Back on the Peace Trail in Stresa

After looking at the post First World War peace conferences at Rapallo and Locarno, here we look at what was perhaps Europe's last and best hope for peace at Stresa in 1935. Unfortunately an ailing British Prime Minister and a failure in Anglo-French relations blew the opportunity and the hope of keeping the Italians out of a German Alliance.

The background to the Stresa conference was Germany's declaration of its intention to build up an air force, increase the size of the army to 36 divisions (500,000 men) and introduce conscription, in March 1935. All these actions were direct violations of the Treaty of Versailles, which limited the size of the German Army to 100,000 men and forbade conscription. Great Britain and France got together with their wartime ally Italy to address the situation. Italy was of crucial strategic importance; its geographic location made it vital for a defence of Austria. In July 1934, following the Nazi putsch, Italy had sent four divisions to the Austrian border. With Italy against them, the Germans would be required to split their forces to guard their southern border, weakening their forces along the French and Belgian borders. Reaching an agreement with the Italians at Stresa was vital to the future of Europe.

On 25 July 1934, in the midst of difficult social and political tensions, and with the knowledge of official German positions, 154 SS men disguised as Austrian Bundesheer soldiers and policemen pushed into the Austrian chancellery. Dollfuss was killed by two bullets fired by Nazi Otto Planetta, an Austrian Nazi who had been discharged from the Bundesheer for hid Nazi sympathies. The rest of the government was able to escape. Another group of the putschists occupied the RAVAG radio building and broadcast a false report about the putative transfer of power from Dollfuss to Anton Rintelen, which was to have been the call for Nazis all over Austria to begin the uprising against the state. There were several days of fighting in parts of Carinthia, Styria and Upper Austria as well as smaller uprisings in Salzburg. In the the Kollerschlag area on the Bavarian-Austrian border, a division of the Austrian Legion invaded Austrian territory and attacked the customs guard and a police station. A German courier was arrested at the border crossing in Kollerschlag who was carrying precise instructions for the putsch. The death of Dollfuss enraged Mussolini, whose wife, Rachele, was entertaining the rest of Dollfuss's family at the family vila in Riccione. the news reached him at Cesena, where he was examining the plans for a psychiatric hospital. Mussolini personally gave the announcement to Dollfuss's widow, He mobilised part of the Italian army on the Austrian border and threatened Hitler with war in the event of a German invasion of Austria to thwart the putsch. Then he announced to the world: "The independence of Austria, for which he has fallen, is a principle that has been defended and will be defended by Italy even more strenuously". Just to make his point Mussolini had a statue of Walther von der Vogelweide, a Germanic troubadour in the main square in Bolzano replaced with that of Drusus, a Roman general who conquered part of Germany. He also put at the disposal of Ernst Rüdiger Starhemberg, who was on holiday in Venice, a plane that allowed him to rush back to Vienna and mobilise his militia against the putschists. In the end the Putsch failed, but Mussolini continued to be concerned about German intentions in Austria.

The background to Stresa was further complicated by events in the Horn of Africa, with tensions on the border between the Italian Colony of Somalia and the independent empire of Ethiopia. A Treaty between Italy and Ethiopia in 1928 had established the border between Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia. In 1930, Italy built a fort at the Walwal oasis in the eastern Ogaden, in a boundary zone between the nations and well inside Ethiopian territory. Although on 29 September 1934, Italy and Abyssinia had renounced any aggression against each other, that turned out to be short lived . On 22 November, a force of 1,000 Ethiopian militia with three fitaurari (Ethiopian military-political commanders) arrived near Walwal and formally asked the Dubats garrison stationed there (comprising about 60 soldiers) to withdraw from the area. The Somali NCO leading the garrison refused to withdraw and alerted Captain Cimmaruta, the commander of the garrison. The next day, in the course of surveying the border between British Somaliland and Ethiopia, an Anglo–Ethiopian boundary commission arrived at Walwal. The commission was confronted by a newly arrived Italian force. The British members of the boundary commission protested but withdrew to avoid an international incident. The Ethiopian members of the boundary commission, however, stayed at Walwal. In early December there was a skirmish between the garrison of Somalis, and a force of armed Ethiopians. Both sides claimed that the other had instigated the aggression . In the end, approximately a hundred Ethiopians and fifty Italians and Somalis were killed. Neither side did anything to avoid or deescalate the confrontation. On 6 December, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia protested the Italian aggression at Walwal and the Italians demanded an apology for Ethiopian aggression, followed up with a demand for financial and strategic compensation. On 3 January 1935, Ethiopia appealed to the League of Nations for arbitration of the dispute. A subsequent analysis by an arbitration committee of the League of Nations absolved both parties of any culpability from all events. Shortly after Ethiopia's initial appeal, French Minister of Foreign Affairs Pierre Laval met with Mussolini, in Rome. The meeting resulted in the Franco-Italian Agreement, which gave Italy parts of French Somaliland redefined the official status of Italians in French-held Tunisia and essentially gave Italy a free hand in dealing with Ethiopia. In exchange, France hoped for Italian support against Germany. Matters remained tense and on 25 January, five Italian askaris were killed by Ethiopian forces near Walwal. On 10 February 1935, Mussolini mobilised two divisions and began to send large numbers of troops to Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. On 8 March, Ethiopia again requested arbitration ,noting the Italian military build-up. and again appealing to the League for help. On 22 March, the Italians agreed under pressure from the League to submit to arbitration but continued to mobilise troops in the region.

