Death beyond the Front Line-the British at Arquata and Cremona and the Spanish Influenza

Previously, I have been off looking at the Front lines for the British Army in Italy at Montello on the Piave and on the Asiago plateau. In order to supply the two British Army Corps at the frontlines and to evacuate casualties, the British also developed a considerable infrastructure in the rear areas. Supplies were landed at the port of Genoa and the British built a large base Depot at Arquata Scrivia, some 20km from there to hold men and supplies ready for the frontlines. They also established General and Stationary hospitals in the rear areas at Cremona, Genoa and Bordighera to allow for the evacuation of casualties. Even away from the frontline, life was not entirely safe for the British soldiers, as the number of casualties from rear-echelon units buried in Italian graves attests. Apart from the day-to-day accidents with equipment and ammunition, in October 1918 the Spanish Influenza was running in Italy and caused a substantial number of deaths.

The Base Depot at Arquata

When the British first considered sending military assistance to Italy, they began to study potential transport routes to the Peninsula and locations. In December 1916. Brigadier- General John Henry Verinder Crowe, late of the Royal Artillery in East Africa and of the British General Staff had been sent to Italy to reconnoitre potential sites for a British base in Italy and had determined on Arquata as being a suitable location . Despite having spent the previous few years commanding the Royal Artillery in the war in German East Africa, Crowe was also a former instructor in military Topography at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich which presumably equipped him to choose a good site for a Military Base. By the time the official report of the Convention in the Event of Cooperation of British Troops in Italy was signed in May 1917 the British General Staff had already identified Arquata as the location far the British Base in Italy ( should it be required) .

Arquata Scrivia, is a comune (municipality) in the Province of Alessandria in Piedmont, about 100 kilometres southeast of Turin and about 35 kilometres southeast of Alessandria on the left bank of the Scrivia river. It is set in a valley, surrounded by wooded hills . The name derives from the Latin arcuata (arched), due to the presence of an aqueduct supplying the nearby Roman town of Libarna. Arquata is mentioned as a castrum (fortress) in the 11th century, and later was contended between the Republic of Genoa and the commune of Tortona: after they signed a peace in 1227, they dismantled the castle. In 1313 it was given by emperor Henry VII to the Genoese Spinola family, who were named marquises of the town in 1641. It was sacked by French troops in 1796. The following year it was annexed to the Ligurian Republic. After the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte, it became part of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont. Then nothing much happened until at the end of 1917 the British Army arrived in town.

Once British cooperation had been decided on following the Italian debacle at Caporetto, the Army Council decided to send supplies to Arquata ahead of the British Divisions being sent. They determined that Arquata would the site for :

One Army Service Corps ( ASC ) Base Depot, Mechanical Transport Base Depot, Auxiliary Petrol Company, Central Requisition Office, Base Pay Unit, Base Post Office, Advance Medical Stores Depot, Motor Ambulance Convoy, Two sanitary sections, Two casualty Clearing Stations, General hospital, stationary Hospital base supply depot, Field butchery, Field bakery, Line of Communications supply company, Veterinary hospital , Base depot veterinary stores, Chief Ordnance Officer and base establishment ,two companies army Ordnance Corps, Base provision office. Ordnance mobile workshop,

The Base had to be big enough to service an Army, which was supposed to reach a strength of five divisions or around fifty to sixty thousand men. Arquata was well located for British supplies arriving from France, both by railway and sea. It was served by a double line railway, running up from the port of Genoa, and indirectly from the port of La Spezia, for supplies arriving by sea. Troops arrived from France by train, down the Rhone Valley to Marseille and then along the Cote d’Azure crossing the frontier at Ventimiglia from where they either marched or took the single line railway along the Italian Riviera to Savona, from where they were able to connect with the Italian rail network. Others took the alternative route through the Alps Mont Cenis to Modane, where they detrained and marched to Susa to connect with the Italian Railways.

