The War in the North of Spain

The Basque provinces of Spain are a very attractive area, as green as Ireland or England and far removed from a vision of the arid landscape of southern Spain ( and thankfully a lower temperature too). The area is easy to access through airports at Santander , Bilbao and Biarritz. Santander, Bilbao and San Sebastián are all different and attractive cities well worth visiting and the food is excellent throughout. I had not expected to find much evidence of the Spanish Civil War , but there were signs - an old air raid shelter in Santander, the sudden discovery of a trench system up the top of the Antxarda Funicular in Bilbao and of course the town of Guernica. It is an area that has strong links with the UK through the maritime trade and as a source of British Iron Ore imports. Digging deeper , I found some interesting British connections especially George Steer the journalist who revealed the horrors of Guernica to the British population and those who did something to bring food aid and evacuate civilians from what became a besieged enclave. In common with the progress of the war, this article starts at San Sebastián , heads to the French border and then back through San Sebastián , Bilbao and Guernica to Santander.

San Sebastián

San Sebastián is a good place to start . It was the birthplace of the Spanish Second Republic, where in 1930 the Spanish Republican parties met to agree on the need for a Republic and signed. the Pact of San Sebastián . There was a certain irony to that since the lovely resort of San Sebastián had been a favored summer retreat for the Spanish Monarchy. The original town of San Sebastián had been sacked and burned down by the British in 1813. In its place an elegant and well planned new city had emerged ,On the other side of the beautiful La Concha beach, they had built the Miramar Palace in English country house style. With its cooler Atlantic climate, San Sebastián became an attractive resort with a Casino, Kursaal and fashionable hotels the Continental and the Londres along La Concha. There were theatres and salt water treatment and in .. the opulent Maria Cristina Hotel had opened. The 1913 Baedeker Guide paints a quick portrait of San Sebastián ( obviously before Spain became a Republic )

San Sebastian in the early 20th Century

“San Sebastian (pop. 43,000), the Basque Iruchulo or Donostiya and the capital of the province of Guipuzcoa, is the summer-residence of the royal family and the most fashionable seaside resort in pain, It occupies an extraordinarily picturesque site at the base of the Monte Urgull. a rocky island now connected with the main- land, and on the alluvial ground between the mouth of the canalized Urumea on the E. and the bay of La Concha on the W. The fortifications were razed in 1866 and since that date a new town has sprung np to the S. of the Boulevard (Alameda), with wide streets and handsome promenades.

The most fashionable resorts are the promenades skirting the Concha, a noble bay bounded by the Mte. Urgull on the N.E. and the Mte. Igueldo on the W., while the small island of Santa Clara shelters its outlet on the N.W. Here is situated the Casino bounded on the E. by the Alameda and on the S. by the park of Alderdieder , which is continued by the Paseo de la Concha The beach is excellently adapted for bathing. The Caseta Real is the bathing-house of the royal family. above a tunnel threaded by the road to the suburb of Antigua is the unpretending royal Palacio de Miramar (built in 1889-93 from the designs of the English architect Selden Wornum.“

The Spanish Second Republic got off to a difficult start . From being dominated by Centrist parties in 1931, matters began toi be progressively more polarized. Political violence increased, with an attempted Revolution in 1934, which involved considerable blood letting. Although the Popular Front Government restored some semblance of order, the violence continued, culminating in the assassination of opposition leader Calvo Sotelo by leftist elements. This was the catalyst for a military rebellion, in Spanish Morocco, which spread to Military Garrisons in other parts of Spain. Rather than a quick military coup, the military rebellion was resisted by the population starting a civil war. The Basque provinces in the north were cut off from the Government in Madrid by a large swathe of territory held by the rebels. Geographically the north was cut off from the rest of Spain controlled by the legitimate government, with access only by the border to France and by sea.

Strategically the rebels, needed to strangle the Basque country by cutting off the crucial link to France . The first Northern campaign was conceived by rebel General Emilio Mola as an advance to Irún, to cut the northern provinces off from France, and to link up with a rebel garrison which was holding out in San Sebastián. The campaign was diverted from the advance on Irún when the direct route to the town was blocked by the demolition of the bridge at Endarlatsa. With the rebels in San Sebastián besieged in the Cuartel de Loyola, the rebel commander Alfonso Beorlegui diverted all his forces there an attempt to relieve them.

One of the best descriptions in English of events in San Sebastián is given by the US Ambassador to Spain, Claude G Bowers. Bowers was a “New Deal” Democrat appointed to the role by Roosevelt, he was also a former journalist which shows in the fine quality of his writing. Bowers was an ardent advocate for both the Basques and the legitimate Government of Spain. Although he might technically have started as a non-interventionist, it is clear from his memoirs that he rapidly departed from that path. Untypically for American diplomats, Bowers actually backed a legitimate Left wing Government against Right Wing military rebels. Presciently he foresaw German and Italian intervention in Spain as a dress rehearsal for the Second World War.

When the rebellion started , Bowers was in San Sebastián. The Spanish Monarchy had previously decamped to San Sebastián as a summer capital, and the diplomatic corps had traditionally followed . Bowers has taken a villa at Hondarribia (Fuenterrabía); a town situated on a little promontory facing Hendaye in France. A boat makes the trip between the two cities. The town holds an ancient old quarter with walls and a castle. From there Bowers had a handy commute to the United States Summer embassy at the Continental Hotel in San Sebastián. He was there when he heard rumours of an attempted coup in Madrid, the situation in San Sebastián was confused and communications interrupted.

Hondarribia (Fuenterrabía) viewed across the estuary from France

In July 1936 the military garrison of San Sebastián was made up of the 3rd Heavy Artillery regiment, commanded by Colonel León Carrasco Amilibia —who was also military commander of the province— and the 6th Battalion of Sappers, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel José Vallespín; both units were stationed at the Loyola Barracks, the main military barracks in the city. Carrasco, despite being a monarchist, had recently joined the military conspiracy and did not have the confidence of General Mola. To start with his position was equivocal. The civil government of Guipúzcoa was in the hands of the republican Jesús Artola Goicoechea, while a large part of Guipúzcoa was sympathetic to Carlism ( a rig hewing monarchist faction which allied with the rebels ) , the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) – a Catholic and conservative formation remained loyal to the Republican Government although having important ideological differences with the members of the Popular Front.