The British delegation to Stresa was led by Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald’s , by that time a shadow of his former self. MacDonald and Foreign Secretary, Lord Simon. Since they had to wrap up a morning Cabinet meeting they took a plane from Hendon to Le Bourget in Paris, where they connected with the train for Stresa. The rest of the British delegation had already left London in the morning by train. In those days the Simplon Orient Express from Paris through the Simplon Pass to Domodossola and followed the shores of Lake Maggiore before reaching Milan and onwards to Bucharest. As far as Domodossola the line had been constructed by the Swiss, there the train was attached to an Italian locomotive since the voltage changed on the Italian railways. After Domodossola the train headed along the shore of Lake Maggiore with stops at Pallanza and Stresa giving passengers a view Isola Bella and across the lake before heading for Milan.

Before the railway arrived Stresa had been difficult to reach, requiring a stagecoach across the Simplon Pass, or alongside the lakeside from Arona once the Italian railways had reached there. Nevertheless tourism began to develop, in 1859,the Hotel Milan opened in the centre of town. In the 1860s, Stresa began to expand along the lake shore, The Omarini brothers set up the Società Unione dei Grandi Alberghi, chaired by Arturo Omarini and in the spring of 1860 they purchased some land in front of Isola Bella. Construction of the Grand Hotel des Iles Borromées began in the winter of 1861, and it was opened in March 1863. Following the opening of the Simplon tunnel in 1906 and the arrival of the railway, Stresa began to develop further. The Grand Hotel des Iles Borromées expanded and local entrepreneurs bought the structure of Villa Martini on the lakefront , and constructed the Regina Palace Hotel, inaugurated on 8 March 1908. Stresa was an ideal place for a conference, easily reached from France and Great Britain , with a plenty of quality hotel accommodation for delegates and the press and a secure venue on the Isola Bella.

The Hotel Regina Palace in Stresa

Since the conference had been announced the podesta of Stresa, Carlo Emanuele Basile had been keen for his hometown to show its best side to the world. Basile was the scion of a noble Sicilian family but had been born in Milan and had grown up in Villa Carlotta, Stresa. Educated at the liceo of Novara and then the university of Turin in jurisprudence , he had then studied literature and embarked on a not unsuccessful career as a novelist. His most famous novel L’erede ( the -heir) was published in 1923He had first been elected Mayor of Stresa in 1914 and had served until 1927, with a break during war when he had served as a lieutenant with the cavalry regiment the Lancieri di Novara. Previously of a liberal persuasion, in 1922, Basile had hitched his wagon to the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF) and risen rapidly. Amongst his many other roles he had been appointed podesta of Stresa in 1931. As soon as the conference was announced, Basile began sending regular updates to the citizenry on how they should behave and how the town should be decorated during the conference. This was Stresa’s turn to put its best face forward to the world and Basile wasted no opportunity to stress the fact. He issued one communique after another on preparations for the conference: On the 25 March , he instructed.

“the announcement yesterday in the newspapers that on 11 April, Stresa will host a conference with the participation of the Duce and the Foreign ministers of France and Great Britain is an event of the greatest importance and one side fills our souls with joy, on the other hand , it requires the mobilisation and commitment of all our citizenry in showing hospitality”.

