Holocaust Memorial Day 2021- the Stolpersteine of Milan by David Roberts

This week in the commemorations regarding Holocaust Memorial Day, the Comune of Milan is starting to unveil a further 31 Stolpersteine around the city to add to the 90 already present. Stolpersteine, in English literally means Stumbling Stones – in Italian they are called “pietri d’inciampo”. They are small brass cubes embedded in the pavement outside the places which were the residences of people who were deported to Nazi concentration camps in the period after the Germans occupied Milan in September 1943. The stones are the idea of German artist, Gunther Demnig and there are now thousands of then placed in European cities.

In 1943 a web of terror enveloped the city with its nexus at the Nazi Headquarters in the city, the notorious Hotel Gestapo in via Santa Margherita , a few hundred meters from La Scala. In 1943, the Germans took over the liberty style Hotel Regina and turned it in to the HQ of Aussenkommando, from where they held absolute power of life and death over the city. Two other notorious locations were the San Vittore prison, where a special Jewish wing was created to hold prisoners detained in Milan and the surrounding areas and Binario 21 (Platform 21) of Milan’s Central Station where the prisoners were taken to a hidden underground platform and herded into cattle trucks headed for Nazi Concentration Camps. Some trains went direct to Auschwitz, some went to the Italian transit camp at Fossoli , and when that was overrun by the Allies, to another transit camp in Bolzano. Wherever they went they met the same fate. Some of the Jewish victims had made it as far as the Swiss border before being detained and sent back, others who were old and infirm had stayed on in Milan in the forlorn hope that they would be of no interest to the Nazi occupiers. It is also important to note that the deported commemorated by the Stolpersteine were not only Jews, but also the citizens of Milan who had been involved in strikes, anti-fascist activities or in some cases individuals who were just caught up in the Nazi’s web of terror.

This year the commemorative ceremonies are likely to be a low-key affair, due to the restrictions imposed by the COVID19 emergency. Before the lockdown started, I had visited most of the existing stolpersteine in Milan. It was an interesting way to see different parts of the city, from the former working-class areas around viale Monza and Loreto to the wealthy areas of the city centre. The victims came from all walks of life. I now must visit the remaining few, I did not get to previously and the new ones. Here is just a sample of the Stolpersteine and the stories behind them. Since it is Holocaust Memorial Day, I have here concentrated on some of the Jewish victims, except for one non-Jew, an extremely brave Italian prison guard who paid the ultimate price for helping the prisoners in the Jewish wing of San Vittore.

Via de Togni is an upmarket residential street just off the Via San Vittore, not far from the Museo Scientifico Leonardo da Vinci and from the church of Santa Maria della Grazie (home of the Cenacolo) and indeed the prison. Four Stolpersteine commemorate the members of the Reinach family; Ernesto Reinach, Ugo de Benedetti, Etta de Benedetti Reinach and Piero de Benedetti.

Ernesto Reinach was born in Turin in 1853, his family had emigrated to Italy from Prussia, In 1882, the young Ernesto funded a company in Milan, Ernesto Reinach Lubrificanti which produced industrial lubricants. As the Italian automobile industry developed, the company branched out into automotive lubricants, especially with the name “Oleoblitz”. It soon became famous, the company-s publicity began to appear on Touring Club of Italy maps, it was the official lubricant for the legendary Marque of Isotta Fraschini. Oleoblitz became associated with the great early years of Italian motorsport, with Alfa Romeo, with Motorcycle raids and the Targa and the early days of Italian Aviation, sponsoring the first meeting of Italian Aviators at the newly opened Taliedo Aerodrome ( just outside Milan) in 1911. Reinach’s daughter Maria Antonietta (“Etta”) married at noted Turin lawyer Ugo de Benedetti who moved to Milan where he developed a name as lawyer to some of the best known Italian commercial and industrial groups. They had two sons, Giancarlo and Piero.

