piero Folli and Don Gian Maria Rotondi were released after a few months, thanks to the intervention of the Milanese Curia. After months of torture and other interrogations had failed to turn up any evidenced Secondo Sassi, and the other local collaborators were released on Easter Monday 1944. The precise fate of the Jewish refugees is not recorded but can be imagined. During the Shoah , 261 Jews were deported from Genoa- only 20 returned alive. Around 230 allied prisoners may have escaped through the Voldomino route, the majority between September and December 1943, when following the arrest of don Pietro the route was seldom used.

Milano Central Station became a pivotal hub of the escape network

Milan Central Station, a pivotal hub for the escape network

When the route from Luino became too difficult other routes were used. Prisoners were bought into Milan from all over Northern Italy. In February 1944 a group of British prisoners passed through on the way from the Padova area. The six prisoners escorted by three guides arrived at Padova Station in the morning to take the train to Milan. One of the guides had just come down from Milan, so was up to date on the position there. The prisoners were given overcoats and scarves to keep out the February cold, food for the journey , false ID papers and an Italian newspaper to read or pretend to read, One guide took the fugitives to the centre of the train the other two boarded the front and rear of the train, so they could give prior waning of any controls on board . Prior to the war, the journey would have taken about four or five guards. By 1944, the Italian railways had become severely damaged and disrupted by Allied air raids, tracks were destroyed and sever delays incurred. During the journey, the train might have been delayed by air raids or alarms for air raids. -it must have been a tense slow journey. In the end the train arrived at Milan Centrale after curfew time( the normally from 21 to 5 ) so, it is clear how long the journey must have taken. Once at Milano Centrale, the group could not leave the station.

Curfew time at Milan Central Station

The waiting rooms were frequently patrolled and not regarded as safe, so they were forced to doss down in trains parked at the station ready to depart the next morning. After what must have been a cold and tense night, the fugitives were finally allowed out after 5am and taken to a nearby safe house to rest and prepare for the next part of their journey. Having rested for most of the day they went back to take a train up the eastern side of Lake Como, on the Milano -Sondrio line. Again precautions were taken on the train, the passengers were given tickets for various destinations up the lake to not attract too much attention . Leaving Milan around 1630 , they reached Dervio , around two and half hours later, where they all descended and waited for the torchlight signs of local guides.

Dervio Station on the Railway line from Milan to Colico and Sondrio used by the Milan Escape Network

From Dervio, there followed a boat trip across the dark cold waters to Cremia, about 2.3 km at one of the Lake’s narrowest points, At Cremia., they rested and were equipped with mountain clothes before they spent to nights, climbing through the snow-covered peaks up through the Val Cavaragna and into Switzerland

A boat typical of Lake Como

Across the Lake and over the mountains was Switzerland

In 1943 the trains were delayed by enemy action/ these days the reasons are less clear

!940s trains were probably more reliable

Of course, Bacciagaluppi did not run the Milan Centre alone, he had a network of supporters on whom he relied, people who coordinated the local activities , local guides, the farmers who sheltered prisoners for a few days and individuals who provided safe houses in Milan. Every part of the network put themselves at risk of the terrible consequences of being caught. Members of the network included:

Enzo Locatelli – a telephone engineer who organised crossings around Lake Como and the Valtellina, and then took charge of the area around Bergamo and Brescia – arrested on 3 April 1944

Carlo Mussa Ivaldi Vercelli from Turin , an engineer and long-time antifascist who had been a member of the Giustizia e Libertà formation in Val Pellice near Turin. He was arrested and sent to San Vittore prison in March 1944, but managed to escape

Franco Plazzotta, a naval officer in charge of zone 4 -Veneto .Arrested 25 May 1944.

Bruno Tamborini , originally from Boston, USA who was in charge of zone II , Lombardy , and the area around Varese. He was arrested in July 1944.

Sergio Tornaghi, from Milan – part of the transit organisation. Arrested and deported to Austria, where he died in the Camp of Melk.

Among other local agents helping in the area were the factory owners Ulisse Cantoni and Bruno Giovannoni, and Pierina Zappeli.