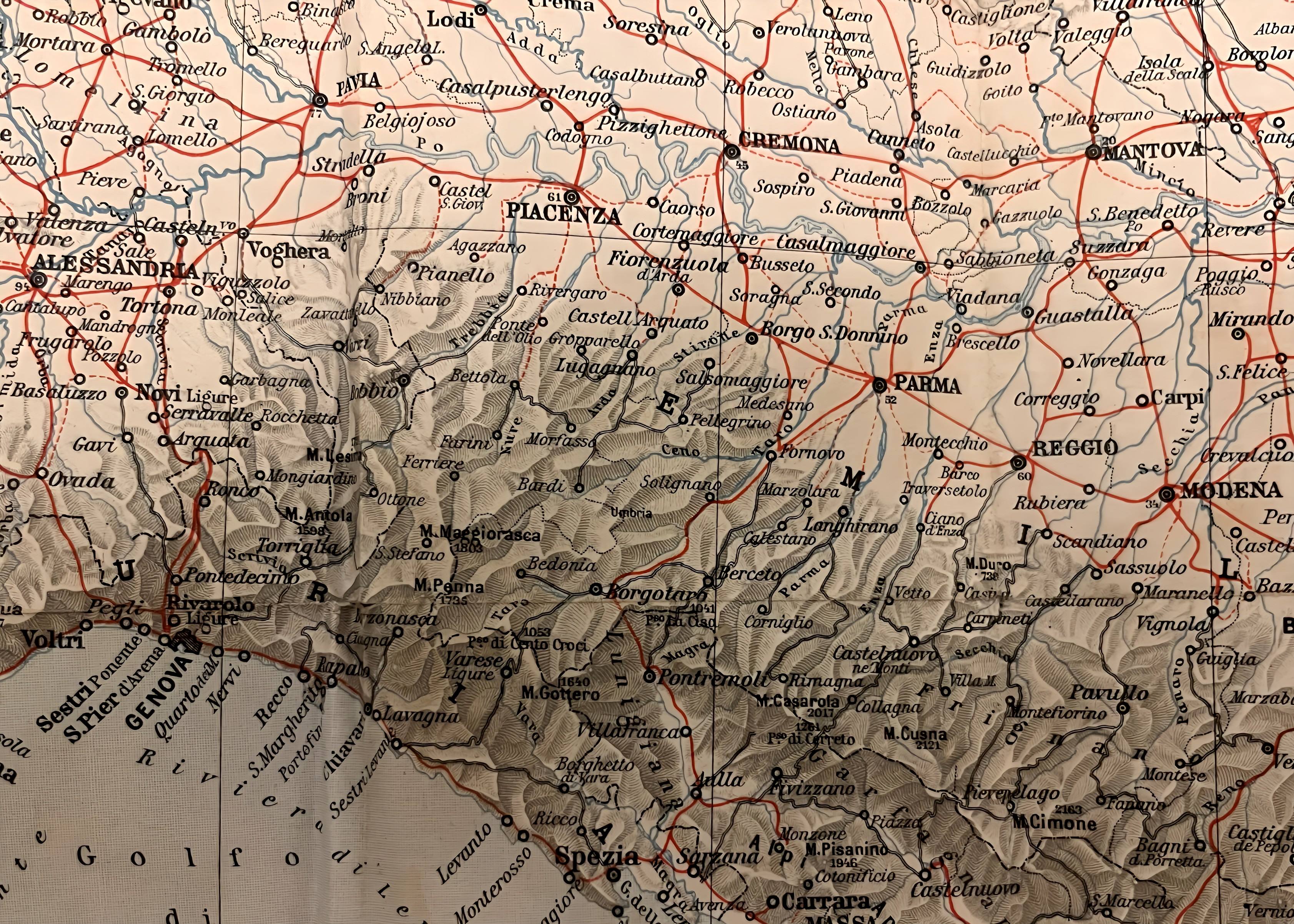

The Italian railway network in the early 20th Century. The railway lines are in red. Secondary routes connected Genoa to the Base Depot at Arquata and then to Tortona, Voghera, Cremona and Mantova

One of the big advantages of Arquata, was that it kept the British away from the heavily used railways between Turin and Milan and the Italian frontlines, which were in constant use transporting Italian troops and the war material being produced by the heavy industries of Turin and Milan. To avoid this bottleneck , the British sought an alternative route . Although they were not main railway lines, Genoa connected with Arquata and then through Tortona, Voghera , Stradella , Piacenza and Cremona to the concentration area for British Troops at Mantua, where the British Divisions would detrain. After the disaster at Caporetto, the British envisaged the Italians retreating all the way back to the River Mincio and having to hold the line there. In the event the Italian retreat stopped at the Piave River and the British troops had to march from Mantua to the frontline. Arquata was then well positioned for the sending of troops to the concentration area for the British Divisions around Mantua and on to the frontlines. Of course, nobody mentioned it but it was also conveniently close to Genoa and the sea, were the Italian Front to collapse totally.

