Mr Chamberlain changes trains

Currently on Netflix is the film “Munich. The Edge of War” The film based on Robert Harris’s novel “Munich” is a fictionalized account of the Munich Conference in October 1938. Jeremy Irons, gives a fine performance as a rather sympathetic Neville Chamberlain, which should go some way to rehabilitating his reputation. At least among a younger generation of film watchers. After Munich, Chamberlain then continued to put in the miles in the search of peace, while buying time for an eventual British rearmament

In January 1939, Chamberlain travelled to Rome for talks with Italian Prime Minister, Benito Mussolini. Whereas he famously flew to Munich and back, for his Rome trip he made the 900 mile train tip from Paris. Chamberlain was reluctant to give up on a hope of detaching Italy from the Germans and wanted to bolster the undoubted anti-German sentiments in Italian Military and business circles. The British called (without being invited), they wrote, they sent flowers and in the end on 10 June 1940, Mussolini’s Foreign Secretary (summoned the British Ambassador to Italy and handed him the ultimate “Dear John letter”, in the form of Italy’s declaration of war on Britain and France.

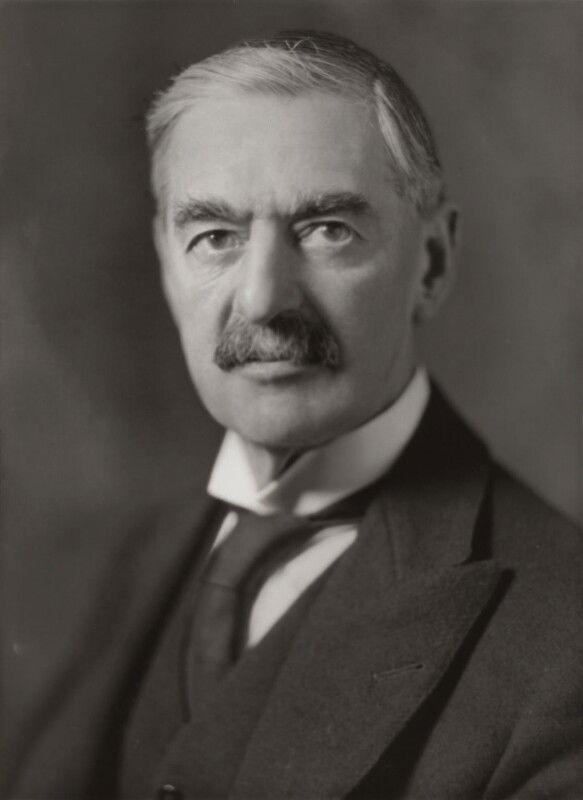

Neville Chamberlain

At 68 Chamberlain became the second-oldest person in the 20th century to become prime minister for the first time. He was widely seen as a caretaker who would lead the Conservative Party until the next election and then step down in favour of a younger man, probably Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. The trouble was that Eden resigned on 20 February 1938 in protest at Chamberlain's policy of coming to friendly terms with Fascist Italy. Eden used secret intelligence reports to conclude that the Mussolini regime in Italy posed a threat to Britain, while Chamberlain was using his sister-in-law Isabel (widow of his half-brother, the former Foreign Secretary Austen Chamberlain) as a secret channel for discussions with Mussolini. Despite his inexperience of the international and diplomatic scene, Chamberlain had a clear idea of what he wanted to do. And that was to keep Mussolini neutral and separate the Italians from the German Camp.

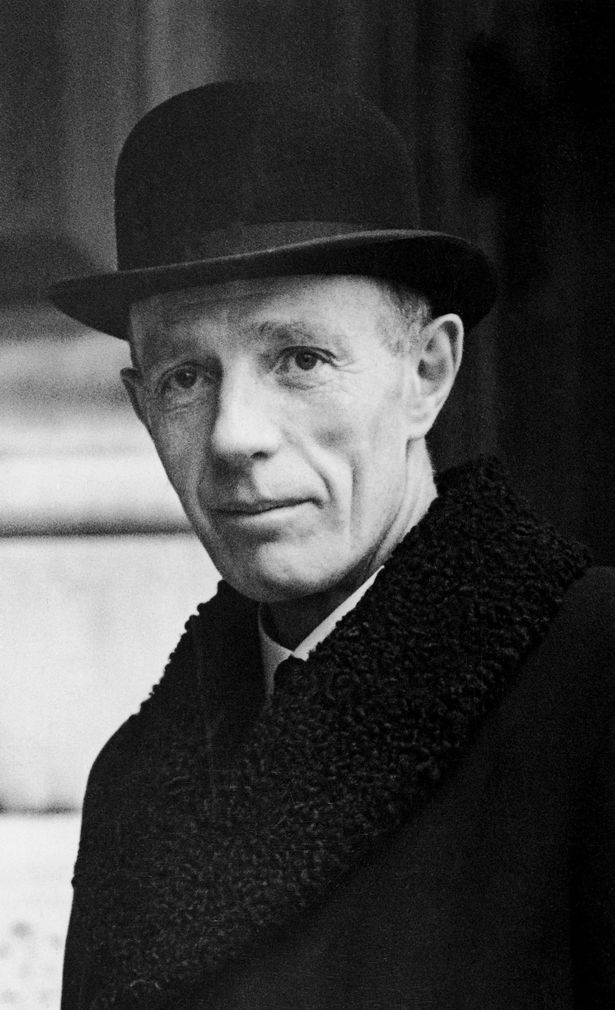

Following Eden’s resignation. Lord Halifax became Foreign Secretary, he was almost a decade younger than Chamberlain, In the First World War he was sent to the front line and in 1917 he was Mentioned in dispatches ("Heaven Knows What For" he wrote). All this despite only having one hand. He was then deputy director of Labour Supply at the Ministry of National Service from November 1917 to the end of 1918. Halifax then went to be Viceroy of India, where he survived several assassination attempts. Halifax was appointed Foreign Secretary on 21 February 1938, despite criticism that so important a job was being given to a peer. Chamberlain preferred him to the neurotic an excitable Eden: "I thank God for a steady unruffled Foreign Secretary."

Lord Halifax

Chamberlain together with Lord Halifax and a high-powered delegation of British officials took the night Paris to Rome express on 10 January 1939. It is not possible to identify all the officials who accompanied them, but the principal members of the team included:

Osmond Somers Cleverly, the Principal Private Secretary to the Prime Minister (educated at Rugby School and Magdalen College. Cleverly had served in WW1 in India and Mesopotamia before joining the War Office in 1919. In 1935, he had been appointed PPS to Stanley Baldwin and then to Chamberlain.

Osmond Cleverly

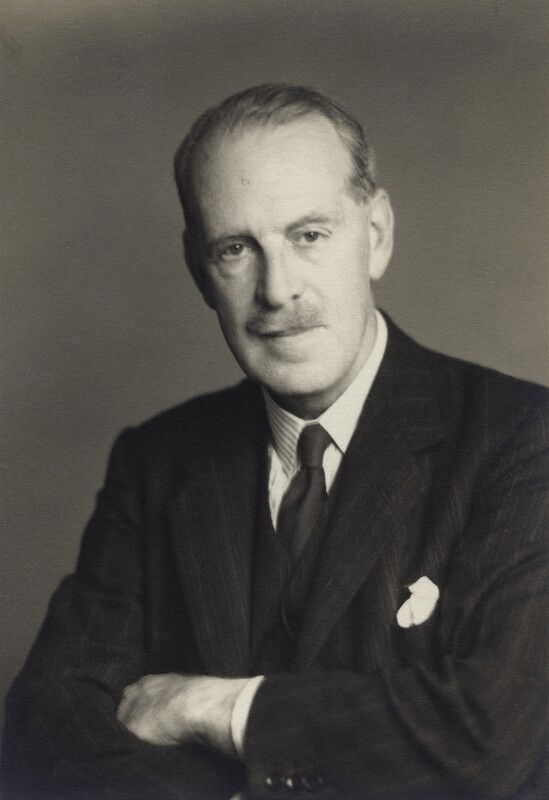

Alec Cadogan (Eton and Balliol College, Oxford) Cadogan had a distinguished career in the Diplomatic Service, serving in Constantinople, Vienna, and during the First World War, at the Foreign Office in London. Following the war, he had served at the Versailles Peace Conference. In 1923, he became the head of the League of Nations section of the Foreign Office In 1933, Cadogan accepted a posting at the British legation in Peking, where he met with Chiang Kai-shek and attempted to persuade him of Britain's support. Despite the lack of a real Chinese government, Cadogan did his best but lacked support from the Foreign Office. In 1936, Cadogan returned to London as Deputy Under-Secretary to Anthony Eden. In 1938, Cadogan replaced Robert Vansittart as Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office.