On 4 April, Basile issued further instructions to the residents of Stresa:

" From the 8th through to the last day of the conference , the locality must assume an aspect of festivity characteristic of a jubilees and our pride in being chose spectators at one of the most important historical events of the post war . To give the town , especially the lake front , an air of life , movement, and vitality , avoid doors and windows being shuttered this giving an air of abandonment or worse indifference to the events happening nearby. My advice, will surely be unnecessary since , I know that most absent property owners have already decided to spend the period of the conference in town, but for those who for various reasons cannot be present are requested to give precise instructions to their gardeners or a trusted person so that during the day windows remain opened and that the balconies of villas fly the Italian, French and British Flags.”

«Taking into account the regulations imposed by the competent authorities and with the intent of clearing up any doubts that have been put to me , I retain opportune to remind again that the streets of the town have to present a festive aspect during this memorable and historic days. A special responsibility relates to those fronting on the viale Duchessa di Genova and the corso Umberto I along the eminent statesmen will pass. Windows must stay opened, balconies decorated with flowers and flags and a night the front of the house should be illuminated. It is not at all true that there is a ban on looking out of windows and balconies during the passage of the dignitaries. On the other hand, it is absolutely forbidden to bring in strangers and throw flowers, posters, etc. I count on everyone's most affectionate collaboration, and I offer you all my most sincere thanks."

The Conference took place in the Palazzo Borromeo on the island of Isola Bella. The British and French delegations stayed overnight in the Grand Hôtel des Iles Borromées in Stresa. Other representations stayed at the Regina Palace Hotel. Stresa laid on firework displays, music, and flowers, flags, and garlands decorated the town. Considerable sums had been spent on sprucing up Stresa, painting buildings and servicing the Ferrovia del Mottarone. While the delegates were housed in the Grand Hotels, Fiat had provided 30 new cars to ferry them to the pier from where they were ferried to be Isola Bella by boat . The newspapers raved about how the Palazzo Borromeo had been enriched with further precious works of art including paintings by Giorgione and Tiziano .

The Prince had provided numerous servants dressed in historic seventeenth century livery. Isola Bella had been a rocky and barely inhabited island, in the sixteenth century Giulio Cesare Borromeo, uncle of San Carlo, was already the owner of the nearby Isola Madre , inhabited by only a few fishermen's houses with two small churches and a few vegetable gardens. Count Carlo III Borromeo gave the uninhabited island the name of his wife, Isabella d'Adda, from which Isola Isabella ( Isola Bella) . He bought more land on the site until he became the owner of the entire island and then in 1632 started the construction of a palace. Between 1631 and 1634, the architect Giovanni Angelo Crivelli created the general layout of the gardens, with the idea of giving the island the scenic shape of a ship. To create the terraces of land necessary for the growth of grass and plants for the park, a large amount of earth was transported by boats from the shore, to cover the rocky ground of the island. On the west side, the "Noria Tower" was erected, a hidden seat of the plumbing systems necessary for irrigation. The garden was home to orange, lemon, boxwood and cypress trees, which were mixed with crops of useful plants. Towards the middle of the century, the works suffered a setback due to the plague epidemic that affected the entire Duchy of Milan, but between 1652 and 1690 they resumed thanks to the initiative of Vitaliano VI, who with the support of his brother, Cardinal Giberto Borromeo, completed the structure, decorating it with stone decorations: balustrades, statues, obelisks, vases.

The work on the palace was also followed by other renowned architects of the time such as Francesco Maria Richini and Carlo Fontana. On the ground floor, a series of rooms open to the garden were decorated like a cave of seashells. Count Gilberto V Borromeo hosted Napoleon and his wife Josephine de Beauharnais in 1797 at the palace . It was finally completed by Prince Vitaliano X who finished the north façade and the connected pier and built the large hall on the basis of the original design. In 1935, Prince Vitaliano offered his palace as venue for this important conference.

Mussolini arrived in style the day before the conference on 10 April by flying himself from Sesto Calende in a S66 seaplane , with some panache he overflew the islands and made a theatrical landing on the lake at around midday .The Duce had flown from Forli, , following the via Emilia up the peninsula and overflying Modena. On reaching Milan he had performed a few circuits above the piazza Duomo so the waiting Milanese could get a glimpse of his aerial prowess. He had then landed at the military airfield of Lonato Pozzulo ( now part of Malpensa airport) where he had inspected a bomber squadron. Going the short distance to Sesto Calende at the southern end of Lake Maggiore, he had taken a tour of the factory of Savoia Marchetti , which manufactured sea planes from where he had borrowed the s66 flying boat. He then flew the short distance up the lake, making sure that he and his escort flight passed over the lakeside resorts before circling back over Stresa. It was all perfectly choreographed and was all captured by photographers and the film cameras. .