On 18 July, 1936 the news of the military rebellion in Spanish Morocco and in nearby Navarre reached San Sebastián, left-wing unions such as the CNT and the UGT decided to mobilize their members, demanding that the civil governor of San Sebastián hand over weapons for their groups. On 19 July the military garrison of the city of nearby Vitoria joined the uprising and the demand of the workers' organizations became impossible to ignore. In Guipúzcoa the forces of the Civil Guard, the Assault Guard, the Carabineros Corps and Migueletes (police of the Guipúzcoa provincial council) expressed their loyalty to the government of the Republic – with the exception of Colonel López de Ogayar, who supported the military rebellion. Colonel Carrasco maintained an ambiguous attitude towards the rebellion, however on 19 July, he was arrested when he went to the civilian government to supposedly protest the shooting of army officers. Lieutenant Colonel Vallespín took control of the situation, but throughout the 20th remained in total passivity lacking the support of the officers of the garrison. Meanwhile, the workers' militias began to take control of the streets of San Sebastián.

The news from other parts of Spain convinced the civil authorities of San Sebastián of the urgency of gathering a column of troops to join the volunteers of the CNT and UGT who were preparing to leave for Vitoria, led by Commander Augusto Pérez Garmendia, a vacationer in the city who had put himself at the service of the Republican authorities. The support column formed by CNT workers, civil guards and assault guards was organized to leave for Vitoria that same afternoon. Meanwhile Vallespín, pressured by Mola, decided to join the military uprising. On 21 July, after the departure of the column to attack Vitoria, Vallespín gave the order for troops to join the rebels and leave the Loyola Barracks and take strategic points in San Sebastián . The rebels placed two pieces of artillery in front of the government offices , causing their occupants to flee and allowing the imprisoned Colonel Carrasco to escape. After a brief fight the rebel troops took control of the most important buildings in the city, while the Republican authorities and many trade union leaders immediately fled to Éibar, where they made contact with Pérez Garmendia's column. The freed Colonel Carrasco established his centre of operations in the María Cristina Hotel, declaring a state of war, while the group of Civil Guards who joined the rebellion concentrated in the Gran Casino.

On 22 July at Eibar, Pérez Garmendia learned of what had happened in San Sebastián and immediately planned the recovery of the city, he left a small fraction of his forces there and returned with most the column to San Sebastián, supported by the loyal elements of the Guardia Civil, the Assault Guard, the Carabineros and the Migueletes. After a day of heavy fighting , by dusk the rebels retained only the Loyola Barracks and the María Cristina Hotel, while the government security forces and militia recaptured the rest of the city. At the Hotel Maria Cristina the rebels had evicted the remaining holidaymakers and barricaded themselves in, allegedly using some of the remaining holidaymakers as human shields . The fighting at the hotel caused serious casualties to the loyalists but the rebels entrenched in the hotel were finally defeated and the building was occupied by loyalist forces.

The Gran Casino - now the town hall in San Sebastian

The Maria Cristina Bridge with the Maria Cristina Hotel in the background

Outside the city centre , the rebels held on at the Loyola Barracks which contained a sizeable armoury, with around 1700 rifles and machine guns and eight howitzers, which would have allowed them to prolong the resistance for an almost indefinite time. However, from the morning of 24 July, the loyalist forces began to surround the Barracks. Although outgunned the anarchist militia were far superior in number and imposed a close siege on the barracks, the arrival of the Civil and Assault Guards increased pressure on the rebels whose position was undermined by the continued indecision of Colonel Carrasco Amilibia as to whether to continue with the revolt or surrender. On 28 July the rebels at Loyola surrendered, Colonel Carrasco Amilibia was taken prisoner by the anarchist militias along with several other officers who at first joined the revolt. Despite the fact that his position had been the main factor for the failure of the revolt in San Sebastián, Carrasco was murdered without having had the opportunity to testify in court, his body being dumped near the railway tracks, in the Amara neighbourhood, Despite the efforts of the civilian government, controlled by the PNV, to take control of the barracks' arsenal, the anarchist militias beat them to it and obtained most of the weaponry, thus manifesting the first tensions between the PNV and the left-wing unions. On the night of 30 July, the Ondarreta prison was stormed by militiamen, killing several dozen right-wingers and "rebel" army officers. On August 6, the inefficient Artola Goicoechea was dismissed and replaced in the civilian government by the lieutenant of the carabineros Antonio Ortega Gutiérrez.

While these violent events played out in San Sebastián , the diplomatic corps safely exiled in France seemed to think that a rebel victory would come fairy quickly, Bowers was in a minority in understanding that would not happen if the people defended the legitimate government.

Even though the situation San Sebastián was calming down, Bowers was pressured to leave Hondarribia for the safety of Hendaye. Under protest he made the short motor boat trip to France making for the Golf Hotel in St Jean-de- Luz. There he was asked to join the USCG cutter Cayuga ( which had been lent to the US Navy) and formed part of the Spanish Squadron tasked with evacuating Americans from Spain. The Cayuga sailed to Bilbao, where Bowers discovered that Fake News was already spreading in Spain; rumour had it that the government intended to seize the American Firestone plant in Bilbao, together with its secret chemical formula and process. In a perfectly pleasing interview with the local governor, Bowers found that American Executives were welcome in Spain and that the loyalist government in Bilbao merely needed to procure tyres from Firestone. Matter resolved the Cayuga proceed to Vigo then Coruna, Gijon and on to Santander picking up stray Americans on the way. When they could not find stray Americans , they evacuated Cubans or Argentines who wanted to leave. By the time they got back to San Sebastián, loyalist forces were firmly back in control. He was annoyed that some of the American evacuees started spreading exaggerated stories on landing, about seeing all the towns and villages along the coastline in flames. Boers reflected ion that cruise aòong the -northern coast

“The towns were enveloped in tragedy, silent, grim and mostly sad. The people we rfeady to die, if need be, but it seemed so hopeless. This corner was completely shut off from any possibility of assistance from the loyalist government of Madrid”

Irun

The old International Bridge between Irun and -Hendaye

Back in France, Bowers established the US Embassy at the Eskladuna Hotel; on Hendaye Plage, although he continued to cross frequently to his home in Hondarribia . Time was however running out. On 26 August . Beorlegui began the assault on Irún, the frontier town of vital strategic importance. The Spanish Government’s perfectly legitimate arms purchases from France were trucked across the International Bridge to Irun. From the Eskladuna Hotel across the bay, Bowers could observe the rebel assault,. The city was bombed from the air while the rebel naval ship Cavera shelled it from offshore. Loyalist troops continued to hold the strategic fortress of Guadalupe, which commanded the high ground overlooking Hondarribia. A ground assault on Irun commenced, with waves of Foreign Legionaries assaulting the fortress and mainly being killed in repeated attacks. The poorly armed and untrained leftist and Basque nationalist militias fought bravely but could not fend off the rebel push, in no small part due to an inability to get ammunition to the defending forces.