Alec Cadogan

Alec Douglas Home ( Lord Dunglass) was Chamberlain’s Parliamentary Private Secretary, basically his right-hand man and liaison officer with the Parliamentary party and the back benches. Having worked so closely with Chamberlain for many years, Home knew him better than most, despite describing him “as by no means easy to get to know” with an abrupt manner that stemmed from shyness rather than rudeness. He was essentially a very solitary man. But there was another side to Chamberlain. Home says,

“When he did unbend, he was a fascinating companion., for in the lonely years he had taught himself everything there was to know about birds, butterflies and flowers; and his observations of them were accurate and scientific and his enthusiasm infectious. Music too was one of his delights. Fishing and shooting wee hobbies which he enjoyed. “ ù

But according to Home, for the most part Chamberlain kept that attractive side of his personality well hidden behind his forbidding exterior with the black hat, stiff collar, dark clothes and umbrella.

Maurice Ingram (Eton and King’s College, Cambridge) had served in the War Office during WW1 before joining the diplomatic service. Between 1926 and 1934 j had been chargé d’affaires in Berlin and then moved to China. Between 1935-37, he had served as chargé d’affaires in Rome before returning to the foreign office as Head of the Southern Department.

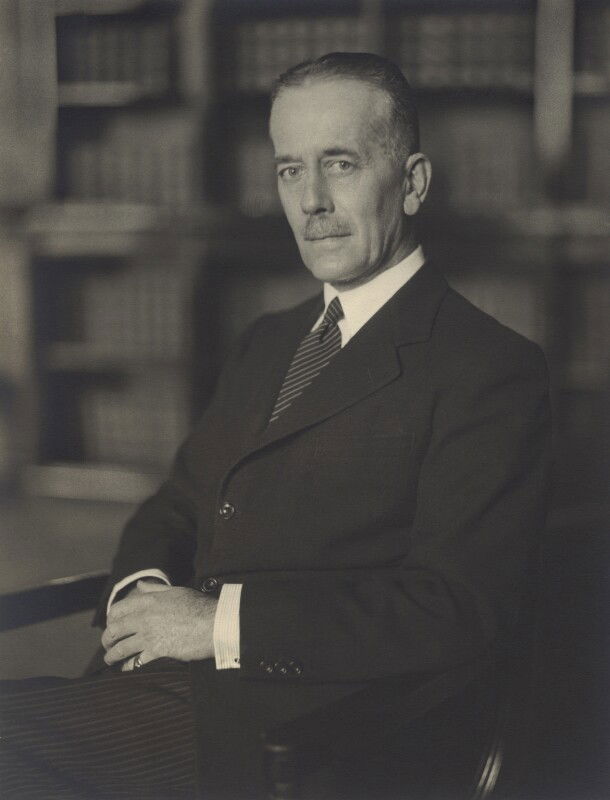

Oliver Harvey, PPS to Lord Halifax had also previously served at the Rome Embassy (from 1922-192() before moving to Athens, returning to London as PPS to Anthony Eden and subsequently Halifax.

Oliver Harvey

In charge of Press arrangements was Charles Peake, a veteran of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment in WW1, he had joined the Diplomatic Service in 1922 working in Sofia, Tangier, Tokyo and Washington before being appointed to the Foreign Office Press department.

The importance Chamberlain placed on his mission, seems to be reflected by the fact that he assembled a team which included men, who knew something about Italy and had spent time there. British relations with Italy had been poor for years following the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, Italian intervention in the Spanish Civil War (particularly the sinking of merchant ships by Italian submarines) and the Italian’s generally poor relations with Britain’s Ally France. The British did go to Italy to negotiate anything in particular- in fact it appears that they had almost invited themselves- the main aim was to iron out a few remaining areas of contention ad to talk to the Italians. Chamberlain’s hand -picked team of “experts” were experienced in all these issues.

The British party set out from the Gare de Lyon the gateway to the South. The “Rome Express” consisting of long sleeping cars, a dining car, and two luggage vans, one containing a bathroom waited their departure.

Paris Gare du Lyon from where the British delegation departed on the evening of 19th January 1939