At Isola Bella, the Duce was met by his host Principe Borromeo and taken to a private apartment on the second floor of the Palazzo Borromeo, where he spent the afternoon. Mussolini’s entourage included his son -in-law Galeazzo Ciano, who at the time was Minister of Propaganda, and Fulvio Suvich , the under Secretary for Foreign Affairs( Mussolini was acting as his own Foreign Minister) and Air Force General Valle. Various other senior members of the regime arrived during the say, crossing to Isola Bella to pay homage to the Duce , including Achille Starace, the General Secretary of the PNF and General Teruzzi of the Milizia although they were not diplomats participating in the conference at least they would get themselves on the welcome committee for the delegations and hopefully in the official photos.

At 21.45 Mussolini was ferried back to the mainland to await the arrival of the French delegation . Stresa was illuminated and behind a phalanx of soldiers the population gave a rapturous reception to the Duce as he passed through on the way to the station ( well rapturous according to the Corriere della Sera which might have been slightly biased) When the French arrived, the 54 fanteria were there to form an honour guard at the station , and the band struck up the Marseillaise . French Prime Minister Pierre-Étienne Flandin and Foreign Minister Pierre Jean Marie Laval were greeted warmly by the Duce. They were then taken to the hotel, where they later appeared on the balcony to the acclaim of the Italian crowd. The Duce returned to Isola Bella for the night. As instructed by Basile. the buildings of Stresa all illuminated .the dark waters of the lake were swept by searchlights, set up to add to the dramatic effect.

In November 1934, Flandin ( at the age of 45) , had become the youngest Prime Minister in French history. he had previously served as Finance Minister to Laval from 1931 to 1932 Government ‘, in one of those revolving door Third Republic governments. Laval (then aged 52) had returned as Flandin’s Foreign Minister. As mentioned above, on 4 January Laval had been in Rome to meet Mussolini, beginning a diplomatic offensive intended to contain Nazi Germany by a network of alliances. Although Laval denied having explicitly given Mussolini a carte blanche in Abyssinia, for him and Flandin it was Germany that was the real problem, if the price for not estranging Italy was Abyssinia, they were ready to pay that. The French needed all their divisions in the north and not defending the south against an Italian threat.

The French officials included Leon Noel, Secretary General of the French Government, who was later to write a book “Les illusions de Stresa” and one of the conference’s most interesting delegates , the head of the French Foreign office, Alexis Leger.(also known by his pseudonym , Saint-John Perse) , who as well as his considerable diplomatic background was a well-regarded poet. While Secretary to the French Embassy in Peking in the early 1920s, Leger took the opportunity to go off wandering in the Gobi Desert and wrote an epic poem “Anabase”. Well known in Parisian intellectual and artistic circles, he was a friend of Macel Proust . While in Washington in 1921 at the Disarmament conference he had been recruited as assistant to French Prime Minister Aristide Briand, becoming his chef de cabinet in 1925 and participating at the Locarno Conference. Leger managed to get “Anabase” published in 1924 , but then gave up publishing poetry while serving as a diplomat. In 1930 TS Eliot published an English translation of “Anabase”. In 1932, Leger became the Secretary General of the French Foreign office. A firm believer in the international order and the League of Nations, his main aim was the construction of pragmatic and realistic alliances with powers that could help France stop Nazi Germany, so with Fascist Italy and Soviet Russia.

On the 11 April, the Italian hosts left Isola Bella again for the landing stage in Stresa, after being greeted by the usual band, which struck up “Giovenezza” , they were taken by car to the station to await the arrival of the British delegation. The Orient Express arrived promptly at 8,35 and the British were met by a guard of honour from the 54 fanteria. At the station Mussolini proffered a friendly welcome to MacDonald and the British delegation. There was actually no particular love lost between the men, back in 1924 , MacDonald had been a prominent critic of Mussolini regarding the murder of Italian Socialist MP, Giacomo Matteotti, Mussolini still bore a grudge. Vansittart was pleased that Suvich and Aloisi were in the reception party, he reckoned that they were plausible and he could do business with them.