By autumn of 1943, the family must have been feeling unsafe in Milan. The Reinachs had a country villa at Lanzo d’Intelvi in the hills above Lake Como, from where you could literally walk into Switzerland from the back garden. Other members of the family had already safely crossed into Switzerland using that route. They were helped by the custodian of the Villa, Giuseppe Grandi. While the Fascist gangs of Milan collaborated with the Nazi occupiers and did substantial amounts of their dirty work, ordinary Italians like Grandi shine out as a beacon of hope. In the end he paid with his life. For helping persecuted Jews cross into Switzerland, he was denounced, arrested by the Germans, and died at Buchenwald.

Ernesto Reinach and family packed up the big old Isotta Fraschini and set off for Lanzo. They made it as far as Torrigia a small town on the shores of Lake Como from where the road goes up into the hills towards Lanzo. They were literally less than hour from freedom when they were arrested by a German patrol. They were taken back to Milan to San Vittore Prison. On 6 December 1943, they were taken to Binario 21 of Milan Central Station. They were walked through the doors and into the underground platforms where the convoys were assembled. Once loaded onto a cattle truck, the truck was lifted to the station platform where the train was assembled, Convoglio n.05 left Milan Central Station for Auschwitz. 88-year-old Ernesto Reinach died en route. Etta Reinach de Benedetti, Ugo de Benedetti and 15-year-old Pietro de Benedetti arrived at Auschwitz on 11 December 1943. They were most probably gassed immediately on arrival. Piero’s brother Giancarlo was not with the family, he had been receiving treatment at a medical institution and was not with them when they left Milan. In the end with the help of family friends and some benevolent Italians, he was eventually smuggled across the border into Switzerland and safety.

Not far from via De Togni, via De Amicis is in another wealthy part of Milan, not far from Sant’Ambrogio and Cattolica University. Here are commemorated, Michelangelo Boehm and Margherita Luzzato Boehm.

Born in Treviso in 1867, Michelangelo Boehm graduated in engineering from the Polytechnic of Milan. He married Margherita Luzzato and they had three children. The family lived in the comfortable residential street of Via De Amicis. Michelangelo Boehm had assisted the Italian War effort in World War in producing gas supplies. In 1928 he was appointed a lecturer at his alma mater the Polytechnic and nominated as the Italian Vice-president of the International Gas Union in 1932. At the 2nd Conference of the IGU in Zurich in 1932, he presented a paper on “The use of electricity in the manufacture of Town Gas”. The official banquet was at the Grand Hotel Dodler and delegates toured the Zurich gasworks. In 1935, Boehm received one of Italy’s highest honours being appointed an Officer of the Crown of Italy. In 1938, Italy’s Racial Laws ended Boehm’s long and distinguished career. He was no longer able to teach at the Polytechnic, his honours were removed. He and Margherita retired to the Valssasina above Lecco, hoping they were too old for anybody to bother with them. Meanwhile their children had fled to Switzerland. In December 1943, the elderly couple decided it was time to go. Unfortunately, they were arrested not far from the Swiss border at Tirano, taken to Tirano prison, then to Como, then to San Vittore prison. There, they were separated. Margherita was sent to Fossoli di Carpi and Michelangelo being over 70 was released. His freedom did not last long, he was rearrested in Milan on 29 January 1944 and the next day was sent to Binario 21 at Milan Central Station to join Convoglio N. 12 for Auschwitz. The train arrived at Auschwitz on 6 February 19944, Michelangelo was probably gassed immediately on arrival. Margherita was held at Fossoli until 22 February 1944 when she was also sent to Auschwitz, being gassed on arrival on 26 February 1944.