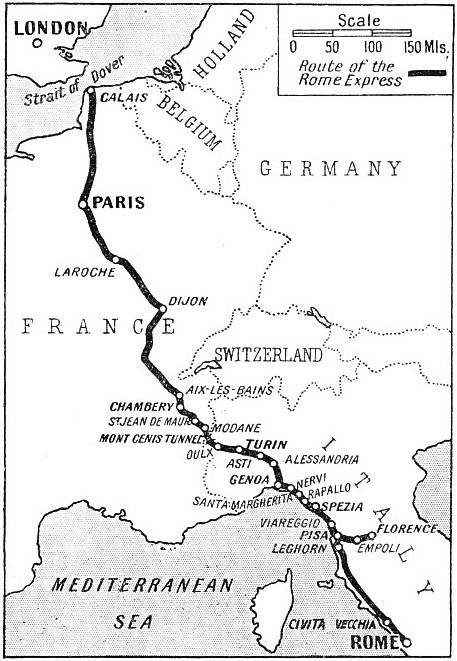

Ahead of them was a 900 mile train journey to Rome

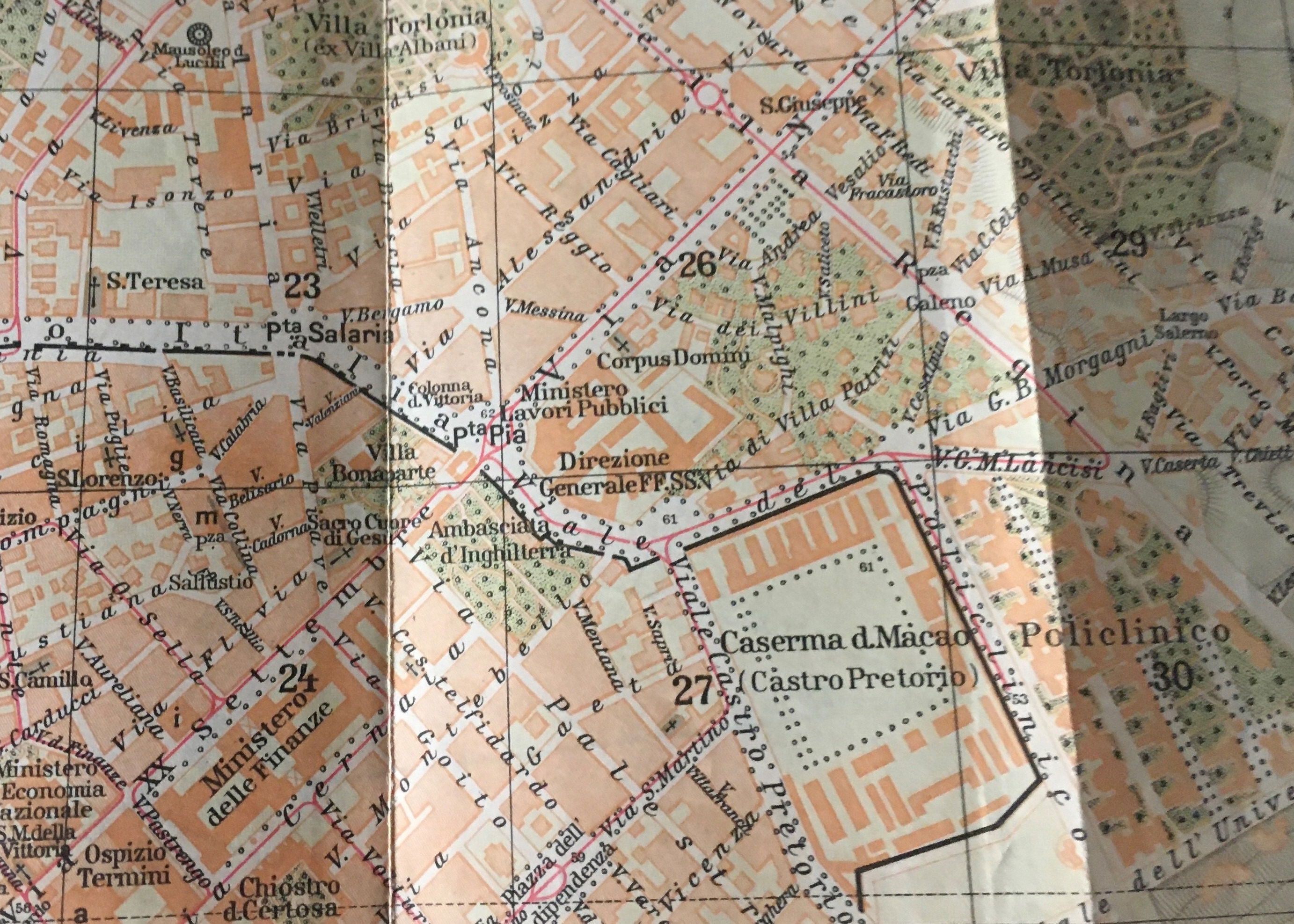

"Omnes viae Romam dicunt "- the route of the Rome Express""

The British party set out from the Gare de Lyon the gateway to the South. The “Rome Express” consisting of long sleeping cars, a dining car, and two luggage vans, one containing a bathroom waited their departure.

Leaving at around 8.20 dinner was available in the restaurant car and by the time the serving had finished the train was hurrying through the darkness of Central France in a long, easy swing to Dijon which was reached twenty-two minutes after midnight. From Paris to Laroche, a “Pacific” locomotive was used, on the next stage, to Dijon, in view of the long climb to Blaisy-Bas Summit, a powerful 4-8-2 was normally substituted. Haulage between Dijon and Chambery was then entrusted to a 4-8-2, 4-6-2, or 2-8-2 locomotive. After Dijon, the train left the main line to Marseilles and headed east through Aix-les-Bains, if there was a good moon, any of the party who could not sleep would have seen that the line has reached the foothills of the Alps, high mountains rising on either side. At Chambery a change-over to electric traction was made, from there towards Modane, the train passed through magnificent mountain scenery.

Modane is a single straggling Alpine township shut in, apparently on all sides, by high mountains. The “Rome Express” reached there roughly five hours and twenty minutes after leaving Dijon, At Modane most trains would undergo examination by Italian Customs officials and frontier police, The black-shirted military railway police (Milizia ferroviaria), were found on the trains, stations, and tracks all over Italy. The British received a more courteous reception. Initial impressions were good , they were warmly greeted (as indeed they were throughout the trip), At Modane conte Latour on behalf of the Italian Foreign Ministry welcomed them to Italy.

The train waited at Modane for half an hour, Italian clocks were on Central European time, so watches were put forward and the “Rome Express” now crossed the frontier behind an electric locomotive belonging to the Ferrovie dello Stato. The Italian electric locomotives worked on the three-phase system, double collector bows were mounted on the cab roofs, and there are two conductor wires overhead instead of one for each track.

After leaving Modane the line rounded a complete horse-shoe curve, rising all the way towards Mont Cenis at 6,860 feet, one of the oldest of the great Alpine tunnels, the whole of its length of 8 miles 832 yards bored without the aid of pneumatic rock-drills. At the Italian end of the tunnel the train passed through a gallery in the face of the mountain before finally emerging into the open. Looking back, was an unforgettable view of the snow-covered Alps, under which the train had passed, now towering into the sky

They arrived at Turin at 7.42 where they were greeted by more dignitaries- while the train was arranged with two carriages and a salon car being added to the Wagons Lits. After less than half an hour in Turin , they set off bound for Genoa. As far as Alessandria, the line ran through the fiat Northern Plain, past picturesque farm buildings of the traditional Italian type, with great white oxen ploughing in the fields and drawing carts along the country roads beside the line.

After Alessandria there was an end to the plain as the train turned southwards and began to climb into the Ligurian Apennines. At Ronco, 1,070 feet up and twenty-nine miles from Alessandria, they reached the watershed and the train soon ran down into Genoa past sunny south-facing hill-sides. The station at Genoa was a centre for international trains from many parts of the Continent. Coaches belonging to the Swiss Federal, German State, and Netherlands Railways are all seen in one train, bringing people down from Central Europe to the Riviera. At Genoa, the Italians put on another welcome. The man station piazza Principe was decorated with flowers, plants flags and bunting. A large reception committee consisted of Fascist officials from the Province of Genoa , Senators, Deputies and officials from the British Embassy and the local British community. A Fascist militia band provide a guard of honour, while Sir Noel Charles from the British Embassy in Rome presented the assembled dignitaries and then joined them for the rest of the trip. They were also joined by a Pathe cameraman. Chamberlain and Halifax dutifully inspected the guard of honour, chatted with the British community and after precisely 12 minutes they were off again. Chamberlain was seen waving off the crowds from the window of the departing train.

Leaving Genoa the electric locomotive proved itself to be a great aid to comfort, for the whole stretch down past Rapallo and Spezia was one long succession of tunnels through projecting cliffs. The intervening glimpses of Italian coast scenery, however, were charming from Rapallo to Spezia Luncheon and the incessant tunnels failed to distract attention from these lovely snatches of scenery.

After Rapallo the train headed down the beautiful coast of the Cinque Terre- mostly in tunnels

After calling at Nervi, Santa Margherita, Rapallo, and Spezia, the train turned inland at Viareggio to Pisa. At Pisa the famous Leaning Tower, Cathedral, and Baptistery were on the left side of the train as it enters the city. Continuing south they reached Livorno mid-afternoon., where the train changed back to steam traction. From Chambery, the all-electric stretch had been 334 miles long. The Italians had made railway electrification a matter of national policy, not least because of their shortages of domestic coal. Below Livorno. the coast was less impressive than the Italian Riviera, the journey continued with just a break to take on water at Grosseto. On the last stretch along the coast the “Rome Express” passed Tarquinia and then Civitavecchia, the ancient port of Rome before heading inland .

