On the trail of Edward Brittain- Along the Piave and on Montello- January 2020.

Having taken a pause from my Brittain/ Lister book project since the trip to Asiago for important things like working for a living, I had a couple of days free to pick things up again. So I headed east from Milan towards the River Piave.

The River Piave looking north from Nervesa

The River Piave looking north from Nervesa

In October 1917, the Italian Army collapsed at the Battle of Caporetto and retreated westwards with the Austrians and their German allies in hot pursuit. The Italians lost a huge amount if territory in Veneto and Friuli, retreating as far as the Piave where they established a new defensive line on the Western bank. If that line broke and the Austrian and German forces crossed the Piave, then the rich and virtually indefensible Italian plain lay wide open to then including the valuable cites of Padova, Vicenza and Verona- not to mention an Austrian reoccupation of Venice ( from where they had been ejected in 1866. An Inter-Allied Conference in Rapallo, the British and French offered to send five divisions to Italy to prop up the Italian front and towards the end of November 1917, the first units of the British 4th Army began to take over positions along the Piave from defending Italian units. The British units deployed along the Piave included the 11th Battalion Sherwood Foresters and Captain Edward Brittain M.C.

The British Divisions were initially deployed along the banks of the Piave from Crocetta Trevignana ( now Crocetta Montello) down towards Nervesa ( now Nervesa della Battaglia) . Above, the river stretches a long whale shipped hill, called the Montello. The British frontline trenches were along the riverbanks, with their second line and reserve trenches up on the hill. The best centre for a tour of the area seems to be Nervesa, which gives access both to the banks of the Piave and up onto the hill of Montello. Therefore, I have booked a B&B in Nervesa from which to explore the area.

I set off around 8am. I manage to find an excellent local map, in a newsagent- as well as some local guidebooks. A real paper map proves a much better alternative than trying to navigate the Area using an IPhone, with fading battery and intermittent GPS. Armed with map, I follow the road out of the town to the north. Here there is a choice between the high road or the low road, the high road is the strada panoramica, which goes up a series of hairpins onto Montello, the low road runs along the river bank-at least for the first part. I take the low road.

To begin with, the low road is in good condition– the strada coderi, which runs across the floodplain. This is road was used by quarrymen who cut the rocks from the escarpment of the Montello and shipped them downriver by raft. At this point, the Piave is wide with wide meadows along the floodplain. A few kilometres out of town along that route, there is small grass airfield, which houses a collection of vintage aircraft, The Jonathan Collection. It is still early in the morning and it has not opened yet. I continue on my way with meadows and the river on one side and vineyards on the other. Finally, the route is blocked by a small hydroelectric facility, so I have to retrace the path back through the meadows and stay a bit farther from the riverbank.

The riverbank path is scenic, but challenging. In parts, the path seems to have been reclaimed by the river, leaving little alternative but to walk along narrow stretches, at some risk of putting a boot in the river. Not that Piave is actually very deep at this time of the year- although as I found it is certainly deep enough to fill up a boot with water. After a while, the river widens, with a thin strip of woodland running along the riverside, while some fairly steep cliffs rise up to the Montello. The river changes nature, it becomes wider and in parts, reduces to small channels between wide islands of shingle. After the Italians had crossed the Piave, they had hastily dug a front line of trenches along the riverbank and the British had improved these and created the second and reserve lines. Down by the river, there is no longer anything at all, you could identify as being a trench. I suppose that the river had washed them away. There are a number of Italian defensive constructions to see; every so often, you see a sign “Al Bunker”. Local history groups have restored them. After the British left the Piave for the Asiago sector, the Italians perfected their bunker building skills down here. Every natural looking rock formation seems to have some ingenious machine gun nest or observation point blasted into them.

The Italian Art of Digging Bunkers

The Italian Art of Digging Bunkers

You can go in and stare out across the river to where the Austrian positions would have been on the other bank. Writing to Vera Brittain from the Montello on 4th December 1917, Edward Brittain says of the frontline on the Piave:

“We are in the front line- a most extraordinary place- very quiet at present and very few shells… The Piave is very wide just here and so the Germans and the Austrians are a long way off. One pf our chief difficulties is getting enough to eat and smoke….”[i]

Changing faces of the River Piave

Changing faces of the River Piave

After around a kilometre or so of scrambling up and down to bunkers, the riverside path virtually disappears. There is a last highly dubious bit, where in order to get along, I have to shimmy along sideways, while clinging to tree roots and hoping that the rather unstable looking river bank does not collapse on top of me. This route is definitely not recommended for the unsteady of foot.