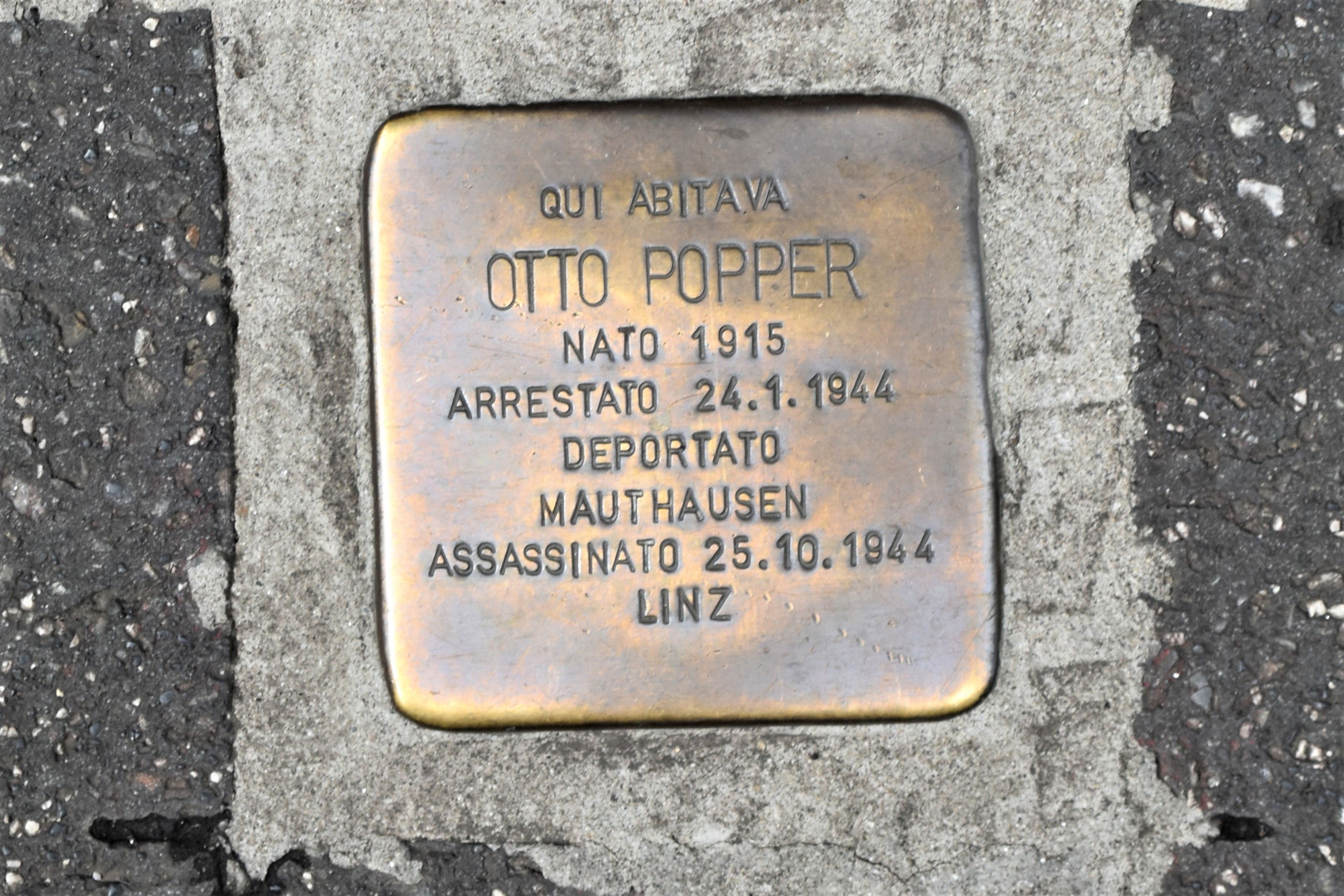

Many of the Stolpersteine are a bit off the beaten track and may take some finding. But the visitor to Milan easily see the stone commemorating Otto Popper at via Mengoni 2 , literally five minutes’ walk from the Galleria and the piazza della Scala.

Otto Popper was born in Vienna, Austria on 6 October 1915 with a Jewish father and gentile mother. He graduated from the University of Vienna in Jurisprudence in 1938, then after the Anschluss he moved to Milan. He lived right in the centre of Milan at via Mengoni and set up a prosperous import export business with Ing. Giuseppe Speroni and others. Arrested in December 1943. Popper was used by the Germans as an interpreter in San Vittore prison. He took full advantage of that role to pass messages to the outside and bring messages in, as well as parcels of provisions. His friend and colleague, Speroni continued to provide help from the outside. In the end Otto was deported from San Vittore to Mauthausen, from there he was sent tone of the sub-camps in Linz. He died of pneumonia at the sub-camp of Linz III on 25 October 1944. His wife Arianne Dufaux had escaped to safety in Switzerland after his arrest together with their two sons. The youngest son was born while Otto was in San Vittore Prison, so he never saw him. For his heroic work in helping the prisoner, Otto was known as “The Angel of San Vittore”.