The Base at Arquata functioned as a smaller replica of the huge British base at Etaples in France, assembling reinforcements and war materiel for the front in Italy. Reinforcements were sent to regiments in Italy by the Deputy Adjutant-General , 3rd Echelon in Rouen, and to Arquata before going on to their units posted at the front. From January 1918, after passing through Arquata, they were sent to a holding area at Torreglia nearer to the front at Padova.

The Royal Engineers established a Base Depot at Arquata, with an Advanced RE base at Padova. Ordnance stores were established, again with advanced depots nearer to the front at Padova. Equally vital was the Base Motor Transport Depot, which had located its forward depot near to Cremona.

It should not be forgotten that the British Army still relied heavily on horses. The ASC Remounts Service was responsible for the provisioning of horses and mules to all other army units. It was not a large part of the ASC, despite the huge numbers of animals produced, amounting in 1914 to only four Remount Squadrons that ran four Remount Depots (Woolwich, Dublin, Melton Mowbray and Arborfield).Animals were obtained during the war by compulsory purchase in the United Kingdom and by purchasing from North and South America, New Zealand, Spain, Portugal, India and China. Three remount squadrons had been sent from France to Italy and their depots were formed at Cremona in and Pavia. ( 10,19 & 33 Remount Squadrons). Remount squadrons would have consisted of approximately 200 men and 500 horses. Generally the men in Remount squadrons tended to be older and more experienced, perhaps with a background in horse care. ( Certainly two men from the 19th Remount Squadron, buried at Arquata, were in their 40s). Horses, of course , needed vets and the Army Veterinary Corps established a veterinary hospital at Voghera, close to Arquata and a more advanced Veterinary hospital at Cremona ( no 1 and 22. Veterinary Hospitals)

The British Central Command at Arquata was in the Palazzo Spinola, now the Town Hall

For the welfare of the troops , there were originally bakeries at Arquata which were later moved to the two British Corps areas. ( 24 and 25 Field Bakeries) There was a Canteen and various welfare facilities. In the end the British virtually took over the small village , the Central Command for the Base was in the Palazzo Spinola in the town centre. The 15th Century Chiesa di Sant’Antonio was used as a tobacco and grocery shop for British troops . the building of the Società Operaia di Mutuale Soccorso became the House of the British Soldier.

The Chiesa di Sant’Antonio was used as a tobacco and grocery shop for British troops

The Società Operaia di Mutuale Soccorso became the House of the British Soldier

Herbert Warner Allen , a British journalist had been the Paris correspondent of the Morning Post , in 1914 he had been appointed an official representative of the British press at the French Front. In 1917, he accompanied the British Expeditionary Force to Italy. In 1920 he provided the text , which accompanied the paintings of Captain Martin Hardie in the book, “Our Italian Front”. Allen visited Arquata on several occasions . His first visit was only a few weeks after the force had departed for Italy. He described the ordered camps of tents all over the fields surrounding Arquata with no bustle or disorder and each man doing precisely what they were supposed to do

A Martin Hardy watercolour of Arquata in 1918

The same view today

“The Base station was crammed with men and trains to all appearance it was chaos, but I soon had evidence that order prevailed”…….

“The stores dump was admirably tidy. Heterogeneous objects of every kind were stacked on a disused railway siding as if they had all been set out by an expert window dresser. Barbed wire , wheel barrows, trench tools, rolls of felt , wire netting , timber in every shape and form , weird apparatus required for aerial photography , in fact every conceivable kind of material was stored so as to be easily and immediately available. “

Allen found the British and Italian working cooperatively together, although he did lament the organisation of Italian railways . He returned to Arquata in 1918, when he found that the original village had almost disappeared beneath colossal piles of material and that the Italian shop signs had disappeared to be replaced by English notices. By 1918

“there was abundance of everything that the army could need . Trains were no longer hours late, and illusive trucks no longer disappeared in the mysterious way which had once rejoiced the hear of Italian railway officials."