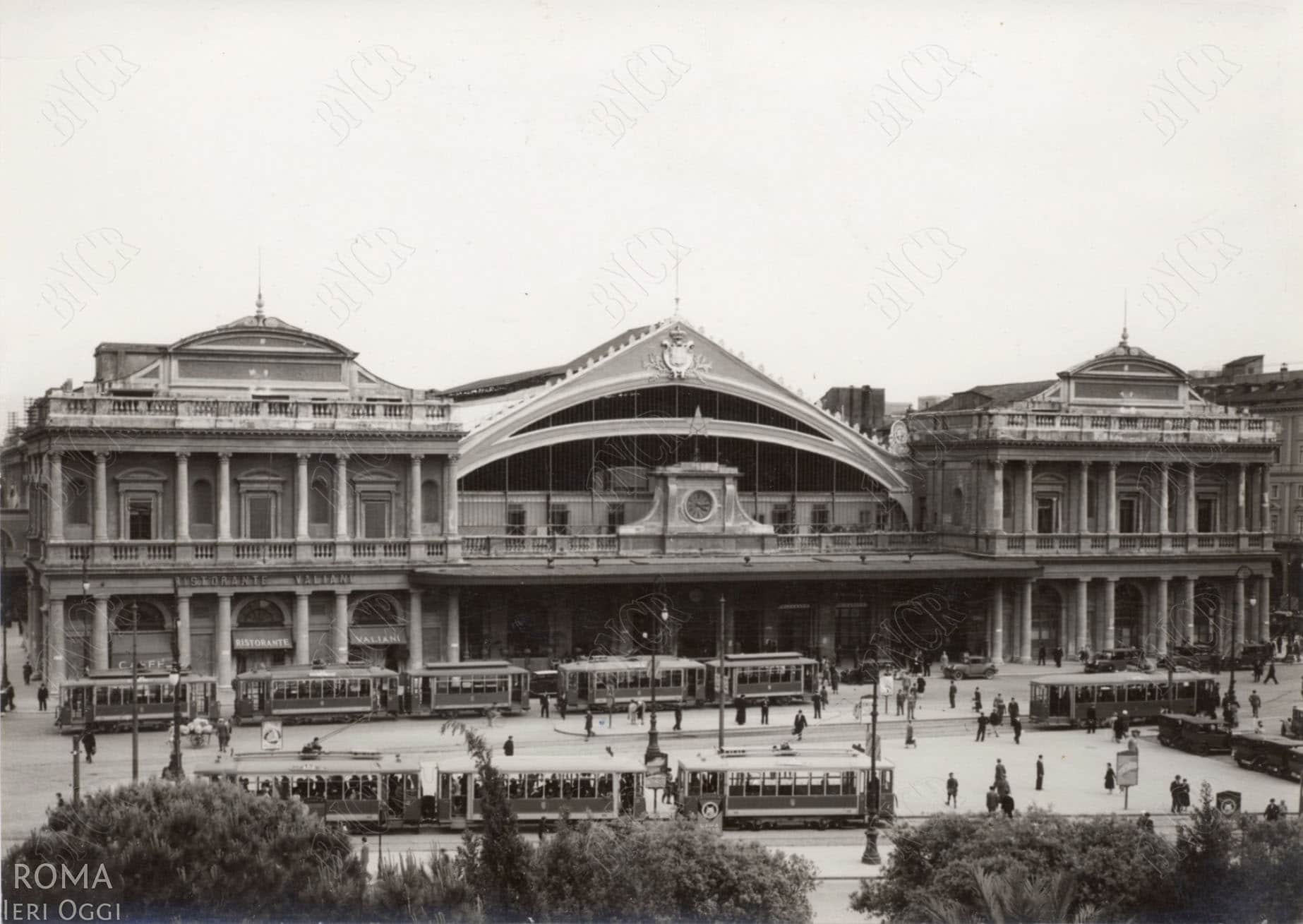

Roma Termini in the 1930s - before it was demolished and replaced with the modern station

The British party finally arrived in Rome at around 4.30 in the afternoon. They were treated to usual display of plants and flowers. Two platforms had been boarded over and carpeted to allow a sufficient space for all the greetings. The old Roma Termini station was still working, but the surrounding area was in the process of demolition, ready for a brand-new modernist station to open in time for the Universal Exposition (EUR) planned for Rome in 1942. Fortunately , the Pathe Cameraman on the train was able to film the waiting Italian delegation as the trained arrived. Chamberlain stepped off the train, looking remarkably unruffled after his 18-hour trip, dressed in his habitual morning dress, with striped trousers and tails , impeccably starched stiff collar and trademark umbrella. Mussolini was in military style black greatcoat and cap, while Ciano had gone for a lighter grey version of a similar ensemble. Some of the crowd cried out “Ombrella” as Chamberlain passed.

Chamberlain and Mussolini inspect the guard of honour at Roma Termini

The greetings wee affable enough, one could not say they were old friends, but Chamberlain had met Mussolini four months before at the Munich Conference . Mussolini had also met several times with Chamberlain’s half-brother Austen and his wife both of whom he had been on good terms with. They had held several off the record personal meetings in the 1920s. Chamberlain had also been using his sister-in-law Isabel as an unofficial conduit to Mussolini. one of the reasons that Anthony Eden got annoyed and resigned Ciano was known to most of the diplomats already. Neither Ciano or Mussolini were convinced regarding the usefulness of the visit.

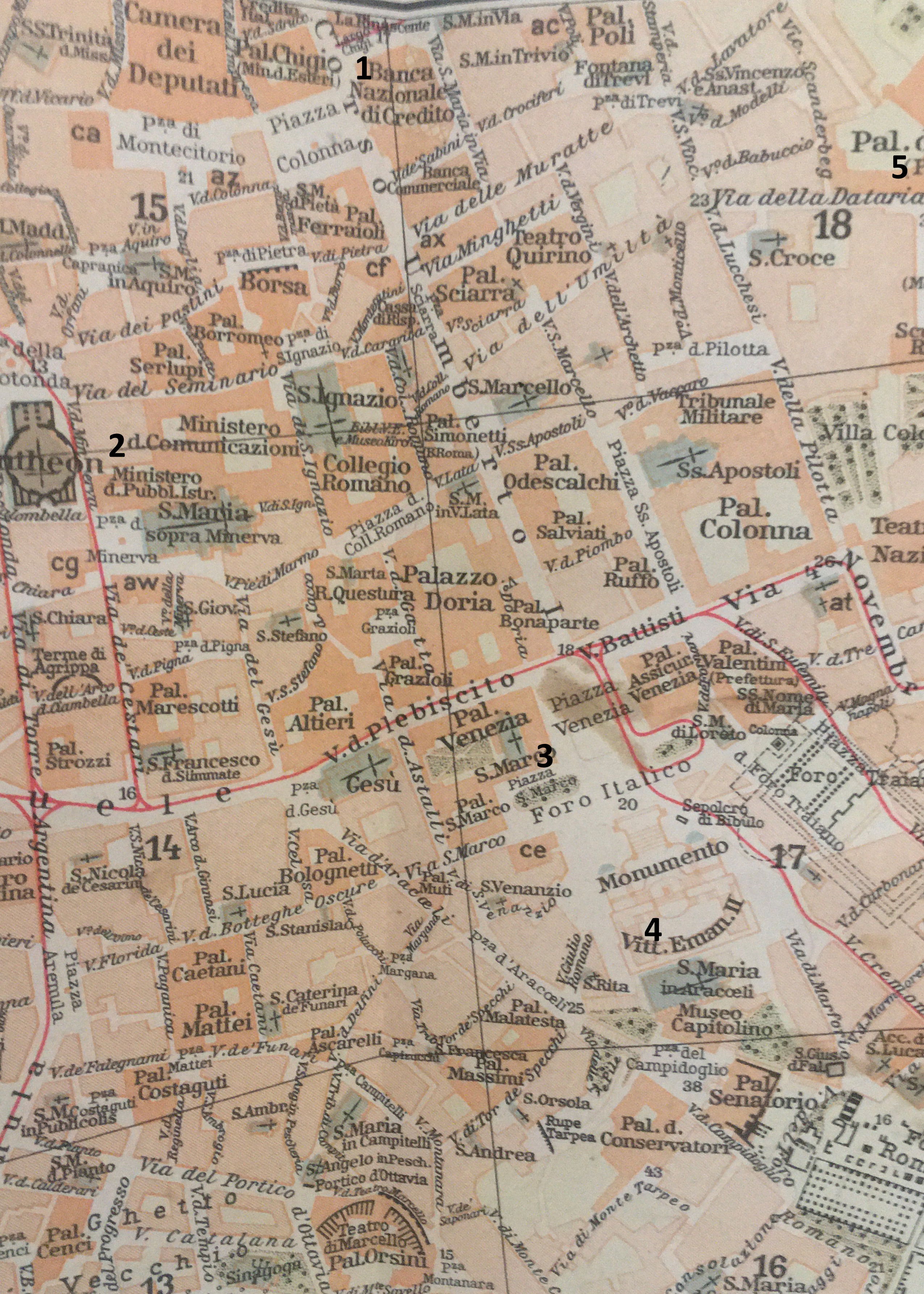

From Roma Termini the British were whisked way in a fleet of Lancia limousines to the Villa Madama, Chamberlain was accompanied by Ciano in an open topped Lancia. On arrival Ciano proudly gave the British guests a very quick tour of the villa and its splendid views. There was a short time for some tea and to freshen up. before being driven back to the centre of Rome for a 5.45pm meeting with Mussolini at the Palazzo Venezia.

The main entrance to the Palazzo Venezia where the British Party arrived

The other diplomats stayed outside while Chamberlain and Halifax were ushered into the Sala Mappamundo. The room was built by Pietro Barbo, immediately after his election to the papacy under the name Paul II (1464-1471) as a reception room: The room was named due to a long lost planisphere formerly located in the centre of the western wall, now lost. The room had been used by the popes to welcome guests until the end of the sixteenth century, in this historic room Pope Paul III met Charles V and established the convocation of the Council of Trent. The room had latterly been used as the location of newly established Museum of the Palazzo Venezia in the first decade of the twentieth century but was then chosen by Mussolini as his own headquarters: he placed his desk next to the fireplace, worked in this room, received guests and harangued the crowd from the balcony just outside.