Somewhere around Croda Rossa, I abandon the riverbank and head up for the strada panoramica again, looking down over the floodplain. By this time, it is around 12, 30 and I am seriously in need of something to eat and drink. I finally reach a welcoming Osteria, called the Cippo degli Arditi. Here I have a large mixed grill of local pork with Polenta, washed down with a pleasant ¼ litre of local red wine. Edward Brittain has a little dig at both the Polenta and local wine in one of his letters, but this was not at all bad

Montello Pork and Polenta

Montello Pork and Polenta

At this point, it would have made sense to head back towards Nevesa, instead I am tempted to get away from the river bank and up to the top of the Montello to see how things look from there. On the map, I have noticed that the Osservatorio del Re, does not look far away, so I head for there. It turns out to be quite a challenging hike up to the Observatory, which is really just a farmhouse where the King used to go up and look out over the Austrian lines from the upper storey.

The view from the Osservatorio de Re

The view from the Osservatorio de Re

It has taken a while to get up to the Osservatorio and I am now left with a bit of problem , I have a choice of 11km back along the dorsal road of the Montello back to Nevesa , or a 7km descent to Montebelluna. I work out, that if I do the 7km, I might just hit a street lit area by the time it gets dark and then find a bus or taxi in Montebelluna to get back again, I calculate the Nevesa route will leave me up on the plateau in the dark, with only a small iPhone torch for light. I start off on the descent toward Montebelluna. Up on the plateau, one of the stranger features of the Montello becomes more apparent, the whole surface is cratered with deep pits, called dolina. The word is of Slovene origin describing a closed cone shape, formed from water infiltrating the calcerous rocks of the plateau. These Dolina range from small holes, to deep steep sided craters. One of the advantages they presented to the British forces occupying Montello . was a place to hide artillery pieces- although given the limited elevation of some of the guns and the deepness of some of the dolina, getting the right firing trajectory was to prove a challenge.

I finally get off Montello at Pedervia, this one of the 11th Battalion’s rest areas, when they were out of the line. It is a very small place; most of the houses look very modern, I am assume there was not much there in 1917. At least Pedervia sort of feels back to civilisation, with pavements and streetlights. I walk through there to Biadene; the Sherwood Foresters held a shooting competition here in early 1918. I walk into Montebelluna on the main road. Now it is built up all the way into Montebelluna, with furniture stores, DIY superstores and car showrooms there is nothing there. The main benefit seems to have been that they are both on the rear side of the Montello away from the river and presumably provided a welcome respite from Austrian and German shelling across the river-