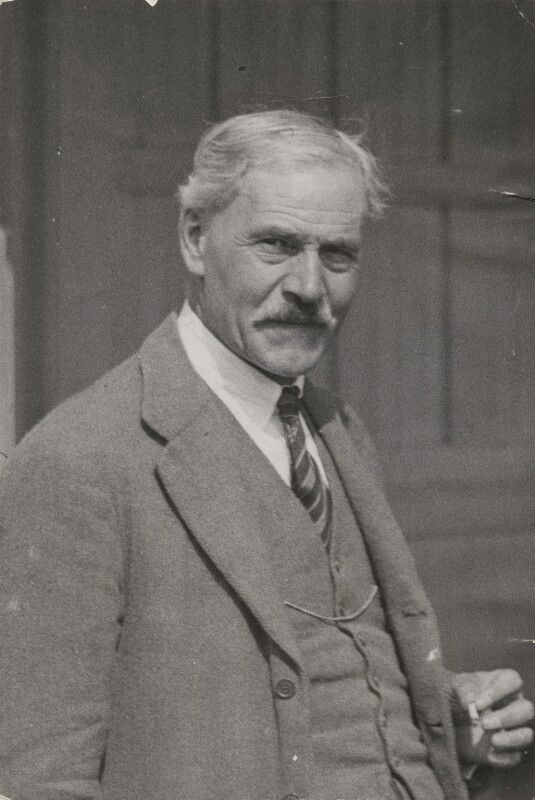

Ramsay MacDonald he was probably suffering from dementia during the Stresa Conference

MacDonald had met Mussolini before during a trip Rome after the 1934 disarmament conference in Geneva. Sir John Simon had been present on that occasion and had subsequently held another meeting during a Christmas holiday in Capri. Unfortunately by April 1935, MacDonald was in a fairy sorry state, his health had suffered after an operation for glaucoma, and he had undergone a couple of breakdowns, he was suffering from depression possibly linked with the fairly advanced stages of senility. In the House of Commons he had become renowned for his rambling and generally incoherent speeches. The consensus seems to be that he should have resigned as Prime Minister two years earlier in 1933, instead he stayed on too long and in the end undermined his own reputation. Neither MacDonald nor Simon was any match for the vigorous 45-year-old Italian dictator. At one time during the Stresa Conference, MacDonald’s interpreter failed to understand one of his by now familiar incoherent and rambling discourses and made up his own version of the speech. Worst of all MacDonald apparently failed to read any of his briefing papers, or at least understand them. According to Leon Noel, MacDonald was “tall distinguished looking , self-assured and vain “ but that “His mental faculties were being to fail him “

The Music Room at the Palazzo Borromeo site of the conference

The trouble was that MacDonald, considered himself an expert in Foreign Affairs , as such he had keep Sir John Simon who was regarded as a deeply mediocre Foreign Secretary in place. In the National Government , MacDonald was heavily dependent on the large Conservative Majority , but did not particularly wish to see a more competent and more activist Foreign Secretary if they were a Conservative. So despite not being very good at the job , Simon was in place for as long as MacDonald was. In an essay on Simon, the British politician and historian Roy Jenkins, considered that as a lawyer Simon was “much better at analysing a problem than solving it” Neville Chamberlain complained that Simon was constantly seeking instructions from the Cabinet rather than imposing his own consistent policy on it. He also gave the impression of reading from a brief . Simon’s reputation had taken a nosedive when at a speech to the League of Nations following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, rather than giving a forceful condemnation of Japanese aggression, he had equivocated and more or less presented the Japanese argument for the invasion. The speech which offended almost everybody apart from the Japanese led to Simon being labelled the “Man of Manchuria”. Roy Jenkins quotes Chamberlan ( again ) as saying “he has certain air of -what is it- shyness, which is rather disconcerting in a man of the first rank “Jenkins reckoned that Simon was “deficient in the qualities needed of a powerful and successful minister” and that “Simon was often the despair of his officials , went before the Cabinet without knowing his own mind, had a solution forced on him by others, and perhaps not unnaturally in the circumstances defended weakly in public”- Leon -Noel regarding Simon “ as breaking every record for hypocrisy and underhandedness” He was possibly the worst Foreign Secretary until very modern times. So the British delegation in Stresa was headed by a seriously unwell Prime Minister who appeared to be suffering from senile dementia and a decidedly second-rate Foreign Secretary.