Allen was gratified when an Italian officer likened the British Army to the 10th Legion which had “ risen from the grave and returned to Italy” . (An allusion to the Roman 10th Legion which had taken part in Caesar’s first invasion of Britain. . Maybe the 9th Legion, which according to legend might have disappeared somewhere on Britain’s Northern Frontier in the 110s was more apt . Whichever Roman Legion , it was a nice thought anyway.)

Cremona

As well as planning to send supplies to the front , the British also established a number of medical facilities in rear areas of Italy to evacuate casualties away from the front. From initial studies Cremona in Lombardy was considered to be the most suitable location for an advanced hospital, being on the line of any potential British retreat in the event of the enemy breaking through the Piave Front and in the event of heavy casualties being suffered, it represented a shorter journey by Ambulance Train from the front. Cremona was also accessible by Motor Ambulances.

Number 29 Stationary hospital was relocated from Salonika and by the beginning of December 1917, it was up and running in Cremona and providing hospital accommodation for 600 cases.

The school in via Realdo Colombo, Cremona which housed the 29th Stationary Hospital

The rear of the school in vias Realdo Colombo

The hospital was located in a school building in via Realdo Colombo in Cremona, about 10 minutes walk from the Duomo and central square and not far from the railway station where the ambulance Trains arrived. The 29th Stationary Hospital was joined later buy the 30th Stationary Hospital which also moved from Salonika. . The two stationary hospitals in Cremona would have had a capacity of around 800, with around 170 staff

The Number 11 General hospital and number 38 Stationary Hospital from France were established in Genoa. The Number 11 General Hospital occupied the Miramare Hotel , conveniently near to the Railway Station and with an imposing view of Genoa Harbour; The hospitals in Genoa had capacity for around 1800 patients, with around 470 staff in total

The Miramare Hotel, Genoa. Formerly Number 11 General Hospital

At the beginning of 1918, number 51 Stationary Hospital also arrived in Italy, being spread between two sections in Genoa and a Hospital at the Base Depot at Arquata .

Dorothea Matilda Taylor acted as Principal Matron in Italy for Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Nursing Service, , she therefore got to visit all of the British hospitals at the front and in the Rear areas of Italy and left some interesting portraits of them.

Genoa

“There was one General and two Stationary Hospitals at Genoa. The first in a large hotel, the others in schools. Two of them already had patients and the other was being put in order. As there was no heating in the hotel, the building was intensely cold; it was, however, a very fine hotel with a marble staircase and beautiful baths, though at the time the baths were of little use, as there was no hot water. In the schools were some stoves which the patients thoroughly enjoyed. Later on we had an Infectious Hospital at Genoa, also a very nice hostel for sisters coming from the United Kingdom or moving about the country.”

Arquata

Shortly after I arrived, I went to Arquata (which was the Base), where there was a nice little hospital close to the railway. The building had originally been a wine factory and was compact and workable. The nursing staff consisted of the matron and sisters, who were attached to the Artillery unit, and who had been in the retreat. They had lost all their kit and possessions and were spending their off-duty time in making cotton dresses out of grey material purchased in the village. Arquata is a most beautiful spot, standing very high and surrounded by mountains. There was deep snow on the ground that day, and it was not at all certain that we would be able to cross the pass on our return journey. In spring and summer Arquata was a perfectly ideal spot, and the wonderful wildflowers there were a constant joy to us, while the sunsets were both grand and impressive.

Cremona

Shortly after, I journeyed north to Cremona, where there were two Stationary Hospitals, both in schools. It was when arriving in Cremona in the early hours of the morning – on account of a bad breakdown with the car – that we were received by an Italian soldier who spoke English with a very strong Glasgow accent. He was employed as interpreter at the Sisters’ Mess. He had been born and brought up in Glasgow, where his father, an Italian ice-cream vendor, had married a Glasgow woman; but the Matron explained that he was not of great use as an interpreter as he hardly knew any Italian. There was deep snow on the ground, and it was snowing hard when we went round the hospitals later in the day. A large convoy was arriving at the station, and every one was very busy. The hospital was full, and there were beds in all the corridors.