Decorated in the second half of the fifteenth century, the room underwent numerous changes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In 1917, the art historian, Federico Hermanin, then Superintendent of the Galleries and Museums of Lazio and Abruzzi, restored the fifteenth-century layout and rearranged the space to look like a Renaissance residence. The walls featured fake architectural details creating the illusion of an even larger space. These details include a portico with eight columns on bases in the form of a classical temple and a frieze decorated with medallions with the Doctors of the Church. This decoration was subsequently covered with a layer of plaster and painted over with other images. Hermanin salvaged the few surviving fragments, attributed them to Andrea Mantegna and entrusted their restoration and reintegration to the painter-restorer Giovanni Costantini. The ceiling, the chandelier and the mosaic floor were added during the 1920s by Frederick Hermanin based on a model from 1496 in the church of San Vittore in Vallerano, near Viterbo. The floor, the work of Pietro D’Achiardi (1879-1940), depicting The Rape of Europa with marine gods and zodiac signs along the border; it was inspired by the mosaics in the Baths of Neptune in Ostia Antica. Fairly appropriate considering what was going to happen.

The floor in the Sala Mappamundo- aptly depicting the "Rape of Europa"

Mussolini’s desk was by the monumental fireplace at the far end of the hall. the fireplace bore the cardinalate coat of arms of Marco Barbo and was embellished with a frieze containing ribbons, leaves and fruit, the fireplace has been attributed to Mino da Fiesole (1429-1484) and Giovanni Dalmata (1440-1515).

Mussolini's desk in the Sala Mappamundo

A view of the Sala Mappamundo. Post- Mussolini-the window archives where Mussolini entertained his lady friends are still tyhere.

Some details of the floor of the Sala Mappamundi

Presumably as he made the long walk towards Mussolini’s desk, Chamberlain was unaware that the cushions in the window alcoves were allegedly used by Mussolini to entertain his harem of visiting female companions. Flanked by Ciano and referring to a set of handwritten notes, Mussolini faced Chamberlain and Halifax across the desk. There they were, a former Lord Mayor of Birmingham, former Viceroy of India and a former teacher, journalist, soldier, and oddjobber, together with a man qualified for his post by being his son-in-law. Galeazzo Ciano was the son of Admiral Costanzo Ciano a founding member of the Partita Nazionale Fascista (PNF). Both were Fascist early adopters and had taken part in the March on Rome in 1922. The family had profited well from their early connections with fascism, owning a newspaper and a property empire in Tuscany- Galeazzo was already used to a high-profile and glamorous lifestyle, when having dabbled in journalism he embarked on a career in the Italian Foreign Service. His fortunes took an even better turn when he in 1930 he married Mussolini’s daughter Edda. Th couple went off to China, where Galeazzo became Italian consul in Shanghai. On their return to Italy in 1936, his father-in -law appointed him minister of Press and Propaganda Mussolini spoke French fluently but had limited English (presumably just enough to say thanks for the bribes the British paid him during the First World War) , so he asked to speak in Italian with Ciano translating.

Responding Chamberlain turned on the charm

“To begin with, he wished on behalf of himself and the Foreign Secretary to thank Signor Mussolini very warmly for his invitation, which it had given them great pleasure to accept. He had felt that, when he parted with Signor Mussolini at Munich, he had not seen enough of him, and was extremely glad to have an opportunity of renewing the acquaintance which was then begun. “

In his diary Ciano described the conversation s being in a “tired tone”, with the matters discussed not highly important According to Ciano, Mussolini was not impressed by his British guests.

“These men are not made of the same stuff as the Francis Drakes and the other magnificent adventurers who created the empire. These after all, are the tired sons of a long line of rich men and they will lose their empire”.

The next day started with a visit to the Pantheon at 10 am, Chamberlain and Halifax visited briefly and laid wreaths to Umberto I, the current King’s father who had been assassinated by an anarchist in Monza in 1901, while watching a gymnastics display. This was followed by a more symbolic visit to the tomb of the Milite Ignoto known soldier at the altare di patria to pay their respects. On 28 October 1921, Maria Bergamas the mother of an Italian soldier lost in with no known grave had selected a body from eleven unknown Italian casualties laid out in the Basilica of Aquileia. The body had been taken to Rome where over a million people attended its interment. Symbolically, part of the crypt was made from marble from the carsto and from Monte Grappa where thousands of Italians had lost their lives.

Chamberlain, Halifax and the British Ambassador, Lord Perth climbed the steps the memorial surrounded by a large of uniformed Italians, some of whom might have fought alongside the British and French in the First World War. The scion of a Scottish noble family, the Eton educated Sir Eric Drummond had joined the British Foreign Office as a clerk in 1900 and worked his way p becoming Private secretary to two Foreign Secretaries, Sir Edward Grey and Arthur Balfour and to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. He had been a member of the British delegation to the Paris Peace Conference and had then put forward by the British as the first Secretary general of the League of Nations, where he was instrumental in building up the Secretariat. His period at the League of Nations had already coincided with several Italian related problems – not least the 1923 Corfu incident. Since becoming Ambassador to Italy in 1935, the problems on his plate had multiplied with the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, sanctions, the Italian intervention in Spain and their deteriorating relations with the French. In 1937. Drummond had acceded to the title Lord Perth. On 28 September 1938, Lord Perth had sought an urgent audience with Ciano requesting Mussolini’s intercession in the Munich crisis. Mussolini prevailed on Hitler to delay his advance into the Sudetenland, a four-power conference was convened and Chamberlain few to Munich. He told the House of Commons

“Whatever opinions you, my honorable colleagues, may have had the past about Mussolini, I think each one of you will recognize in this action a desire to contribute with us to peace in Europe!”

They were followed by the Military attaché from the British Embassy, Colonel Monague Brocas Burrows, the Naval Attaché Captain Robert H Bevan and the Air Attaché Group Captain C. B. H. Medhurst.

Itinerary in Rome 1) Palazzo Chigi - Halifax and Ciano meeting 2) The Pantheon - wreath laying for the late King 3) Palazzo Venezia meetings with Mussolini 4) The tomb of the Milito Ignoto- more wreath laying 5) Quirinale - lunch with the King

During the morning Halifax also held talks with Ciano at the Palazzo Chigi, where they discussed Spain. Although the British might have suspected it would happen; Ciano was quick to feed back the substance of the talks to Von Ribbentrop- he described them as a” lemonade” absolutely harmless.

Chamberlain went to the Palazzo Quirinale for an audience with King- Emperor Vittorio Emanuele III and an official lunch. ( There is no record on their discussions with the King)., the Crown Prince and other Royal Family Members were also present. Unlike Mussolini the King spoke fluent English. He had also met two previous British Prime Ministers, Herbert Asquith, and David Lloyd George during Italy’s First World War alliance with Britain. Chamberlain apparently hated Lloyd George, so hopefully the King styed quiet on that topic, He had also met the late King George V and in 1916 and 1918, the young Prince of Wales, now in exile as the Duke of Windsor. Since Chamberlain had been prominent in urging for King Edward VIII’s abdication., that topic might have been off limits. If all else failed they might have discussed the king’s interests in numismatics, The king was notoriously short in statute, so presumably they kept him from standing too near to the towering figure of Lord Halifax.

Royal visit done at 1500, the British had the dubious pleasure of a sporting/ gymnastic/ choral display by the Fascist youth group, the GIL. Watching from an observation platform in the company of Ciano and Mussolini the British guests were treated to Italian youth singing God Save the King in English followed by a rousing chorus of the Fascist hymn Giovenezza. There followed an interesting display of young women showing off their skills with medicine balls and closing with an artillery barrage. “The Sports Exhibition had also been extremely impressive; both as regards the speed of movement and the accuracy of the co-operation and precision attained not only by adults but also by little boys of six to eight. There had been some criticism among the Italians of allowing small boys to carry rifles and to drill with arms. It was evident that this form of exhibition was more agreeable to Signor Mussolini than attendance at social functions.” Oliver Harvey described the scene

“The display was by youths and girls of 14-18 and a few small boys of eight upwards. The drill was very good, but we all found the passo romano quite ridiculous. It was all very militaristic and the sight of the little boys with their miniature rifles was quite revolting”

Harvey was sat near to Dino Grandi, the Italian ambassador to the Court of St James, who explained to him that the real purposes of the GIL and all the training was to counter the influence o the Pope. Grandi was another who had been involved in Chamberlain’s behind the scenes discussions with Italy.