A view across to the Eskladuna Hotel in Hendaye which provided a refuge for diplomats fleeing Spain

Before the assault the British had strong-armed the French into banning arms supplies to the Spanish Republic.. Draft declarations had been put to the German and Italian governments.. An ultimatum was put to Yvon Delbos by the British to halt French exports to Spain, or Britain would not be obliged to act under the Treaty of Locarno if Germany invaded. On 7 August 1936, France unilaterally declared non-intervention and two days later exports were duly suspended. However, supplies of food, clothing and medical supplies to the Spanish Republic . After bloody fighting, the defenders of Irun were finally overwhelmed on 3 September: thousands of civilians and militia-men fled in panic, some across the French border. The town was occupied by rebel forces later that day and retreating anarchists burned parts of it to the ground. As Bowers puts it.

International road and rail bridges between Spain and France - before the Non Intervention pact, perfectly legal arms purchases from French government crossed the bridge,

“at a critical state of the battle of Irun the lorries with arms and ammunition for the defenders ceased rolling across the International bridge, and the loyalists were left naked to their enemies. What Mola had not accomplished had been done for him by the nonintervention pact, concocted by the governments of democratic peoples. “

After the rebels captured Irun the capture of San Sebastián became more or less inevitable, A sizeable number of the city's 80,000 inhabitants fled on an exodus towards Bilbao or crossed into France. British field-journalist George L. Steer sets the figure of the population fleeing to at 30,000. PNV officials arranged for the final orderly evacuation of the city before its fall, holding back anarchist efforts to repeat the burning of Irun by shooting several anarchist officials. The rebels advanced further west until they were stopped by the Republicans at Buruntza for a few days, but continued their push until the outer fringes of Biscay (Intxorta). There, the resistance of the Basque pro-republican forces, along with the exhaustion of the Nationalists, resulted in an end of the offensive until the War in the North began In a few months in late 1936 the rebels conquered 1,000 square miles of terrain and many factories and cut off the Basques from their land-links with a sympathetic France. In rebel occupied territory, a Comisión Gestora or Management Commission was appointed by the rebel nationalists comprising the factions involved in the military insurrection, i.e. Carlists, Falangists, and others. The Junta Carlista, the Carlist high executive body in the province, was then chaired during the first months by the local Carlist leader Antonio Arrúe Zarauz up to early 1937.Speaking in the Basque language was forbidden by proclamation. Occupation was followed by harsh repression against inconvenient figures and individuals. The Basque clergy were specifically targeted and exposed to torture and rapid execution for their family ties and/or proximity to Basque nationalist proponents and ideas. In general, they were searched according to blacklists put together in Pamplona. Occasional protests from the ecclesiastic hierarchy did not go far and a widespread purge of the clergy in Gipuzkoa was decided in the high military and ecclesiastic circles. The occupiers also purged the Provincial Council (Diputación/Aldundia).

The War in the North

Things then stayed quiet for six months until on 31 March 1937, the Francoist forces, led by Mola, started their offensive against the , Vizcaya Province. Mola said that:

"I have decided to terminate rapidly the war in the north: those not guilty of assassinations and who surrender their arms will have their lives and property spared. But, if submission is not immediate, I will raze all Vizcaya to the ground, beginning with the industries of war".

The war in the North

By that time, the Italians and the Germans had abandoned any pretence at non-intervention. After the failure of Franco's offensive on Madrid, Mussolini decided to send regular army forces to Spain. General Mario Roatta was made the Commander-in-Chief of the Italian "expeditionary force". General Luigi Frusci became his Deputy Commander. On 23 December, The first formation of 3,000 troops landed in Cadiz and was called the "Italian Army Mission". By January approximately 44,000 regular Italian army soldiers and Fascist paramilitaries were in Spain. In late February, the "expeditionary force" was renamed the "Corps of Volunteer Troops" (Corpo Truppe Volontarie, or CTV). The Blackshirt (Camicie Nere, CCNN) Divisions contained regular soldiers and volunteer militia from the National Fascist Party. Between 3 and 8 February, the 1st CCNN Division "Dio lo Vuole", supporting the Francoists, launched an offensive against Málaga and captured the city. By March the CTV numbered over 50,000 troops. Mussolini decided that Fascist Italian forces should lead a fourth offensive on Madrid. The Italian offensive resulted in the Battle of Guadalajara, which ended as a decisive victory for the Republican forces. In contrast, the Italian forces suffered heavy losses.. The Italian offensive was repulsed by a strong Republican counter-offensive led by the 11th Division. Of the four Italian divisions engaged, only the Littorio Division did not suffer heavy losses. The three CCNN divisions had such heavy losses that they had to be reorganised into two divisions and a special weapons (armour and artillery) group. Subsequently the Italian forces were sent to support the offensive in the North.

The same day the Francoists bombed Durango, a town of 10,000 inhabitants at a road and railway junction between Bilbao and the front. By bombing the road and infrastructure in the town, the Republican forces would be prevented from sending reinforcements from Bilbao and their potential line of retreat would be blocked. Despite the importance of Durango as a transportation junction, the town had no air defences, and there were few Republican fighter planes to be found in the Basque region. German Ju 52 and Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 transport planes modified to carry bombs from the Condor Legion and the Aviazione Legionaria bombed the town in relays. Two churches were bombed during mass, killing 14 nuns and the officiating priest. Heinkel He 51 fighters strafed fleeing civilians. Altogether, around 250 civilians died in the attack. On 28 April, Durango fell to Nationalist side. While the local road junction might have meant that Durango was a legitimate target for an air attack and the bombing did not contravene the laws of war as they were at the time, foreign observers were shocked at the carnage. The Nationalists denied responsibility for the bombing, claiming that the priest and the nuns who died in the bombing were killed and burned by the reds. The bombing of Durango was to a certain extent overshadowed by the bombing of Guernica.