Reduction in numbers

In February 1918, The British considered withdrawing two divisions from Italy and consequently whether the number of men at Arquata could be reduced. A report of the time gives some idea of the numbers who were there at the time. The base supply deport consisted of 18 officers and 386 other ranks – which the report considered may be possible to reduce by 4 officers and 60 men. It was deemed essential to keep the Base Motor Transport ( MT) Depot at it‘s current level, although there may have been some scope at reducing the Advanced MT deport where 6 officers and 220 men were based) . it was thought possible to reduce the number of Remount Squadrons by one, while still leaving the two remount depots open, and also to reduce the number of places at the veterinary hospitals from an establishment of 3250 places to 2000, which would have freed about 400 soldiers in total. It was forecast that in the event of a reduction in the number of divisions , the 30 Stationary hospital at Cremona and the 66 General Hospital could be moved, while still leaving circa 4000 hospital beds for the estimated 70,000 British troops who might remain in Italy ,,

The Spanish Flu

Find the site of a former British General or Stationary hospital or a Casualty Clearing Station and unfortunately you do not have to look far to find a CWGC cemetery and Arquata and Cremona are no exceptions. Both have small CWGC plots in the Municipal Cemeteries. Surrounded by the imposing and baroque structures which the Italians seem to favour as tombs, you find the neat rows of identical British headstones, The striking thing about both Arquata and Cremona is the number of British soldiers who died far from the frontline from disease. Many battlefield casualties died at the Casualty Clearing Stations near to the front line and are buried near to where they fought on the Asiago Plateau or near the Piave River. A handful survived long enough to die of wounds at Arquata and Cremona, However the vast majority of casualties in both cemeteries died in October and November 1918 and from one particular disease. the Spanish Influenza.

The CWGC cemetery in the Arquata Municipal Cemetery

CWGC Cremona

British troops in Italy had been suffering from influenza throughout the summer of 1918 The first epidemic had struck in June 1918, the official history reports that ;

“In May , soon after sun-helmets had been issued, a great epidemic of influenza, as in other parts of the world, raged among the British troops in Italy. The attack usually lasted three days and recovery was quick; but the disease was so widespread that as many as thirty percent of the strength of a division might be out of action when it was at is worst. “Gargling” was the prescribed prophylactic. The epidemic continued into June, but by 1st July . Lord Cavan was able to report that the influenza had practically vanished.”

Even the Prince of Wales, who was serving in Italy on the Staff of Lord Cavan, was struck down by a fever, presumably the flu. On 3rd June 1918, he wrote to Mrs. Freda Dudley Ward,

“I’ve been in bed all day with a touch of fever… whether it was the effects of bathing I don’t know, but anyhow, I began to feel very seedy at tea at the Club at Sermione ( sic) & so we motored back here at once & I went to bed with temperature of 100 degrees! Today it has been 101 degrees…. It’s the prevalent disease throughout the British Forces, Italy just now, though it does not last long as a rule!!!!”

Captain Edward Brittain serving with Sherwood Foresters , also mentions the problems being caused by influenza on the Asiago Front This first wave of influenza may have had some influence on the initial British setback on the Asiago Front. The two British divisions on the frontline, the 23rd Division and the 49th Division, were suffering heavily from the influenza epidemic and were substantially below the establishment levels. The 48th Division, which had recently returned from the rear suffered the most. On 13 or 14th June, some 800 influenza cases admitted to hospital on 13th and 14th June, while 1,500 had already been evacuated. It was not just the men in the trenches, headquarters and Brigade Staffs were also severely depleted and six out of twelve infantry battalions were commanded by Majors. When the Austro- Hungarians attacked in the morning, they initially broke through the thinly spread British lines- although the British troops later rallied and held their ground. That was the first wave of the Spanish Flu, most of those who fell ill recovered , however, when the disease returned again in September 1918, it was far worse.