Chamberlain and Halifax had further talks with Mussolini and Ciano at the Palazzo Venezia at 1730 covering a number of topics. Then they had a well-deserved break for a night at the Opera At 21.00 at Teatro dell ‘Opera di Roma, they were treated to highlights from the ballets Rossini’s Boutique Fantasque and extracts from Verdi’s Falstaff. The artistic director was renowned conductor Tullio Serafanin. The orchestra played God Save the King , the Royal Anthem and Giovenezza. The British may have been unaware, that even more renowned Italian conductor, Arturo Toscanini had fallen out with Mussolini and gone into exile rather than play Giovenezza at La Scala in Milan. Anyway, it seems unlikely that the British in their courting of Mussolini, would want to mention the ugly topic of political dissent or the large number of Italians languishing in goal or in internal exile for opposing the Mussolini regime. While Serafinin was later to take his production of Falstaff on tour to the Opera House in Berlin. Toscanini remained in exile in New York. Both Boutique Fantasque and Falstaff were on the repertoire of the Opera. Presumably the Italians thought that Falstaff would appeal to the British and Boutique Fantastique was on anyway ! . Neither were likely to be politically controversial. For an audience of some 2,000 , Mussolini and Ciano had opted for normal white tie and tails, so the British guests blended in, except Lord Halifax seemed to have more decorations than anybody else. Assuming they were still awake, it was then off to the prestigious ( and fortunately nearby) Hotel Excelsior in the via Veneto for a late dinner hosted by Ciano. Apparently, it finished around 3am. Nobody record what time Chamberlain got to bed, or what the distinguished British guests thought of eating so late. For a 68 -year-old, Chamberlain seemed to have coped quite well.

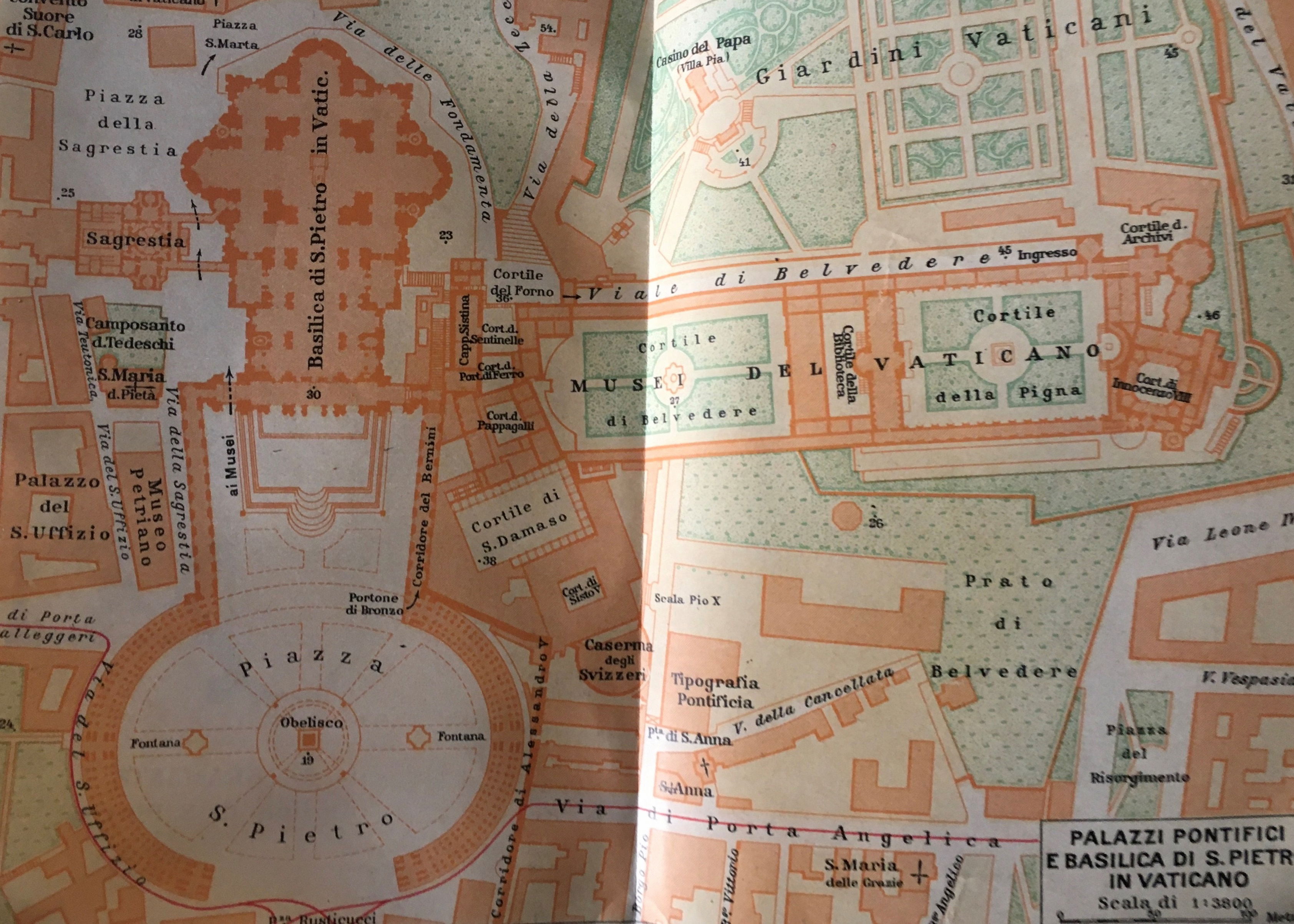

The following morning, they were taken back to the British Embassy where Halifax updated the American and French Ambassadors on their talks so far and then to the British Legation to the Vatican, where they met the British envoy to the Vatican D’Arcy Osbourne. Osbourne was another with Italian experience. Educated at Haileybury College, he had previously served at the British Embassy in Rome on two occasions (1909 to 1913 and 1929-31) before being posted to Washington. In 1936 he was appointed envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Holy See. They might have need surprised to be picked up by a fleet of Papal Buick limousines, the Pope was a fan of America cars.

82-year-old Pope Pius XI was a dying man. Pope since February 1922, following the signing of the Lateran Treaty in 1929 he became the first sovereign of an independent Vatican City. On 25 November 1938 he had suffered two heart attacks in a few hours thereafter he suffered from severe bronchial problems and was effectively confined to his Vatican apartments. Relations between the British and the Papacy had been strained over the previous years, having been downgraded in the early 1930s over a row regarding Papal interference in Malta. Apert from being a courtesy visit, the British seemed keen to repair relations with the Vatican. The British must have been surprised when a fleet of Buick limousines bearing the Papal flag arrived to pick them up. Pope Pius XI liked American cars. Chamberlain was joined in the first car by Sir Martin Mervin, a British Papal camerlengo ). Mervin was a catholic businessman from Birmingham who owned the Catholic newspaper “The Universe”. Two "chamberlains "from Birmingham in an American Limousine, heading to meet the Pope.