One of Bacciagaluppi’s strictest collaborators was Sergio Kasman. Sergio was born in Genoa on 2 September 1920, his father Giovanni came from the Ukraine , was Jewish and emigrated to Italy, where he worked as a tailor. , known as “Forbice d’Oro”. (Golden Scissors) Giovanni was also an aspiring Opera singer , who had performed at Scala di Milano, San Carlo di Napoli, and the Operà in Paris. In 1932 his family moved to Chiavari, , Giovanni stayed in Genova to work , but always dreamed of moving the family to America and performing at the Met. The introduction of the Racial Laws in 1938 further motivated this choice. , and on 23 February 1939 he embarked on the liner Rex for New York. Hoping his family would join him, he wrote and sent money to the family in Chiavari but in the end the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour , the Italians declared war on the United States, and nobody could join him.

Meanwhile, Sergio was called up to the Army training school at Pinerolo, promoted to sergeant in the artillery and on 8 September 1943., his unit was part of those who mounted a defence of Rome from the attacking Germans at Porta San Paolo. Hopelessly outgunned by the Germans they subsequently disengaged , the unit disbanded, and the men went home. After five days, Sergio returned to Chiavari. He joined the resistance , initially alongside OSCAR directed by the priests’ don Andrea Guetti e don Aurelio Giussani. Sergio helped anti-fascists across into Switzerland , under the nom di guerre Marco Macchi. His seriousness and dedication grew his reputation. During one mission in Switzerland, he found that his brother Marcello, had made it across the border and been interned. In March 1944, while Sergio was in Switzerland, he met with Ferruccio Parri and Leo Valiani, They were there to persuade the Allies to give greater support to Giustizia e Libertà. Sergio went back into Italy on their behalf taking the Luino route and returned to Milan where Parri had appointed him Chief of Milan for the action squads of Giustizia e Libertà. He was staying near piazza Baracca, with another clandestine Bepi Baltoli when he heard about the arrest and detention of Bacciagaluppi.

On 4 April 1944, Bacciagaluppi was arrested at the office of a colleague of FACE during a visit to Milan. He was detained by the Fascist police together with a colleague, a trusted but external supporter of the Service, and Enzo Locatelli, who was in charge of communications and false documents. Since he was sure that another of his collaborators , the Dutchman Pietro De Lange, was by then safely in Switzerland Bacciagaluppi told the Germans he was willing to collaborate and gave them De Lange’s name and address, although the Germans obviously did not find him , they began to trust Bacciagaluppi, which gave him a certain freedom of movement and the opportunity to work in the prison work shop where he managed to copy the keys that were to be used in the escape attempt. Bacciagaluppi was imprisoned in San Vittore along with a Canadian paratrooper Lieutenant George Robert Paterson. Paterson, who was an engineer in civilian had been part of Operation Colossus a daring British mission in February 1941 to destroy an aqueduct on the river Tragino in Campania . Paterson was captured and subsequently imprisoned at Sulmona ( PG 78) , Pisa, Padula ( PG 35) and Gavi (PG 5). In May 1941, Paterson was one of eight officers who escaped from an organised walk; he was, however, recaptured the same day. Almost a year later, at Pisa, he participated in an attempt to break through into an adjacent church; this project was discovered before the officers emerged. After these escape attempts, Paterson was sent the Fortress of Gavi which was the Italian equivalent of Colditz. When the Germans took over Gavi Camp after the Italian Armistice, they began to transfer all the Allied prisoners of war to Germany. Paterson managed to escape from the train, he was then helped by friendly Italians and sent to a partisan band near Brescia. There he joined the escape network and began helping escaped prisoners come down from the mountains and join the Milan escape route. Captured by Fascists early in January 1944, he was handed over to German custody, then being sent San Vittore in Milan.