By the end of September 1918 the flu returned to Arquata. In August there is only one casualty buried at Arquata, but suddenly at the end of September 6 men die and then in October and November, 27 and 12 men have died.

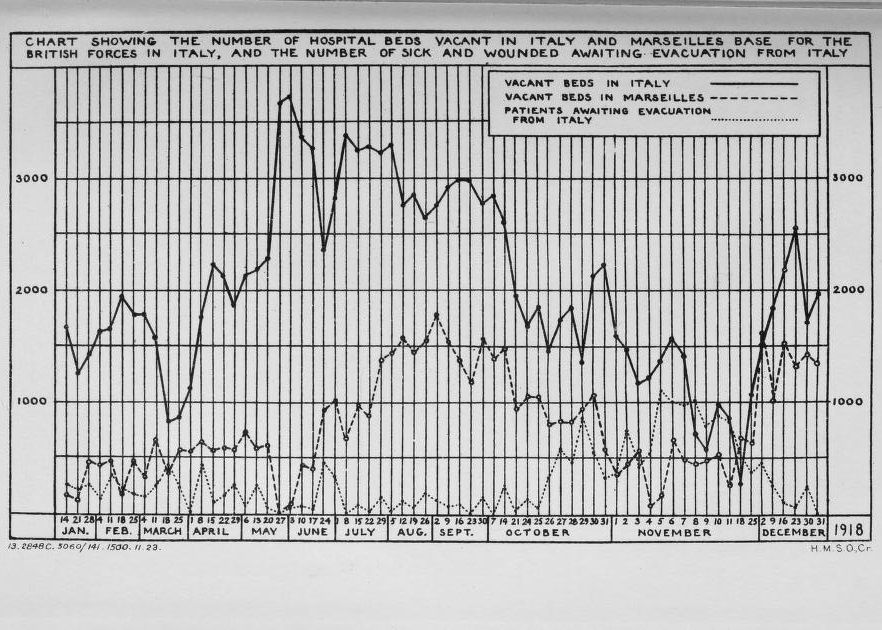

To some extent the spread of the influenza can be seen from the cart below, showing the vacant hospital beds in Italy. These reach a peak at the end of May 1918, which was a period of relative calm in the Italian Front, The number of vacant beds falls in June with the onset of the first influenza epidemic and the Austrian offensive of 15 June 1918. July through to September are relatively quiet and then following the fresh outbreak of influenza in October , the number of vacant beds falls dramatically until it reaches a minimum around 11 November. This is not wholly attributable to influenza, the offensives from 24 October on the Piave also account for the fall. Also notable are the number of casualties awaiting evacuation from Italy which peaked in October and November, Again these may also be attributable to battlefield casualties,

The History of the Medical Services in Italy reports the following;

“The weekly wastage from sickness, however, was never excessive until October and November 1918, when it increased to an alarming extent on account of the epidemic of influenza. An outbreak of this disease had already occurred in May and was continued in June, but appeared to have abated in July. At first it was thought to be sand-fly fever, and Lieut. -Colonel P. J. Marett, R.A.M.C, an expert in this disease, was ordered from France by the War Office to investigate it. A convalescent camp was established for the patients at Grumolo by a field ambulance of the 48th Division. Lieut-Colonel Marett reported that the disease was not sand-fly fever, although no very clear indication of its nature was elicited at the time.

When it recurred in October it was definitely of the nature of influenza, and this disease was the cause of most of the admissions to casualty clearing stations during the time the British were in Italy. During the thirteen months ending December 1918, 10,590 cases had been admitted. The admissions for no other disease approached this figure ; inflammation of the connective tissue and diarrhoea, which was specially prevalent in August, only giving 3,727 and 3,485 admissions respectively, and pyrexia of uncertain origin 2,754.”

CWGC Cemetery Arquata

A similar pattern can be seen at the CWGC Cemetery Cremona. As noted above, Cremona was well out of the way of the frontline and was the site of two stationary hospitals and a Remount Depot. Therefore, one would expect to see a number of casualties who had been evacuated down the casualty evacuation chain and who have died of wounds. But then 38 men died in October 1918, followed by another25 in November. In October ten of the dead were from the locally based Remount squadrons, and another nine from other Logistics units ( the ASC, the Ordnance, and the Lines of Communications troops – The Royal Munster Fusiliers ).