Sir John Simon possibly Britain's worst Foreign Secretary -well at least until 2016

It was fortunate that , MacDonald and Simon had an entourage of competent advisers, although it seems questionable whether they were listening to them or not. Perhaps the most important was Sir Robert Vansittart , Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs- the most senior civil servant in te Foreign Office. The old Etonian Vansittart, had entered the Foreign Office in 1902, starting as a clerk in the Eastern Department, where he was a specialist on Aegean Islands affairs. He was an attaché at the British Embassy in Paris between 1903 and 1905, when he became Third Secretary. He then served at the embassies in Tehran and Cairo until 1911, he was appointed to the Foreign Office. During the First World War he was joint head of the contraband department and then head of the Prisoner of War Department under Lord Newton. He took part in the Paris Peace Conference and became an Assistant Secretary at the Foreign Office in 1920. Like Basile and Leger, Vansittart also had literary pretensions having published several volumes of poems, plays and novels, the last being “Pity’s Kin” in 1924, By January 1930 he had risen to Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, where he supervised the work of Britain's diplomatic service. At the Foreign Office in the 1930s, Vansittart was a major figure in the loose group of officials and politicians opposed to appeasement of Germany. Vansittart argued that there Like was no prospect of a "general settlement" with Hitler, and the best that could be done was to strengthen ties with the French in order to confront Germany. The Foreign Office team also comprised Horace Seymour, Principal Private Secretary to the Foreign Secretary who had been a First Secretary at the British Embassy in Rome in the 1920s and Clifford John Norton, Private, Secretary, Vansittart’s two senior officials. They were accompanied by the lawyer Herbert William Malkin , Senior Legal Adviser to the Foreign office and William Strang. Head of the League of Nations Section of the Foreign Office,

Sir Robert Vansittart-Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

Also in the British Delegation were Ralph Wigram , Head of the Central Department of the Foreign Office , who had been briefed on Foreign Office assessments on the growing strength of the Luftwaffe and Wing Commander Charles Medhurst, Deputy Director Air Intelligence , of the Royal Air force and who knew a thing or two about the Luftwaffe . Wigram had been a rising star at the British Embassy in Paris, where tragically in 1926, he had been struck down by polio. It had been touch and go whether he would live, let alone return to work. He survived and returned to the Embassy, although now using a stick and callipers to walk. In 1933, he had returned to London to Head the Central Department of the Foreign Office which dealt with Germany. His long experience in Paris had made him sensitive to French insecurities and having read “Mein Kampf” he was now convinced that there was little prospect of peace in Europe while National Socialism ruled in Germany. One of Wigram’s main concerns was the rearmament of the Luftwaffe. Together with Vansittart and Michael Cresswell, a secretary at the Foreign Office , Wigram began to assemble a mass of detailed information on German rearmament . Wigram was so concerned with the situation that, with Vansittart apparent blessing he began to leak information to Winston Churchill, at that time out of government. Wigram had meet Churchill at Chartwell in March 1935, and it appears that from April he began to copy Foreign office documents on the subject and supply them to Churchill . Churchill visited Wigram at his home in North Street and at the Foreign Office and Wigram visited Churchill in Chartwell . It was all technically a breach of the Official Secrets Act but given their concerns on German strength Vansittart and Wigram regarded it as justifiable.

One of key issues was that the Air Ministry and the Foreign Office disagree about the potential strength of the Luftwaffe. Between 1933 and 1935, the Luftwaffe had been bult up in secret in contravention of the Versailles Treaty. In March 1935, Hitler revealed the secret to the world. The Air Ministry and the Foreign Office already disagreed on predictions for the size of the Luftwaffe. The Foreign Office now began to distrust the Air Ministry’s estimates which they regarded as to conservative, especially as to when the Luftwaffe would achieve parity with the Royal Air Force. Hitler was quite happy to play along with British beliefs that the Luftwaffe was singers that it really was. The British were obsessed with the idea of huge German bomber fleets reaching London and counting planes, when in fact many of the Luftwaffe’s planes were designed for tactical support of the army rather than strategic bombing as Blitzkrieg tactics were later to prove. Anyway the ir Ministry and Foreign Office adopted positions of mutual distrust which were coming to a head just as the Stresa Conference took place.

Against that background , as soon as the British delegation left on the boat train from Victoria Station, Wigram and Medhurst got talking about German air power. They were soon joined by Vansittart and Rex Leeper of the Foreign Office News Department. Vansittart and Wigram noted that Medhurst shared their concerns and persuaded him to try and raise the matter of air power with the Prime Minister. Medhurst felt a bit uncomfortable about this , being of rather junior rank to speak directly to the Prime Minister. But he agreed to try and do so.