Guernica

Gernika

Guernica (Gernika in Basque), 30 kilometres east of Bilbao, a town of 7,000 people was a centre of great significance to the Basque people. Its Gernikako Arbola ("the tree of Gernika") is an oak tree that symbolises traditional freedoms for the Biscayan people and, by extension, for the Basque people as a whole. Guernica was considered a key part of the Basques' national identity; “the home of Basque liberties”. It was also the location of the Spanish weapons manufacturer Astra-Unceta y Cía

The Peace Museum in Gernika

Thanks to the Germans and Italians, the rebels could deploy, two Heinkel He 111s, one Dornier Do 17, eighteen Ju 52 Behelfsbomber, and three Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie . These were armed with 250 kg medium high-explosive bombs, 50 kg light explosive bombs and 1 kg incendiaries. The ordnance load for the 24 bombers was 22 tonnes in total. A follow-up to the bombing raid was also planned for the next day involving Messerschmitt Bf 109 raids in the area.

The first wave arrived over Guernica around 16:30. A Dornier Do 17, coming from the south, dropped approximately twelve 50 kg bombs. The three Italian SM.79s took off from Soria at 15:30 with orders to "bomb the road and bridge to the east of Guernica, in order to block the enemy retreat" during the second wave. Their orders explicitly stated not to bomb the town itself. During a single 60-second pass over the town, from north to south, the SM.79s dropped thirty-six 50 kg light explosive bombs. It appears that the Italians may have limited their involvement in the bombing, since they were negotiating with the Basque Government through the offices of the Vatican at the time. The next three waves of the first attack then occurred, ending around 18:00. The third wave consisted of a Heinkel He 111 escorted by five Regia Aeronautica Fiat CR.32 fighters led by Capitano Corrado Ricci. The fourth and fifth waves were carried out by German twin-engine planes. The 1st and 2nd Squadrons of the Condor Legion took off at about 16:30, with the 3rd Squadron taking off from Burgos a few minutes later. They were escorted from Vitoria-Gasteiz by a squadron of Fiat fighters and Messerschmitt Bf 109Bs of 2. Staffel ,Jag Gruppe 88 (J/88), for a total of twenty-nine planes.

An incendiary bomb of the type the Germans dropped on Gernika

An air raid siren from the Peace Museum in Gernika

High Explosive bomb of the type dropped on Gernika

The attacks destroyed the majority of Guernica. Three-quarters of the city's buildings were reported completely destroyed, and most others sustained damage. Among infrastructure spared were the arms factories Unceta and Company and Talleres de Guernica along with the Assembly House Casa de Juntas and the Gernikako Arbola. The number of civilian fatalities is now set at between 170 and 300 people. Until the 1980s, it had been generally accepted that the number of deaths had been over 1,700, but these numbers are now thought to have been exaggerated. The Basque government, in the confused aftermath of the raids, reported 1,654 dead and 889 wounded. Such a number roughly agreed with the testimony of British journalist George Steer, correspondent of The Times, who estimated that 800 to 3,000 of 5,000 people perished in Guernica. The rebels continued to give a patently false description of the events, claiming that the destruction had been caused by Republicans burning the town as they fled, and seemed to have made no effort to establish an accurate number. As late as 1970 the Francoist press continued claimed, on 30 January 1970, that there had only been twelve dead.