After the Armistice

On 4 November 1918, the Italians signed an armistice with the Austro- Hungarians at Villa Giusti,, near Padova and the war on the Italian Front was over. British troops began to leave Italy. By 15 January 1919, around 10,000 men had already left the country and from then on around 650 per day were leaving . By 3rd March, there were only 6512 men remaining in a mixed Brigade, and 4296 in Lines of Communication Units mainly at Arquata. In the end it was decided to leave 4 battalions in Italy ; the 1/7th Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the 8 Yorks & Lancaster, the 22 Manchester and the17th Gloucestershire, together with various Logistics and support units

The Armistice did not mean an end to the casualties. On 23rd November, the 8 Yorks & Lancaster were sent to Fiume , where they remained until September 1919 as an occupation force. The 8 Yorks & Lancaster were commanded by Lt. Col Stuart Lumley Whatford CMG, DSO. Stuart Whatford was born in Eastbourne on July 23rd 1879. He was first commissioned on January 15th 1902 and saw service in the Boer War. At the onset of the Great War Captain Whatford was adjutant to the 3rd Yorkshires and in April of 1916 was appointed second in command of the 22nd battalion of the Durham Light Infantry. He saw action on the Somme with the DLI and was then appointed to the command of the 8th battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment. . Promoted to lieutenant colonel in January of 1919 he then returned to the command of the York and Lancasters in February of 1919. He was killed in a car accident between Cremona and Mantua on August 30th 1919 aged 40, presumably either on the way to or coming back from Fiume.

Having survived the war, Lt. Col Stuart Lumley Whatford was killed in a traffic accident on the way to or from the British forces occupying Fiume in NE Italy. Six times mentioned in despatches, he was awarded the DSO and clasp, French Croix du Guerre and Italian Croce di Guerra

A brother officer in the Yorkshire Regiment wrote,

“His alluring personality and inspiring influence will ever remain as a landmark in the annals of the Yorkshires and every one of us were the better for coming into contact with him”.

The 1/7th Warwick’s and 22 Manchester remained at Arquata from April 1919, until at the end of May they were sent to Egypt. By then , few British troops remined in Italy clearing up, disposing of surplus stores, and maintaining the Taranto/ Cherbourg line of Communication, which was still being used to bring troops and demobilized men back from the Middle East. On 28th June 1919, the British GHQ in Italy was closed. By December 1919, only 180 officers and 2100 other ranks remained in the country. The British base at Taranto was closed on 16th December. In the end the base at Arquata was closed and by 15 April 1920, all living British troops had left Italy.

The War Cemeteries

Arquata was one of the last cemeteries in Italy to be finished. The local municipality were not keen on its location, felling that by ceding the land in perpetuity to the British, it might interfere with the future growth of the town. In the end they agreed and the separate part of the Municipal Cemetery in via Vapore was the last First World War Cemetery in Italy to be finished. On 14 May 1923, His Majesty King George V, who had been on a state visit to Rome, made a pilgrimage to the British Cemeteries on the Asiago Plateau and the plains below. He never made it to Arquata, but at the same time that the commemorations were being held 200 miles to the East in Asiago, the citizens of Arquata staged their own commemoration to the British guests who had died in their town. A procession marched out of the town to the cemetery, it was headed by the Mayor of Arquata, Luigi and the mayors of nearby Serravalle and Novi, there was an honor guard of the 43 Infantry Regiment whose band accompanied the march. At the cemetery, the mayor laid a wreath.

As noted the majority of the burials at Arquata were from there rear -echelon and logistic units. Of the 94 burials. 29 are from the Royal Army Service Corps, 12 from the Ordnance Corps, 11 from the Royal Engineers, 3 from the RAMC and 2 from the Veterinary Corps. Additionally, another 6 were from the 1st Garrison Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers who were assigned to protect the British Line of Communications in Italy. The remaining 22 dead came from Line Regiments, judging by their dates of death some died passing through Italy before the British became engaged in the fighting, a number died after the Armistice.