Milan’s Jewish population was highly cosmopolitan, not only consisting of refugees from Eastern Europe , but also from Italian Jews who had moved to the Levant and returned to Italy. The Silvera family ( Lelio Silvera, Bahia Laniado Silvera and Violetta Silvera) are commemorated outside their apartment at viale Monte Rosa 18, the long road that leads out of the centre of Milan towards the San Siro Stadium.

Leilo Silvera and Bahia Laniado, were born in Aleppo, Syria when it was part of the Ottoman Empire. Both were members of Italian expatriate families and held Italian nationality. Aleppo, located on caravan routes from the Far East and Near East to the Mediterranean, had long been a trading entrepot. The city had provided a refuge for many Sephardic Jews when they were expelled from the Spanish dominions. Later Italian Jewish traders, particularly from Livorno began to establish links with the city. In many cases the younger sons of Livorno based merchants were sent to Aleppo on buying trips and in some cases they stayed there and married into local Jewish families. After the collapse of the Ottoman empire, the Silvera family moved to Milan, where Leilo Silvera was in the textile exportation business. One of their sons Salmone went to Egypt to study, while the rest of the family stayed in Milan.

On 2 December 1943, Leilo and Bahia together with their 19-year-old daughter Violetta were detained at Porto Ceresio on Lake Lugano from where they were attempting to flee to Switzerland. In researching these stories, I visited Porto Ceresio. It is a pleasant little lake side town at the end of a railway line from Milan’s Porta Garibaldi Station. On a sunny day, The views across Lake Lugano (also known in Italian as Lake Ceresio) are stunning . The Swiss border is around half an hours walk from the town centre, with a frontier crossing on the lake side road . It is tragic that the Silveiras got so close and yet were so far from salvation, stepping out of the railway station they would have been able to see Switzerland, unfortunately they never made it. After passing through prisons in Varese and San Vittore, they were deported to Auschwitz where they are believed to have been sent straight to the gas chambers on 6 February 1944.

All of these victim of Nazi-Fascist persecution passed through Milan’s San Vittore Prison and it is near here at piazza Filangeri 2, that we find a Stolperstein, for a non- Jewish victim, the heroic prison guard Andrea Schivo.

Andrea Schivo was born on 17 July 1895 in Villanova d’Albenga ( Savona). He fought for Italy in the First World War on the Piave Front and was wounded. Because of his war service, after the war he was appointed as a Prison Guard at Imperia, then transferred to Milan to the San Vittore prison. After 8 September 1943 he was assigned to the Jewish wing controlled directly by the SS. To the best of his abilities Andrea tried to procure extra food for the Jewish detainees and to pass messages between them and their families. This was a dangerous activity in a prison controlled by the SS. In the end he was caught by an error, the SS guards found a piece of chicken bone in the Jewish wing – where such food would never have been given out. Andrea was arrested and locked up in the same prison where he worked. On 17 August he was transferred to the transit camp at Bolzano and from there to Flossenbürg where he died on 29 January 1945. On 13 December 2006, Andrea Schivo was recognised by Yad Vashem as one of the ”Righteous Among Nations”. The following 21 September, he was posthumously awarded the Medaglia d’Oro al Merito Civile alla Memoria , by the President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano. The Italian Prison service renamed their Training School in his memory and a primary school in Villanova d’Albenga was named after him. Sometimes it takes the Italians a while to getting round to doing the right thing, but they do in the end.

Most of the material above comes from the excellent publication by the Comune of Milan CAS gennaio 2021 Pietre_d_Inciampo A5.indd (musvc2.net). I supplemented this with some of my own research. Truly all involved in the project deserve a vote of thanks for preserving the memories of those who might otherwise be forgotten.