San Vittore prison in Milan

Baccigaluppi’s arrest threw the Service into crisis. Many of the contacts had been lost and there was a general disorder amongst the helpers when Sergio Kasman took over. He was, however, able to link up the various sectors again and make it active again However life was getting more dangerous in Milan , the city was not only occupied by the Germans with their security apparatus of the SD/SS , the organs of the RSI the UPI and GNR , various Fascist Death Squads and an army of paid touts. It became Kasman’s idee fixe to get Bacciagaluppi out of prison. On 9 July 1944, Kasman who was tall with blonde hair dressed in SS Uniform and passed himself off as a German, in order to get Bacciagaluppi, Arialdo Banfi and the Canadian paratrooper George Patterson out of the prison. Banfi was another clandestine leader of Giustizia e Libertà. Bacciagaluppi was by now too well known in Milan and he and was forced to expatriate to Switzerland, using his own escape route. His wife Audrey and son Marco had gone on to Switzerland ahead of him. Kasman now became one of Milan’s most wanted , with everyday becoming more difficult for him to hide , he maintained contact with the Resistance and heard that his youngest brother Roberto had been arrested back in Chiavari. Kasman put together a plan similar to the San Vittore breakout, once again he donned his German disguise and in a smoothly executed operation liberated Roberto from custody., Kasman hugged his brother and went back to Milan, in a third-class carriage. Back in Milan , the net was tightening Kasman and the activists of Giustizia e Libertà were forced to move every few days, Then Ettore Piantoni, commander of the GAP for the Porta Venezia district was picked up, under torture at the barracks of the Muti he gave up his former comrades. On 9 December 1944 Piantoni, lured Kasman to a fake meeting at piazza Lavater a few blocks from Corso Buenos Aires. At the corner of via Ramazzini and the piazza Lavater, Alceste Porcelli and Arnaldo Cagnoni of the UPI of the Muti were waiting for Kasman to show. Kasman’s joy at meeting Piantoni, turned sour as he felt the pistols of Porcelli and Cagnoni in his back. , Porcelli ordered him to raise as his hands. As they forced him towards a car , Kasman made a run for it. Porcelli opened fire, shooting him several times in the back . Kasman was taken to the nearby post of the Guardia Medica , where he died . Sergio Kasman, who had sprung Bacciagaluppi and his brother and who had done so much to assist allied POWs escape could not escape himself, gunned down by his own countrymen.

The street corner in Milan where Sergio Kasman was gunned down

Memorial plaque for Sergio Kasman

Kasman was succeeded by his deputy Dario Tarantino, a former air force officer from the Piedmontese resistance. Unfortunately, Tarantino did not last long in his role, on 24 January when he was arrested in Milan on his way back from Lago Maggiore . He was hiding at a safe house in via Goldoni when the Brigata Muti arrived. He was taken to their barracks in via Rovello and tortured , then they drove him out to the Milanese hinterland at Bruzzano, where they shot him and dumped his body. The citizens of the area gave him a decent burial.

The area where fascist killers dumped Dario Tarantino's body

Dario Tarantino remembered

Following the arrests and killings the number of frontier crossings fell rapidly and the last expedition took place in March 1945. In Lugano, Bacciagaluppi became Military Delegate of the CVL. until the beginning of March 1945 when he was arrested by the Swiss police for the infringement of neutrality, he was interned at Bellinzona and then at the Majestic Hotel in Lugano before he escaped through France to Rome with the help of the Allied authorities. Bacciagaluppi’s presence in Switzerland enabled him to make direct contacts John McCaffery in Berne and his assistants Lancelot. C. De Garston, the British Vice-Consul in Lugano and representative of MI9 and Major John Birkbeck (a former POW who had escaped to Switzerland , who had taken on the role of liaising with the Italians in Lugano) and also with Allen Dulles of the OSS in Berne and his assistant D. Price Jones in Lugano.

There were other networks providing assistance to fugitives in Northern Italy, but they all tended to move towards Bacciagaluppi. Most notable was the network run by John Peck in the Vercelli area. The Australian Peck, was an inveterate escaper. Having missed the evacuation of Crete , he had headed up into the mountains, there he was captured by the Italians and taken to Rhodes , he tried escaping from there by boat across the narrow sea to Turkey but was recaptured. The Italians then sent him to Italy, first to Camp PG75 at Bari, them to the larger camp PG 57 Gruppignano, which had been constructed to hold Australian and New Zealand Other Ranks. By April 1943, the Italians were suffering from a shortage of agricultural labour, so they sent around 800 Australian OR prisoners across to the other side of the country to the rice fields around Vercelli and Vigevano. Camp PG106 Vercelli was not one single camp, but consisted of 29 separate work detachments allocated to different farms. It was back breaking work in the hot Italian summer, but some of the prisoners preferred it to the enforced idleness of the large camp . The work vamps were lightly guarded and working in the rice fields on the plain the prisoners cold see the Italian Alps with the knowledge that Switzerland was on the other side. Peck started at the camp at San Germano, he escaped and was recaptured . He tried again and this time ended up in the rather more secure Vercelli prison, he was still there at the time of the Armistice. In most of the work camps the guards simply abandoned their posts and went home. Peck had to wait for the citizens of Vercelli to liberate the prison.