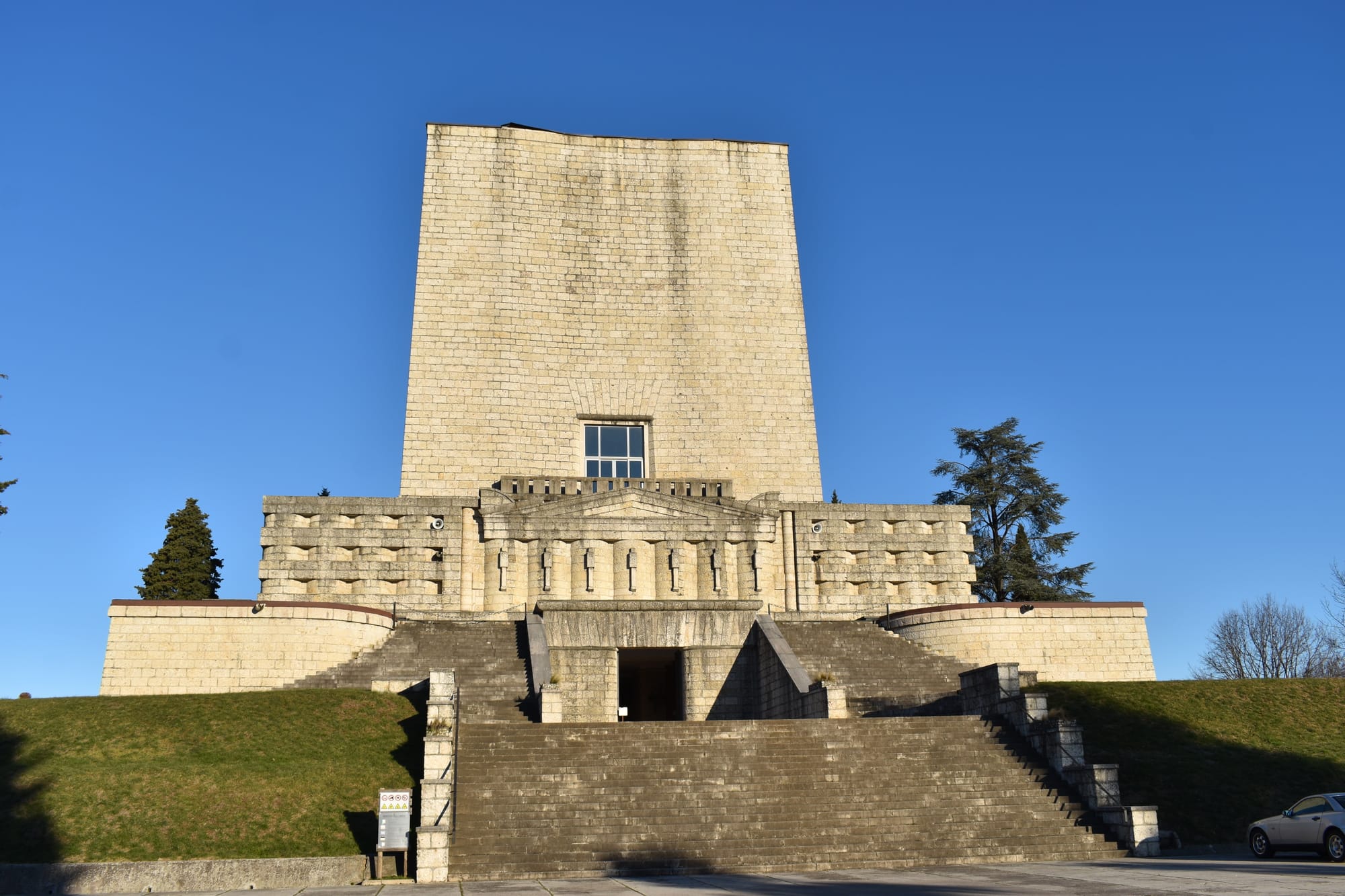

The next morning, I set out early to do the road, which runs behind the Montello with the intention of getting at least as far as the British Cemetery at Giavera. My first stop on the way is at the Italian Sacrario, the Ossario del Montello. The Ossario contains the remains of 9,325 Italian soldiers who died in the various battles along the Piave between November 1917 and October 1918. Only 6,099 of these are identified. It was a policy under Mussolini’s Fascist Regime to disinter in the Italian War dead from the cemeteries along the battlefront and to concentrate them in 40 large memorials, which served the purpose of creating a mythology of the war dead, rather than remembering the individual soldiers. The Ossario was finished in 1935 and from its position at 160 m above sea level, it dominates the town of Nervesa. Illuminated at night it can be seen from most parts of the town. Inside the monument are panels with the names of all the 6,009 known dead and commemorations for the unknown. From terraces higher up in the building, you can get a panoramic view of all aspects of the Battle of the Montello and down across the Venetian plain towards Treviso and the Venetian Lagoon.

Ossario di Nervesa della Battaglia

Ossario di Nervesa della Battaglia

Back down the hill from the Ossario, the road runs through vineyards and small farming communities along the base of the Montello. Most of the houses are new and prosperous looking (Veneto is one of the richest areas in Italy). I arrive at the Abbazia of San Eustachio, since it is public holiday it has not opened yet. I continue along the road towards Giavera. Every so often, colourful groups of cyclists pass by me – the road round the base of the Montello is particularly popular as a circuit for cycle racing. Apart from some locals driving between the villages and the various churches and cemeteries scattered along the road, there is nobody much else around.

The British Cemetery is well sign posted and up a steep hill from Giavera. It is a beautiful setting, just below an Italian church and adjacent to the local cemetery. You enter along a gravel path lined with olive trees, running through the vineyards. The cemetery contains the remains of 416 identified British casualties, with a memorial stone recording 147 casualties in the area who have no known grave. The although in winter 1917/1918 the sector was fairly quiet by comparison with the Western Front, there are still 230 graves relating to the period from 1st December 1917 to 31 March 1918, when the British Divisions withdrew from the Piave.