A Tour of the Vatican

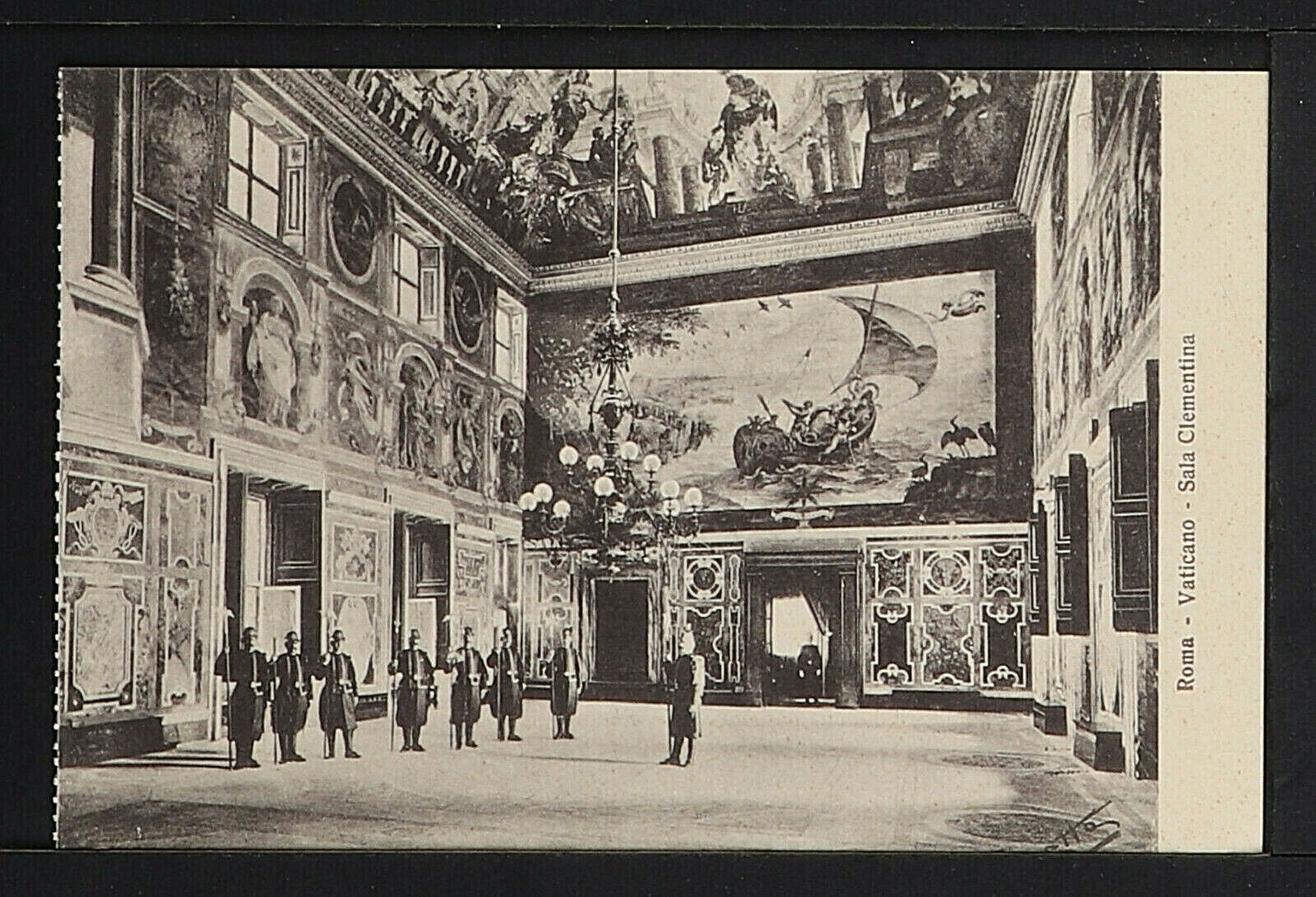

The motorcade took the British guests into the San Damaso Courtyard where they were ushered into the papal apartments. They were greeted by more Papal Chamberlain and shown up to the Sala Clementina where British, Canadian students at the Vatican Colleges lined up to welcome them. The room was dominated by the fresco “The Martyrdom of St Clement” by Dutch master Paul Bril, the “Baptism of St Clement” by Cherubino Alberto and Baldassare Croce,, looking up at the ceiling by “The Apotheosis of St Clement” by Giovanni Alberti.

The Sala Clementina at the Vatican

The procession was received by Monsignor Arborio-Mella, the Pope's Master of the Chambers. Chamberlain, Halifax, and Osborne were ushered into the Pope's study. His Holiness was awaiting them standing, and, after shaking hands, invited them to sit down. The party was then joined by Monsignor Hurley, an American ecclesiastic in the Secretariat of State, who translated. Hurley from Cleveland, Ohio had embarked on his vocation as a priest and travelled with apostolic delegation to India and Japan, before becoming the first American to serve in the Vatican Secretariat. Osbourne was supposed to translate for the British, but it became clear that the Pope understood English. In reply, the Prime Minister said that he, and indeed all England, deplored the sufferings inflicted upon Catholics, Protestants and Jews in Germany; he and His Majesty's Government would be naturally most ready to intervene or intercede, either in Berlin or in Rome, in any way possible that offered a hope of improving the situation; but, for the moment, he saw no such hope, indeed, more evil than good might be done in present circumstances by an untimely and impolitic intervention; His Holiness could, however, rest assured that he had the matter in mind and, should an opportunity occur, would do his best. Thereafter, Lord Halifax reiterated the Prime Ministers expressions of gratification at His Holiness's reception and added that his visit to the Vatican impressed him the more deeply in that it was 43 years since he had accompanied his father to an audience with Pope Leo XIII.

Finally, the Pope asked Mr. Chamberlain and Lord Halifax to accept, as a memento of their visit, a gold medallion representing the recently canonised English martyrs and saints, Thomas More and John Fisher; this was, he pointed out, apart from other interest, a very respectable work of art; the representation of himself on the reverse would, however, he added, appear to those who saw him to-day altogether too flattering. Due thanks were returned for this gift, together with final assurances of goodwill. The four other members of the party were then introduced, and the Pope rose and shook hands with them. is Holiness then walked briskly across to a shelf where was a silver and enamel diptych, presented to him by the English College in Rome, representing Saints Thomas More and John Fisher.

" You may tell their Majesties, you may say it to all England, " he said, " that England is always with me." Harvey described the meeting the Pope. “

The Pope , who was dressed in white , was sitting on a sort of throne at the top of a table at which the PM, H and D’Arcy Osbourne wee sting. He rose as we came in and came towards us, a most impressive figure , very small, very frail and fragile-looking, skin transparent like parchment as if he were only alive by willpower.” Harvey describes how the British party, somewhat overwhelmed temporarily forgot the protocol for visiting protestants and dopped t their knees to take the Pope’s hand The party, which was then formally conducted, down the Grand Stairway, to the Apartments of the Cardinal Secretary of State the Prime Minister, the Secretary of State and Mr. Osborne were invited into the cardinal's study and a short conversation took place, after which the party were presented to Cardinal Pacelli. Leave was then taken of the Vatican officials and the return journey was made, in the same Vatican cars and in the same order, to the British Legation.

Luncheon was attended by Cardinal Pacelli, who thus fulfilled the formality of the return visit, Cardinal Pizzardo, who had been the Pope's Legate to the Coronation, Monsignor Mella, the head of the Papal Household, Marquess Serafini, the Governor of Vatican City and various other British and Papal dignitaries were present. Pius XI died shortly after the meeting, in February 1939 and was succeeded by Cardinal Pacelli as Pius XII.

The afternoon was set aside for an exciting tour of the Mosta Autiarcha del Minerale Italiana. The exhibition was arranged in Pavilions in the Circus Maximus. The intention was to show Italy’s self-sufficiency in minerals and the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations Sanctions which had been imposed following the invasion of Abyssinia. The modern pavilions designed by contemporary Italian artists were devoted to Lignite, Pyrites, Graphite. Lead and Zinc, the Progress of Italian Arms, and the Defence of the Race. Strangely thee ere no pavilions devoted to coal or oil. Visiting dopolavoristi (after work parties) had been touring the site for the previous few months, inspecting the displays of minerals, the latest weapons and being impressed by the giant eagles and the motto “Mussolini is always right”. Maybe Chamberlain, who had studied metallurgy and science would have been one of the few to find anything of interest in the display.

A Pathe newsreel cameraman was on hand to record highlights of the tour. The British party are all in their habitual Morning coats and striped trousers and top hats as they walk round. They are surrounded by men uniforms, some of them appear to the Carabinieri guarding them, the rest appear too be various Fascist officials. Throughout Chamberlain doffs his top hat and tries to look interested.

Reporting back to the Cabinet on the exhibition , he said that the Exhibition

“was a piece of clever propaganda for the Fascist Party. A geological survey of the country had been, carried out within the last few years, with the result that many valuable minerals had been discovered, including coal and anthracite. These were now being exploited. The Exhibition gave full details to show the increasing output of the minerals and the methods of exploitation. The Prime Minister had felt some doubt, however, whether all the development illustrated paid its way.”