Once the British had arrived in Stresa and settled in , Vansittart appreciated the location

“the hotel was good, hospitality lavish , and each morning we were ferried across the lake to meetings in the Borromeo Castle on the heavily guarded Isola Bella. Everything was well managed, Italian Spring perfectly timed , Mussolini’s chameleon ego at it most colourful. The only imperfection was the difficult in reaching decisions, “

In Vansittart’s view everybody had a different agenda. “The Italians were out to save Austria, the French to secure Eastern Europe, but the British people cared for none of these things” To the British in 1933, Mussolini was still seen as a potential friend or even ally. The elephant in the room was Ethiopia. Anthony Eden had warned Sir John Simon that Mussolini should be warned against any Italian intervention in Abyssinia. Vansittart advised Sir Eric Drummond to press this point on MacDonald and Sir John Simon. And they should warn Mussolini of potential British wrath should he attack Abyssinia . Vansittart’s strategy was to negotiate a agreement with Mussolini on Europa and then tell him it would be void if he intervened in Abyssinia. Instead everybody preferred to just dodge the issue. Even Vansittart did not press for any discussion on Abyssinia. Neither did Drummond, MacDonald or Simon. , although they had apparently promised Anthony Eden they would do. One of the expert advisers Geoffrey Warner heard from Italian Foreign Ministry Officials that an Abyssinia adventure was on the cards. He warned Simon over breakfast and Simon still, did nothing.

The British delegation to Stresa, included Geoffrey Thompson of the Foreign Office’s Egyptian Desk , Thompson had never been to Abyssinia but had been involved in the discussions with the Italians since the Wal Wal incident. While the Ministers discussed European Affairs, Geoffery Thompson did get the chance to have informal discussions with his two Italian counterpart, Giovanni Battista Guarnaschelli. The Head the Ethiopian Desk of the Italian Foreign office and Leonardo Vitetti from the Italian Embassy in London. Thompson had already met Vitetti several times at the Foreign Office in Lindon. The three men met at Stresa on 11 April. Thompson told the Italians that the Foreign office was disturbed by rumours of possible military action by the Italians in Abyssinia. Thompson and Guarnaschelli and Vitetti met again the afternoon.

If the conference had any tangible effect it might have been a breakfast discussion which finally put Britain on a path to rearmament, Wing Commander Medhurst did get his breakfast with Ramsay MacDonald and managed to put forward the Foreign Office view on Luftwaffe Rearmament . Following MacDonald’s return from Stresa he authorised an immediate expansion of British Air Power, which led in May 1935, to the adoption of Plan C, which envisaged an expansion of the Metropolitan (UK based ) Royal Air Force .

During the conference some of the delegates were taken by boat across the lake to Pallanza pay their respects at the mausoleum of General Cadorna . A reminder of when Italy , France and Britain were wartime allies. Podesta Basile also got his place in the limelight, taking a party of delegates around te Isole dei Pescatore.

Throughout these informal discussions , the subject of Abyssinia was never raised . Vansittart had no opportunity to raise the matter with Mussolini and MacDonald and Simon failed to do so. It might have been a perfect opportunity to do so, Sir Robert Vansittart is attributed some of the blame. Sir Eric Drummond and Vansittart subsequently engaged in a war of words on the subject. Although the unofficial talks took place no explicit warning was given to Mussolini , if he had not yet decided to invade Abyssinia , a strong warning at Stresa might have dissuaded him, the Labour politician Hugh Dalton called it “one of the most criminal blunders in the whole of British diplomacy”.

France wanted to have a resolution approved in which it was stated that a next violation would be punished with sanctions. Mussolini thought this to be the minimal action one could take and wanted more definitive agreements in order to guarantee the independence of Austria. MacDonald acts as a defence on behalf of the viewpoint of Hitler because he did not intend to hinder Germany. This seems the world upside down: the British as the advocate of the Nazis and Mussolini as the accuser. Finally a vague commitment had been agreed to no longer accept any further violation of the Treaty of Versailles.