Even further from home than most of the casualties at Arquata was Private D Richards of the 6th Battalion, British West Indies Regiment. The 6th Battalion was raised in Jamaica through voluntary recruiting between November 1916 and March 1917. After basic training at Swallowfield Camp, Jamaica the battalion sailed from Kingston on 30 March on HMS Breton. No sooner had it left than there was an outbreak of measles on board, the sick were landed in Martinque and St Lucia, where many of them died. The battalion arrived at Brest on 19 April 1917, where there was more sickness with at least ten men dying from measles and pneumonia,. They were transferred to Belgium, around Poperinghe and Vlaminghe where they sustained a number of casualties. In January 1918, the 6th Battalion was sent by train from Belgium to Marseille and then down through Italy to Taranto. There they spent four months working on the quays, unloading military supplies from trains and loading ships bound for the British forces in Salonika and the Near East.. In April 1918, they were sent back to France, where they were engaged in manual labour in the area of Fresselles. At the end of October they were ordered back to Taranto again, boarding the train at Rouen on 6 November, back down to Marseille, along the cost of Italy and then down the peninsula by rail. Private Richards never made it to Taranto , he was presumably taken ill on route and left in the hospital at Arquata, where he died of sickness on 24 November 1918.

Private D Richards (7195) , 6th Battalion, British West Indies Regiment, Son of Thomas and Susan Richards of Cumberland, Williamsfield , Jamaica.

The biggest killer becomes starkly apparent , after muddling along at 1 or 2 per month , there is a sudden spike in deaths in October and November 1918, which was when the febbre spagnolo or Spanish Influenza hit Italy at its worst. For those deaths occurring after hostilities and the flu pandemic had ceased the majority seem to come from the ASC ( RASC) , specifically from the 1034th Mechanized Transport Company.

Sapper James Tayne from Leeds, husband of Margaret Tayne died of influenza at Arquata, 8 November 1918

Private John James Cooper ( R4/063683) of the 19th Remount Squadron of the RASC, died at Arquata on 17 November 1918 from pneumonia. Husband of Rose Elizabeth Cooper of Ampthill.

The pattern in Cremona Municipal Cemetery is the same. Here there are 85 British graves tucked away in a corner of the Monumental Cemetery. Of these 22 were members of the Army Service Corps, of whom 10 were members of Remount Squadrons, five were Royal Engineers and two from the RAMC. The remainder were from British line Regiments and Artillery Units stationed in Italy. Following the same pattern as Arquata, 38 of the deaths were in October 1918 and 26 in November. In total 75 percent of all the deaths at Cremona were in those two months. Cause of death is not recorded on the headstones , bit in some cases the CWGC records do record a cause of death and these were overwhelmingly from influenza or pneumonia.

In fact it is rare to find many casualties at Cremona who died of wounds, one exception was Private Albert Gardiner of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment who is recorded as " died of wounds" on 29 October 1918. The 2nd Warwicks had been involved in the assault on Grave di Papadouli in the Piave on 23/24 October, Several soldiers from the 2nd Battalion who died in the assault are buried at Giavera British Cemetery near to the frontline ,, presumably Albert Gardiner was wounded and survived long enough to be evacuated to the stationary Hospital at Cremina,

Private Albert Gardiner died of wounds and is buried in at Cremona Cemetery

Among those who are recorded as having died of influenza, was Lance Bombardier James Gilliland from Belfast serving with V Anti Aircraft Battery of the Royal Garrison Artillery, attached to the British GHQ he died at 29th Stationary Hospital in Cremona on 2 November 1918,

Lance Bombardier James Gilliland, died of the influenza and is buried in Cremona

Whatever their unit and whatever the cause of death there is no doubt that all the men buried in Arquata and Cremona did their bit towards the defence of Italy in its hour of need.

Gallery of the CWGC Cemetery Arquata

Gallery of the CWGC Cemetery Cremona

The Watercolours of Martin Hardie

Sources and Further reading

Our Italian Front: by Allen, H. Warner (Herbert Warner) ; Hardie, Martin, London 1920

Official History of the Great War: Military Operations Italy 1915-1919. The Naval and Military Press