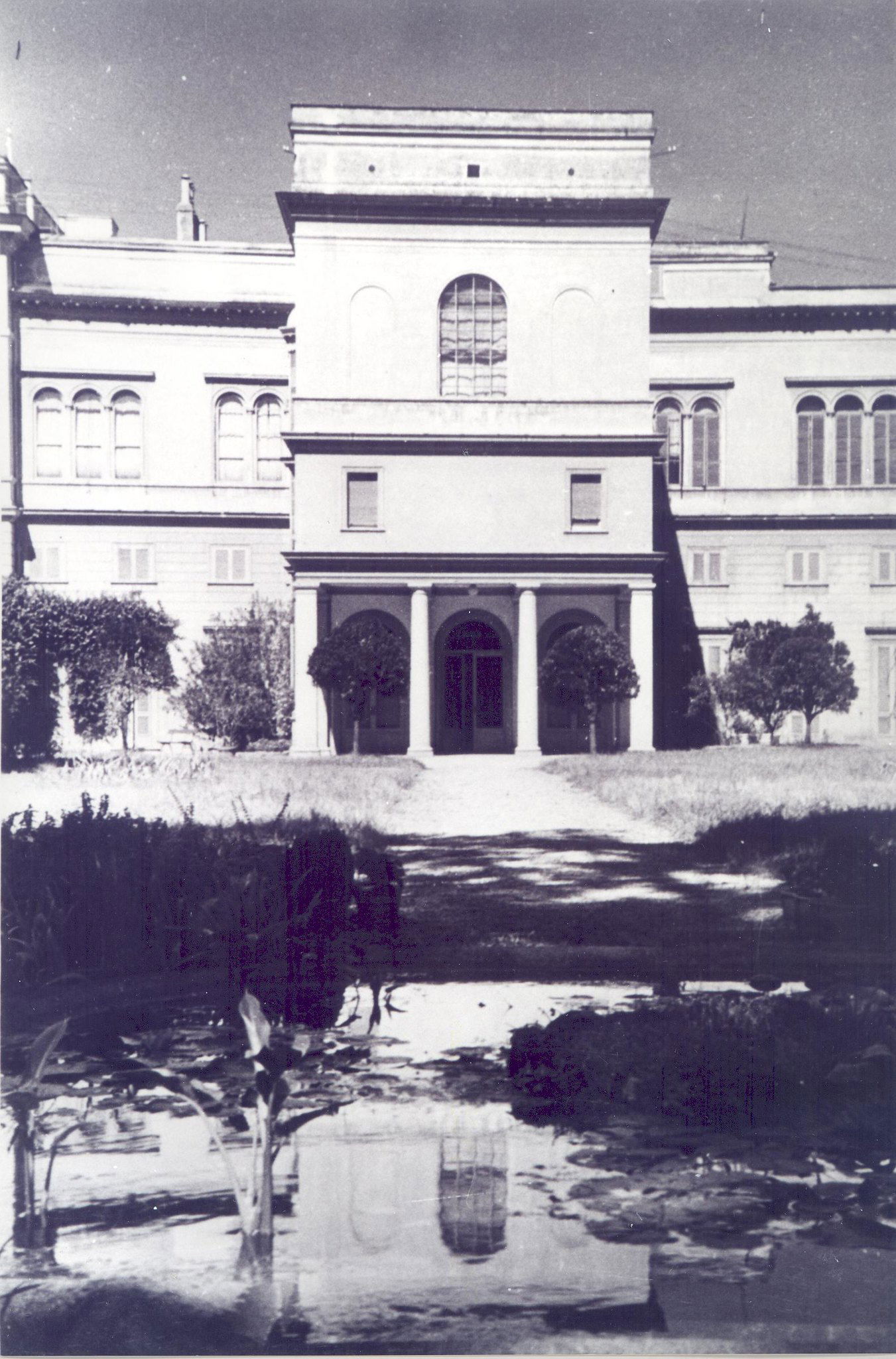

The visit was followed by a reception and concert at the Capitoline hosted by the Governor of Rome and a reception at the British Embassy attended by both Mussolini and Ciano. The British Embassy was by the Porta Pia in an old palace, with extensive gardens bordering on the walls of ancient Rome. The Embassy is still there, albeit in a different building. The original was blown up by Zionist terrorists in 1946, shortly after Sir Noel Charles, the former counsellor who had been sent to meet Chamberlain and Halifax at Turin, had returned to Rome as Ambassador. Fortunately he was out at the time and escaped harm.

The Old British Embassy in Rome- it was blown up by Zionist terrorists in 1946

Chamberlain left Rome the next morning, with a formal farewell from Mussolini at Termini station. Ciano describes the leave taking as being brief but cordial, with Chamberlain’s eyes filling with tears as the local British community sang “For he’s a jolly good fellow”. Mussolini was apparently not familiar with the song.

When the British reached Turin at 21.00, there was another formal farewell committee with the Prefect, local dignitaries, the British Consul, and the local British Community. After ten minutes of farewells, Chamberlain headed home, while the assembled British gave a stirring rendition of God Save the King. Parties of Italians turned up at all the stations on the way to the frontier at Bardonecchia to salute the departing British Prime Minister.

Nothing concrete had been gained by the visit. As the British left hostility between France and Italy was ramping up again over Corsica, the Nationalist rebels were advancing in Catalonia and the Italians were worried that the French were on the verge of intervening. Shortly afterwards, the Italians invaded Albania. Even if relations between Britain and Italy remained cordial, Italian hostility to France was out in the open. Eighteen months later many of the British community would have to flee the country or faced internment, with their assets sequestrated by the Italians.

Chamberlain sent Mussolini a telegram on leaving Italy on the night of January 14.

“Sua Eccellenza Benito Mussolini, Roma, I CANNOT leave Italy without expressing to your Excellency my warm thanks to you personally and my deep appreciation of the welcome accorded to me not only in Rome, but throughout the course of my journey on Italian soil. These sentiments are fully shared by -Lord Halifax, and we both return to England fortified in our belief in Anglo-Italian friendship and in our hopes for the maintenance of peace."

NEVILLE CHAMBERLAIN, January 14, 1939.

Halifax meanwhile had taken the train with Harvey to Milan, the had an hour of sightseeing at the Duomo between trains before heading to Geneva. On their journey, Harvey and Halifax were able to discuss their impressions of the Italian trip. They believed that the Italian people were on their side – having turned out spontaneously to greet the British visitors rather than being forced out as they had been for Hitler. Even Mussolini had remarked on Chamberlain’s popularity. They had found Mussolini to be calm, unaggressive and rather different from how they imagined. Ciano they appraised as “obviously a lightweight enjoying the sweet life to the full” Edda Mussolini Ciano they saw as neurotic and obsessed with her health. “

They even gossiped about Mussolini’s mistresses.

“-He had an Italian woman who was supposed to be exhausting him and now has a German or Czech one who is said to be much easier”

The British were well informed. Mussolini was indeed taking a break and trying to downscale his relationship with Claretta Petacci at the end of 1938, saying she was no longer welcome in his private site the Sala di Zodiaco at the Palazzo Venezia and banning her from public functions. However, their relationship rekindled, and they were together right up to the Standard Oil Filling Station in the piazzale Loreto) As their train crossed the Swiss border at Domodossola, Harvey’s reflection was that

“Mussolini has done immense things for the country, public works, stiffening the morale , youth movements, increasing self-confidence and national pride. But the country remains what it always has been a lightweight outfit, no raw materials, no real stamina to face a modern war. Mussolini will use every opportunity to blackmail us, the French and Germans but not to fight”

Maybe Chamberlain’s policy was not o misguided. The Italians initially stayed out of war and continued to trade and talk to the British right up to May 1940. British engagement with Italy, may have prevented some earlier French - Italian conflict and bought everybody just a bit more extra time. In the end Mussolini couldn’t resist attacking an already beaten France to miss out on the long desired Nice, Savoy, Corsica, and bits of French North Africa. Having decided to invade an already beaten France, he had little option but to simultaneously declare war on the United Kingdom. Possibly Anthony Eden had been right about the dangers of dealing with “gangsters” all along.