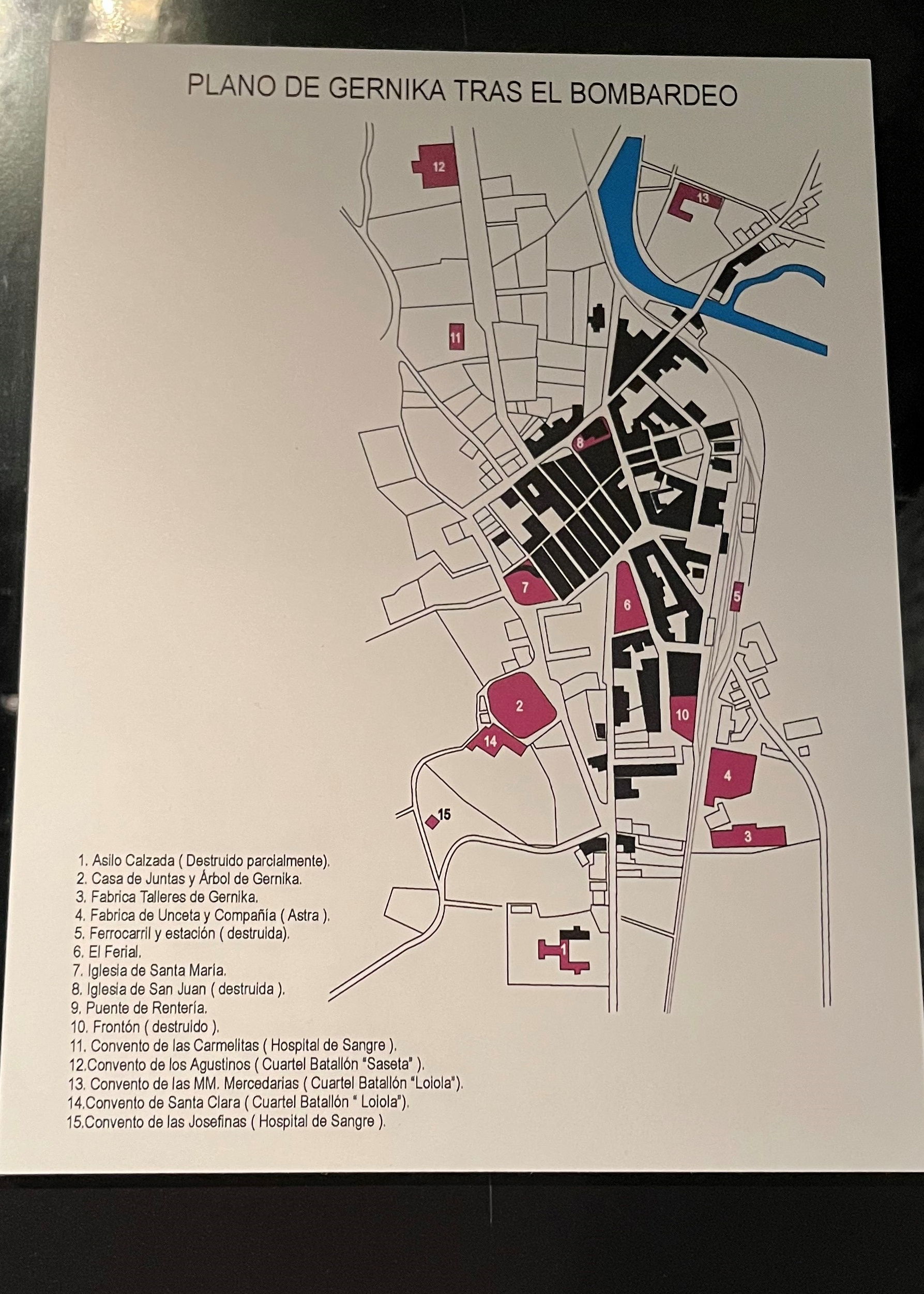

From the Peace Museum in Gernika -a map of the destruction of the city

The bombing shattered the city's defenders' will to resist, allowing the rebels to overrun the town. The rebels faced little resistance and took complete control of the town by 29 April.

A replica of Picaasso's famous work in Gernika

Bilbao

The next major city to be threatened was Bilbao, the economic centre of the Basque Country. During the 19th century extensive iron ore deposits were discovered in the nearby hills, which boosted the area's industrial base. The estuary of Bilbao was covered by steel and shipbuilding industries and the docks expanded from Bilbao to the bay. All activity relied on the navigability of the river so engineer Evaristo Churruca developed an enormous project that would solve the navigation problems of the river. The river banks were drained and docks were built, the river's course was straightened, the external port was enclosed, and the Puente Colgante transporter bridge was built. By 1900 Bilbao was Spain's biggest port.

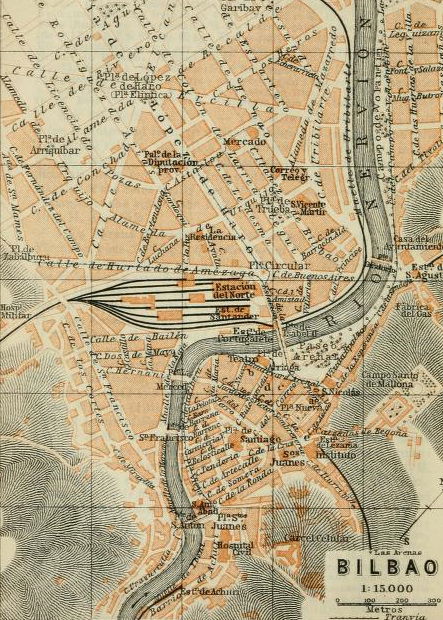

Bilbao in the early 20th Century

The railway arrived in the city and the Bank of Bilbao (later BBVA) was founded, as well as the Bilbao Stock Exchange. Steelmaking industries flourished with the creation of many new factories, including the Santa Ana de Bolueta and the Altos Hornos de Vizcaya in 1902. The city was modernised with new avenues and walkways, as well as with new modern buildings such as the City Hall building, the Basurto Hospital and the Arriaga Theatre. The population increased dramatically, from 11,000 in 1880 to 80,000 in 1900. Social movements also arose, notably Basque nationalism under Sabino Arana, which in the subsequent decades would grow to become the PNV. The Old Town on the right bank of the river Nervion, with its narrow streets was closely packed between the river and the hills. The New Town, on the roomier left bank, developed following the Carlist wars, grew much larger than the old town, with which it is connected by five bridges. With the river canalized, ships of 4000 tons could reach the centre of the city , while a large outer harbour has been constructed at El Abra, at its mouth.

As mentioned, Bilbao owed its prosperity mainly to iron ore. In the middle ages Bilbao was so celebrated for its iron and steel manufactures, that the Elizabethan writers use the term bilbo for rapier and bilboes for fetters. Thus Falstaff ('Merry Wives of Windsor', III. 5) describes his condition in the buck-basket as 'compassed, like a good Bilbo, in the circumference of a peck, hilt to point, heel to head'. It was the iron ore trade which developed Bilbao’s links with the United Kingdom, Of the 188 million tons of iron ore imported into the UK between 1871 and 1914, 150 million tons, or nearly 80% came from Spain. The problem confronting UK steel manufacturers in in the early 1870's was securing long-term sources of supply of non-phosphoric iron ore at normal prices. Domestic hematite mines were unable to meet demand and the only solution to the problem lay in the importation of non-phosphoric ore. Throughout the 1860's, there were small imports of Spanish iron ore mainly to ironworks in South Wales, where local supplies were exhausted. The North-East made trials with Spanish hematite ore in 1861. But as late as 1869, only 131,000 tons of iron ore were imported into the United Kingdom, representing a mere 12 per cent of total ore consumption. By 1910-14, about 43 per cent of all pig iron produced in the United Kingdom was manufactured from imported ore. The most important of Britain's iron and steel producing districts were near to ports-in the North-East, the North-West, in Scotland and South Wales. To lower freight costs to the smelting plants, it was necessary that the overseas iron mines were similarly situated near to seaports. Only one major European deposit of iron ore answered all requirements- northern Spain, with the ports of Bilbao, Santander, Castro-Urdiales and San Sebastian. The rich hematite ore lay in compact masses and could be mined by open-cast operations. In 1870, a heavy export duty on iron ore, hitherto a serious bar to the expansion of the export trade in Spanish iron ore, was removed altogether for a period of ten years. So by 1871, a combination of circumstances both in the United Kingdom and in Spain attracted British steel and mining companies to the iron mining district surrounding Bilbao.

A view of the river Nervion in the 1920s

The same view in 2024

In 1871, the British Consul in Bilbao reported on a chaotic state of affairs which where the demand for the rich hematite ores of the district exceeded not only the ability of the producers to supply the quantities and the limited quayside facilities. Although matters improved, by the early twentieth century, when the British steel industry gradually turned to the more general use of the Thomas basic process, its dependence on supplies of non-phosphoric ore declined. The importance of the Spanish source of ore waned, and the export of ore from Spain fell off rapidly after 1918, Spanish iron ore from nearly 90% of all iron ore imported into the United Kingdom in the peak year of 1899, accounted to around 60%. Although British investment activity in the Spanish iron mines by no means ceased by 1937,Spanish ores only accounted for 13% of total British imports of iron ore, with trade continuing with the North East.