The British Cemetery at Giavera

The British Cemetery at Giavera

From the records on the CWGC database, the two worst days for casualties seem to have been 8 December and 11 December 1917 when the Germans and Austrians launched two particularly heavy barrages across the river. Worst affected on the 8th December were the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, who occupied a position flanking the Sherwood Foresters and who suffered 13 killed in the German artillery shoot. Wounded in the barrage was Lieutenant George H Stones of the 11th Battalion Sherwood Foresters who died of his wounds the next day. A further 16 men were killed on 11 December including two Private soldiers from the Sherwood Foresters. Edward Brittain refers to this incident in a letter he wrote to Vera Brittain on 12 December 1917

Grave of Lieutenant GHL Stones of the Sherwood Foresters

Grave of Lieutenant GHL Stones of the Sherwood Foresters

“ We are still in the line which is a much warmer spot than it was when we first arrived in fact we were quite heavily shelled yesterday and I had a man killed. We expect to go out very soon and hope to be out for xmas.. It has come on beastly wet and made the trenches in a most awful state. We are still using our little house as company HQ but we had a shell through one of the rooms yesterday-nobody was in it at the time but a lot of kit was destroyed and if I had been in the next room (where I was 10 mins before ) I should probably have got hit by a piece of wall which got knocked out;”[ii]

Sherwood Foresters who died along the Piave

Casualties in the sector continued at the rate of between one and five a day, presumably relating to men killed on patrol, or in subsequent smaller artillery exchanges. Striking is the number of artillerymen from the Royal Field Artillery, Royal Garrison Artillery, Royal Horse Artillery and Honourable Artillery Company killed on the same days, presumably as a result of accurate counter battery fire hitting their batteries. There are 86 artillerymen interred at Giavera, the vast majority of them gunners. From the CWGC records, you can plot how two or three men from each gun crew were dying at a time, as their batteries were hit by Austrian artillery.

The remainder of the casualties at Giavera and indeed most of the soldiers listed as having no known grave are from October/November 1918 when the British Divisions went on the offensive on the other side of the Piave as part of the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. Also buried at Giavera are nine men from the Royal Flying Corps (later the Royal Air Force) mainly from the 34th and 42nd Squadrons who flew the RE 8 reconnaissance aircraft over the Piave front. There is also Lieutenant Donald McLean, an 18-year Canadian pilot of 45th Squadron whose Sopwith Camel crashed into the Montello in February 1918.

18 year old Canadian Pilot Gordon MacLean of the RFC

18 year old Canadian Pilot Gordon MacLean of the RFC

There is a striking contrast between the British cemetery at Giavera and the Italian Ossario. Understandably, there is a difference in numbers, but the British cemetery reflects the individual soldiers killed, each headstone with a regimental motif, the name and date of death. Some even have message from family or loved ones inscribed. The headstones recognise different faiths; I saw at least two headstones of Jewish soldiers with the Star of David carved into the headstone. It is all more personal and human, than the huge Sacrari where the Italians reburied their own war dead, as part of a memorial to a collective heroic sacrifice rather than individual tragic deaths. The British might refer to “Our Glorious Dead” while still remembering the individual.

Having had a good look round Giavera, I head back in the direction of Nervesa towards the Abbazia de Sant’ Eustachio, hoping that it has opened/ is still open. Good fortune smiles, the Abbazia is still open to the public, so I stroll up the rather steep path, with a vineyard on one side and woods on the other to get to the Abbey.

Abbazia de Sant'Eustachio

Abbazia de Sant'Eustachio

The Abbey has a long and interesting history. Unfortunately, being in a strategic position on the Montello, it found itself in a rather exposed position during the War. Apparently, both British and Italian troops used to camp out in the monastery grounds, when they were in the second line positions on the Montello. I had an interesting chat with Marco, the Manager of the Abbey and its Museum. According to him, British troops had used the altars for firewood and taken pot shots at some of the statues. When the Austrians crossed the Piave and got half way across the Montello during the Battle of the Solstice in June 1918, the Monastery was severely damaged. Finishing the war in a pitiful state, the locals then proceeded to borrow the remaining masonry for their own rebuilding projects and the Abbey finished up pretty derelict.