San Germano near Vercelli where Johnny Peck was imprisoned

Once out of prison, Peck set about looking for other prisoners to take to Switzerland. With the help of a network of local people , he went oy to contact the prisoners hiding out in the scattered farms. By the end of September, he had gathered together around 20 and took them across the passo di Monte from where they could get down to the Swiss border. Peck did not join them, he chose instead to go back to the rice fields and assemble another group to take across. His ad hoc local network became a committee and to cope with rowing numbers, they started putting the prisoners on to trains, where they could get to the easier crossing points on Lake Maggiore. At its peak, Peck’s network was running around 60 to 70 prisoners a week to the Swiss border, by this time Peck was in contact with the CLN and in December 1943, he met with Bacciagaluppi and merged his network into Baccigaluppi’s organisation. Peck estimated that as an independent operation, he had got around 200 prisoners to the border. By December 1943, the numbers of prisoners at large had started to dwindle. Many had been recaptured, others had joined the partisans and others simply decided to stay put. Peck decided to join the partisans instead.

In his final report on the escape network, Bacciagaluppi reckoned the Service had spent 7,800,000 lire, of which 4,750,000 came from CLNAI funds, 2,000,000 from the Allies and 1,050,000 from private sources ( for example the sums paid personally by Lina Crippa Leoni). Out of a total of around 350 agents, sub-agents and occasional helpers, 20 were killed (6 executed, 5 killed in action, 9 dead after deportation), 3 wounded with permanent disability, 17 deported and 48 imprisoned in Italy. During the period of co-belligerence, the Allies did not really know what to do with the Italian co-Belligerent forces from the Regno nel Sud. In the end they grudgingly allowed a role for the Italians, The activity of the CLNAI in support of the Allied prisoners of war, was perhaps the only help carried out with the full consensus of the Allies themselves. It contributed without doubt to the lessening of the diffidence and the suspicions towards the Italians on the part of the Allies. At the end of hostilities, the activities of people like Bacciagaluppi, Kasman , Paschi . Tarantino. Lina Crippa Leoni and don Petro Folli contributed to the rehabilitation of the good name of Italy and the Italian people with the Allies.

Piantoni, was tried after the war for betraying Kasman and several others, but he was acquitted. Porcelli faced a raft of charges for his activities with the Brigata Muti . Kasman had been “shot while escaping “ but Tarantino had clearly been murdered, Porcelli was convicted but served hardly any gaol time as a result of the post-war amnesty. Sergio Kasman was reinterred at the heroes’ plot in the Musocco Cemetery in Milan on 22 October 1945. Roberto and his mother were present, along with Ferruccio Parri by now the Prime Minister of Italy. On 24 April 1946, Sergio Kasman was awarded the Italian Gold Medal for Military Valour.

Bacciagaluppi joined the Allied Screening Commission in Rome , he returned to Milan on 27 April with a an Allied Special Force convoy which had left from their base at Siena, under the orders of Colonel Hedley Vincent. In Milan he acted as coordinating officer between the general command of the CVL and the Patriots Office of the Allied Military Government ( AMG) , commanded by Lieutenant Colonel A.R.A. de Garston (brother of L. C. De Garston of the SOE at Lugano). Until September 1946, he also worked at the Service Office investigating and documenting the help given by Italians to Allied prisoners and reporting on this to the Allied Screening Commission. Then he abandoned politics and in 1948 took over the direction of the Autodromo di Monza and other notable roles in Italian motor spots.