The river Nervion in 2024

The civil war in Bilbao started with a number of small uprisings suppressed by the Republican forces. On 31 August 1936, the city suffered its first bombing, with a series of air bombs dropped by rebel airplanes. In September, the rebels distributed pamphlets threatening further bombing if the city did not give up, which finally took place on 25 September when German planes, in coordination with Francoist forces, dropped at least a hundred bombs on the city. In early October 1936, after the fall of Gipuzkoa into the hands of the rebel troops and the consolidation of the Basque resistance, the Bizkaia Defence Board acknowledged the need to provide Bilbao and its immediate surroundings with defensive works as protection in the event a new attack by Franco’s army managed to break the established front line. Days later the recently-formed Basque Government presented the draft. José Antonio Agirre, then defence counsellor, along with the head of the Basque Government, commissioned Engineering Commander Alberto Montaud to undertake the construction of Bilbao’s Defensive Ring,

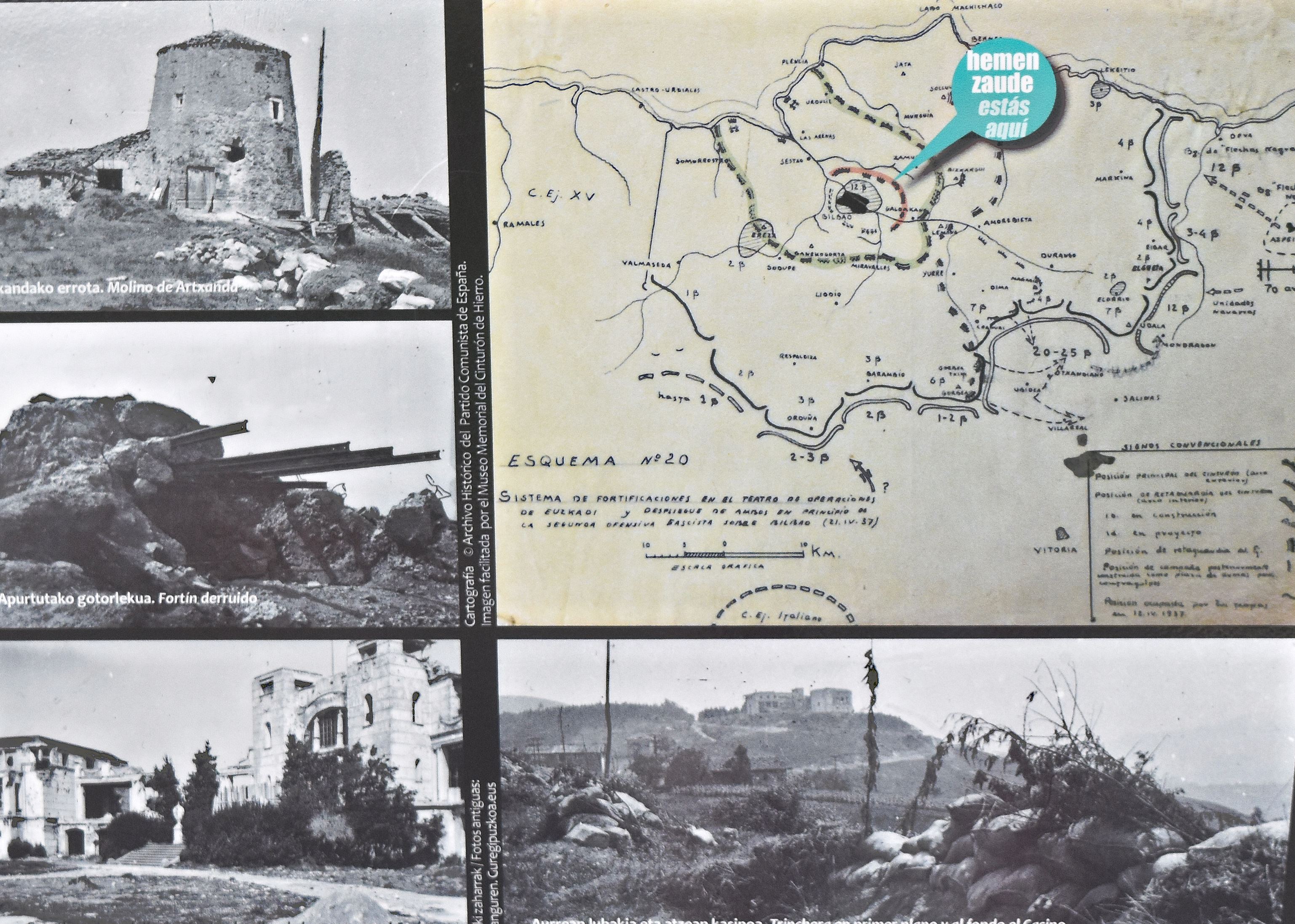

Map of the defensive lines around Bilbao

This vast fortification consisted of a ring of trenches, machine-gun positions, strongpoints and secret bunkers. The Ring was divided into five sectors running along the route Zierbena – Sodupe – Miraballes – Usansolo – Larrabetzu – Barrika, the city of Bilbao, the Lamiako and Sondika aerodromes, the harbour with battery emplacements at Punta Galea and Punta Lucero, the Zollo reservoir, and the power station at Burtzeña lying within its borders. It covered overall a perimeter of 80 km over the mountains around Bilbao, defended by 45 000 gudaris and militia members of the Army of the Basque Country.

The works were carried out by some 10 000 labourers. Montaud also relied on professional assistance from a couple of military officers, who professed loyalty to the Republic but supported the rebels. Captain Pablo Murga, acted as an informant for an espionage network directed by the Austrian consul, and was subsequently tried and executed. Captain Alejandro Goicoechea, changed sides on 27 February 1937 and informed the rebels about the location and construction details of all defensive elements of the Ring. So the Francoist troops learned enough about the infrastructures under construction. Only 40% of it had been finished by the time of his desertion, according to Goicoechea. He also supplied valuable information concerning the location of three unfortified sites where the Ring could be breached and broken. It was precisely at one of those sites, between Mounts Gaztelumendi (Larrabetzu) and Urrusti (Gamiz-Fika), the rebels attacked.