The results of target practice by British Soldiers

The results of target practice by British Soldiers

While chatting with Marco, he told me one very interesting story. When the British left the Abbey, a British soldier or officer took away a rather important parchment containing a Papal Bull from the 16th Century. This document subsequently resurfaced at Felsted School, a famous British Public School in Essex. The school archivist, Mr Chris Dawkins read about the Abbey restoration project and contacted them, resulting in the eventual return of the precious document to Nevesa. The full story is told on the Felsted School website. Apparently, the bull had been in Felsted School archives for decades, where it was thought to have been bought over to England soon after it was written in the 16th Century. In fact, the document was taken from the Abbey during the First World War. The supposition was that an old Felsted boy, educated in Latin and recognising the document as being valuable had taken it away to safety. The truth is rather more prosaic and Mr Dawkins’ research established that in 1925 the parchment was offered for sale to a dealer in old books and manuscripts, Bernard Quaritch Ltd of London. The managing director of the firm, Mr Roger Dring knew that it had no great financial value, but nevertheless purchased it and gave the document to Felsted School where his sons were pupils. There are two bits of good fortune here. Firstly that a British soldier actually removed it, rather than using it as toilet paper or to stoke the fire and secondly that the keen eyed archivist Mr Dawkins found out the documents true home. So in 2020 more or less a century after it had gone missing the Papal Bull is back in the Abbey and Marco showed it to me hanging in pride of place on the museum wall.

Ermengildo Giusti has funded the whole Abbey restoration project. Giusti emigrated from Italy to Canada in 1975 and made a fortune in the construction business. In 2002, while on a holiday back in Italy, he bought a vineyard. Then he bought some more vineyards, until his company Giusti Wines owned around 14% of the vineyards in the Prosecco DOC area. As well as funding the restoration of the Abbazia, Mr Giusti has also funded a memorial for Canadian Pilot Donald McLean, buried at Giavera cemetery. The crash site of Giusti’s Sopwith Camel was found in one of Giusti’s vineyards.

Giusti Wines

Giusti Wines

Back down on the main road, Giusti wines are putting the finishing touches to a huge new winery and visitors centre which should be opening shortly. In the restaurant at the Abbey visitors centre, I tried a couple of the Giusti wines. Particularly good was a Recantina – Montello- Colle Assolani red, which was smooth and complex and strong, excellent wine. I could not help sharing the story with Marco as to how the British army had tried to discourage its soldiers in Italy from drinking the string local red wines in the same way that they were accustomed to drinking French and Belgian beers.

It has been an interesting couple of days on and around the Montello. The local hospitality has been excellent. Especially the food and wine. Walking along the Piave today, it is all prosperous and peaceful and difficult to imagine, that just as much as the Western Front, this was a place where British soldiers were cold, frightened and hungry- facing an enemy across the other side of that wide expanse of river , not knowing when some random shell fired from the Austrian lines was going to land on them.

Places

Agrifoglio B&B, viale Rimembranza 36 , Nervesa della Battaglia- on booking.com. Very quiet and reasonably priced. Signora Franca and husband Antonio were wonderfully helpful. Antonio picked me up from Susegana Station. Antonio is a former teacher and very knowledgeable on the local area

Frank Baracca – Seafood Restaurant, via Roma, 35 , Nervesa della Battaglia. Excellent seafood and really super pizzas.

Giusti Wine- www.giustiwine.com. The new winery looks like it will be very interesting when it opens to the public.

Abbazia Sant’Eustachio, via Collalto 1, Nervesa della Battaglia. The manager Marco is extremely informative and speaks excellent English too.

Local Map- Carteline Zanetti- Il Montello . Proved invaluable.

To get to Nervesa- the nearest station is Susegana – with a train every couple of hours from Venezia Mestre (direction Udine). From Milan take a direct Frecciarossa from Milano Centrale to Venezia Mestre- or if you fancy a rather slower trip take a regional train from Milano Centrale to Mestre, changing at Verona

[i] Quoted in “Letters from a Lost Generation”, First World War Letters of Vera Brittain and Four Friends “ © Mark Bostridge and Rebecca Williams

[ii] Quoted in “Letters from a Lost Generation”, First World War Letters of Vera Brittain and Four Friends “ © Mark Bostridge and Rebecca Williams