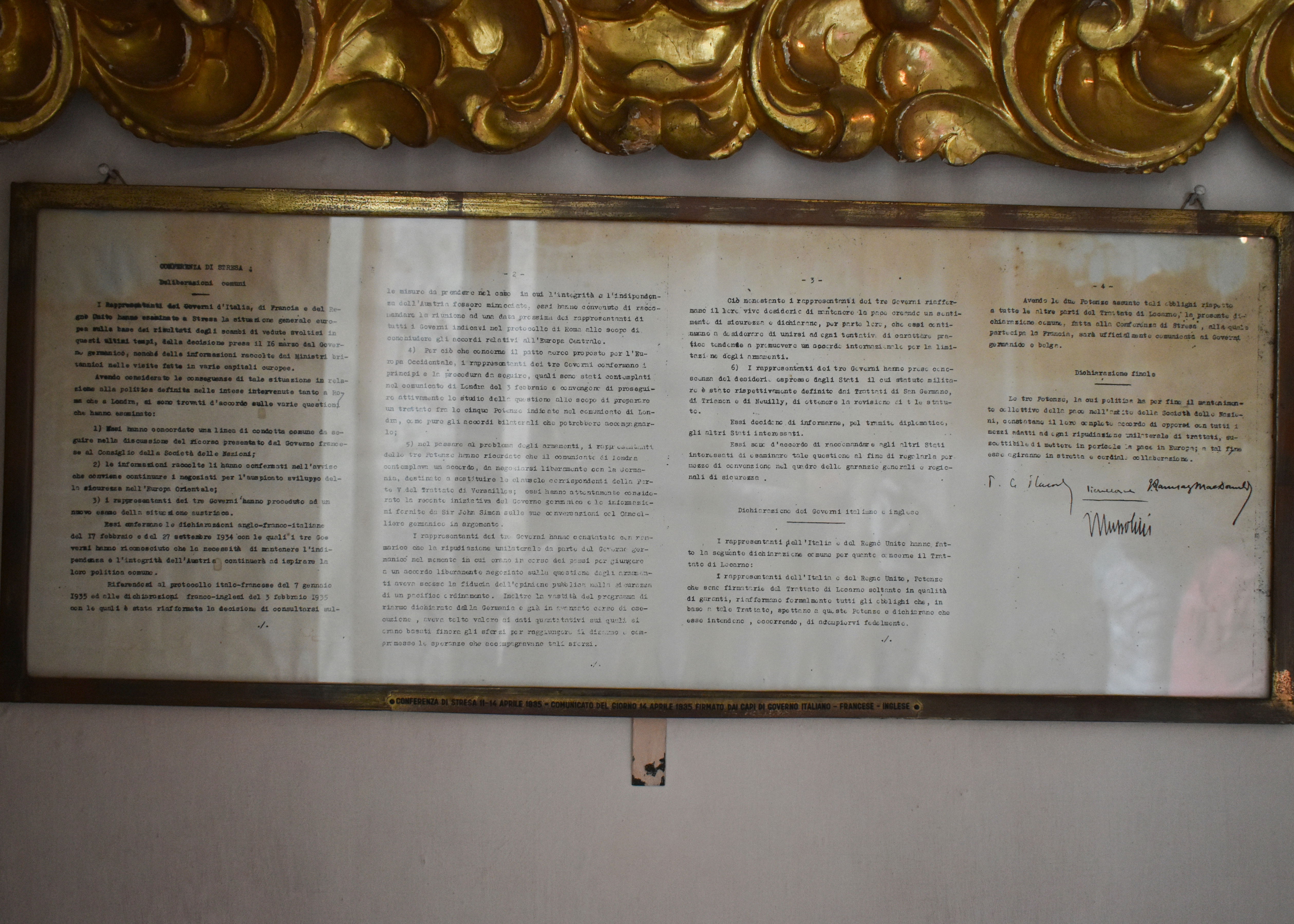

Copy of the Stresa declaration signed by MacDonald, Flandin and Mussolini

A few months later the coalition of Stresa fell apart as Great Britain signed a fleet agreement with Germany on 18 June, without informing their allies of Stresa. The agreement allowed Germany to build up a fleet which would have no more than 35% of the capacity of the British fleet and an equal number of submarines. This agreement was in flat contradiction with the Treaty of Versailles and in fact an encouragement of the rearmament of Germany. As Sir Robert Vansittart put it :

“With this fiasco we lost Abyssinia, we lost Austria, we created the Axis, and we made the coming war with Germany inevitable.”

The Italians invaded Ethiopia in October 1935 and in 1938 the Anschluss took place. The failure of Stresa was total.

Further reading and sources

The Mist Procession. The autobiography of Lord Vansittart

Available to borrow on archive.org

Vansittart : Study of a Diplomat by Noman Rose

Available to borrow on archive.org

France and the Nazi Threat : the collapse of French diplomacy 1932-1939 by Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste,

Available to borrow on archive.org