The Royal Navy in Spanish Waters

In April 1937 the question of Northern Spain and the blockade began to become of pressing concern for the British, and especially the question of how to protect British Merchant Shipping. Back in the 1930s, the British merchant Fleet was the largest in the world, shipping was vital to the British economy and the protection of the British Merchant Fleet was one of the responsibilities of the Royal Navy. The matter hinged on the question of belligerent rights and non- intervention. Although the Republic was the legal government of Spain, the British felt that giving the legitimate government blockade rights against the rebels would contravene the nonintervention agreement, either both sides got blockade rights or neither. The risk of giving blockade rights to the Republic was that they used these rights to blockade German or Italian ships, thus precipitating a wider conflict. So far the Republic had not used blockades , but as the rebels launched their offensive in Northern Spain, Franco announced a blockade of the northern ports .

Although the Government Navy was far larger, the rebels were able to rely on the battleship Espana , the cruiser Almirante Cervera and the destroyer Velasco which had deserted to the rebel sides for blockade duties. British policy was that no Spanish ship would be allowed to stop any British ship on the High Seas . This did not apply to Spanish territorial waters ( the three mile limit of the Northern Spanish coat ). The Basque government possessed powerful coastal artillery which kept the rebel naval vessels out of reach and they also regularly swept the waters for mines. With the Royal Navy protected British ships until they reached territorial water, Franco’s blockade was unlikely to be particularly effective. Since British ships were forbidden by law to carry war matériel to Spin and the Royal Navy had the right to search them, it was pretty clear that British ships sailing to northern Spain, would be carrying only food, raw materials or humanitarian supplies. As the rebel stranglehold choked Northern Spain, supplies began to run short in Bilbao, some British ships continued to run the blockade.

The Royal Navy had been involved in Spain , since the military rebellion had left some two thousand British citizens stranded in the country. By 24 July , fifteen British warships were in Spanish ports to lead the evacuation. By the end of October, they had evacuated 11,195 people, the majority of whom were not British. In addition British ships were involved in exchanges of Spanish citizens between the warring sides and under the auspices of the International Red Cross. The Royal Navy transported 17,000 Spaniards on both sides to safety. The Royal Navy’s work in Spanish waters was not without risk, a number of British ships were accidentally bombed starting with HMS Blanche in August 1936. The main danger was mines, to which the thin hulled British destroyers were particularly vulnerable.

Although the Royal Navy acted with impeccable impartiality, its officers seemed to have got on amicably enough with the officers of Franco’s rebel navy. A number of senior Spanish naval officers had sided with the rebellion, unfortunately for them most of the junior officers, NCOs and men did not and many of the rebellious officers were dispatched without much in the way of due process. British -naval officers contrasted the professional officers of the Francoist navy, with the disorganization of the government and the auxiliary Basque Navy. Whatever their sympathies, the Royal Navy officers rigorously obeted the orders of the British government.

The first six months of the Royal navy’s operations in Spanish waters were quiet until the rebel offensive started in the north. With the rebels trying to starve the population out, the Basque government had chosen British ships to bring in food and had paid for the services on the premise that the British would protect their own ships. The trouble was that aiding food supplies into the north and effectively breaking the rebel stranglehold on the north could be construed as taking sides. The British government came up with a typical fudge by warning British shipowners that entering Bilbao was too dangerous. The Foreign office and the Admiralty took opposing views. The Prime Minister, Stanly Baldwin was then forced to defend the position on the House of Commons.

British policy was that no Spanish ship would be allowed to stop any British ship on the High Seas . This did not apply to Spanish territorial waters ( the three mile limit of the Northern Spanish coat ). The Basque government possessed powerful coastal artillery which kept the rebel naval vessels out of reach and they also regularly swept the waters for mines. With the Royal Navy protected British ships until they reached territorial water, Franco’s blockade was unlikely to be particularly effective. Since British ships were forbidden by law to carry war matériel to Spin and the Royal Navy had the right to search them, it was pretty clear that British ships sailing to northern Spain, would be carrying only food, raw materials or humanitarian supplies. As the rebel stranglehold choked Northern Spain, supplies began to run short in Bilbao, some British ships continued to run the blockade.

Matters came to a head, on the morning of April 6th, the British merchantman Thorpehall, was heading to Bilbao from Alicante with a cargo of rice and other food for the starving population of Bilbao. Thorpehall reported by wireless that she had been fired upon by an armed trawler, the Galerna while still eight miles from the coast. The British destroyer H.M.S. Brazen, patrolling nearby, went to investigate. As she approached, her crew at action stations, the rebel cruiser Almirante Cervera also arrived in the area to support her. Brazen’s captain, Cdr. R. M. T. Taylor, placed his ship between Thorpehall and the Spanish cruiser while protesting that the merchantman had been interfered with outside of the recognized three-mile limit. Almirante Cervera backed off to wait near the territorial limit and capture Thorpehall when she tried to enter Bilbao. Later in the morning, H:MS Brazen was joined by the destroyers H.M.S. Blanche and H.M.S. Beagle, the three British ships placed themselves between Thorpehall and Almirante Cervera with crews at action stations, and shepherded the merchant vessel to Bilbao

On 7th April, the British Cabinet met .The First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir Samuel Hoare , who was generally a supporter of Franco wanted to give belligerent rights to both sides . The Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden was broadly sympathetic to the Basques and not in favour of any blockade. Public opinion sided with Eden and the RN was forced to reinforce the fleet in the Bay of Biscay , with the battlecruiser HMS Hood. I was made it clear to Franco, that firing on a British ship would result in the rebel navy being sunk. Unfortunately having found a bit of spine the British Government then fudged the issue by advising the Merchant Fleet that there were dangers in approaching Bilbao and the RN could not protect them in territorial waters.

The Newcastle ship Hamsterley was already on her way to Bilbao, having left Antwerp with a cargo of peas and beans on 3rd April .After receiving an Admiralty warning that protection was not guaranteed, Captain Still retreated to the French port of St Jean de Luz. Hamsterley joined several other British ships waiting in the hope of Navy assistance to get through the blockade .Soon after the Welsh ship Seven Seas Spray successfully made a solo dash from St Jean de Luz to Bilbao with food, arriving on 20th April. with HMS Hood now on station, the British government authorised the Navy to give more protection to British ships breaking the blockade.

The British Battleship HMS Hood which was sent to defend bRitish shipping in International waters

Hamsterley joined a small convoy with Stanbrook, which had sailed from Blyth, and the MacGregor and headed for Bilbao. H.M.S. Fearless and the battlecruiser H.M.S. Hood, were on station nearby. The Galerna and Almirante Cervera, fired warning shots toward the merchantmen while the ships were outside the territorial limit. When Admiral J.F. Blake, aboard Hood, protested the Spaniard’s actions, the Cervera’s commander replied, claiming a six mile territorial limit. Admiral Blake stationed Fearless at the three mile limit as an indicator to the Spanish of where they could conduct their blockade. Faced with overwhelming force on the one hand and the possibility of mine fields and shore batteries on the other, the Spaniards backed down and eventually allowed the three merchant ships through under the watchful eyes of the British squadron. Hamsterley had a Daily Express reporter on board. He gave a vivid description of their journey as they neared Bilbao (Daily Express, April 24th):

"We were now leading the convoy, but we had gone only a few yards when the trawler, the Galerna, fired right across our bows. The shell skimmed across the deck very low and plunged into the sea a bare fifteen yards away. Captain Still cursed aloud, and banged his fist on the bridge rail. “Stop her, quartermaster!” Another signal fluttered from the destroyer’s mast: “Proceed, Hamsterley.” Captain Still fairly bellowed through the megaphone to the Stanbrook, just astern: “Come on, my lads! Follow me into Bilbao.” … 8 a.m. – Shell from shore battery has just fallen a bare six feet short of the Galerna. Galerna turned in her own length, and, dodging between the Hamsterley and MacGregor, scuttled off to safety… The British ships were given a tremendous welcome when they berthed up in the town this afternoon. They arrived in the middle of an air raid, but hundreds of people came from their shelters to cheer the blockade-runners. The raiders came in batches of nine; since yesterday they have dropped 500 bombs."

Saving Basque children

As the conflict intensified in the Basque country, the Basque Government appealed for foreign governments to accept child refugees for what they wrongly thought would be only a few months until the rebels were overthrown. The governments of France, Russia, Belgium, Mexico, Switzerland and Denmark between them accepted almost 29,000 child refugees. The British Government taking the policy of Non-Intervention Agreement to an extreme initially refused to accept any refugees.

Dame Leah Manning who organised the salvation of Basque children

Key to evacuating the Basque children from Bilbao was Leah Manning. In April , she had been fund raising for medical assistance to Spain, returning home one evening she found a representative of the Basque Delegation in London, who asked for her help in facilitating the evacuation of children from Bilbao. The Basques arranged for Leah to fly to St Jean du Luz and from there she took another flight across rebel held territory to Bilbao. She arrived on 24 April and went straight to the British Consulate, on finding that she refused to leave , the British Consul Mr. Stevenson, somewhat reluctantly agreed to help her. Leah was in Bilbao when Guernica was bombed and arrived at the town to see the aftermath of the raid.

“We drove over that night, to find such a scene of utter devastation as will be printed for ever on our minds. It cannot be described in words; only Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ can depict its stark horror. If this raid was intended to destroy the morale of the people it utterly failed in its purpose. Bitter hatred against the Germans, who were responsible, and against non-intervention controls, which were to operate from the end of that month, filled the hearts of the people with a cold fury. Morale stiffened and, for the time being at least, this led to a heart-warming spurt in the rebuilding of defences, a task in which all might take part.”

On her return to Bilbao, Leah often went out at night to help in the work of strengthening the ‘Inner Iron Ring’. Since the work was sometimes within talking distance of the enemy,she was issued with a permit to carry arms. In those days there was some hopeful signs with the destruction of the rebel battleship Espana, by a mine off the harbour, and the besieging of the Italians in Bermeo by several Basque battalions. Meanwhile, Leah continued discissions on the evacuation of Basque children, believing that there would only be some 250 to 500 children to evacuate, Leah was surprised to find that the true figure was around four thousand. Needless to say the British Government continued to prove unhelpful.

“The Basques had no sympathy either from the Home Office or the Foreign Office. Both regarded the whole thing as a nuisance and myself as an officious busy-body. They changed the ages; they changed the policy of receiving the children in family groups; and they demanded that the London Committee should guarantee ten shillings per week per head for each child—this at a time when they expected the children of their own unemployed to survive on five bob a week.”

In addition to the evacuation of children, old people and invalids were evacuated as refuge and transport became available. Before Santander and Bilbao fell more than 100,000 non-combatants left for Russia, England, France, Belgium and Catalonia. Evacuation was managed by careful publicity, by absolute fairness in the choice of evacuados and in the order of their going; and by the creation of confidence in the people responsible. Radio and Press were requisitioned for publicity purposes; the President, his Ministers, well-loved priests and public personalities all made broadcasts. To establish a feeling of fairness, invitations were issued to all those persons who wished to leave Bilbao and who had sufficient means to support themselves or friends to whom they could go. They left on the Habana and the Goizeka-Izarra. This gave time to make preparations abroad for the reception of refugees without means, the first of whom (1,000 women and 2,500 children) left for France on 6 May . Whenever a group of needy refugees was ready, it was given precedence over wealthier persons, or went with them. When the French Government sent three boats unexpectedly, they were filled with 2,000 old people and children, half of whom could pay their way and maintain themselves; the other half poor people going to colonies in the French Basque Provinces arranged by the Basque Government.

On May 16 the Habana and the Goizeka-Izarro returned from their first journey and took off 4,000 refugees, mainly people who could pay their fares and maintain themselves. But for the vacillations of the British Government, the children should have been on that voyage. The people understood that, while wealth could claim no privileges, there was no arbitrary holding back of people willing to make their own arrangements. The evacuados were allocated from among the political parties in strict proportion to their electoral representation in the Basque Government. The British Government also insisted ‘that persons, supporting General Franco should be included in the party if they desired evacuation.’ The establishment of confidence was as important as the establishment of fair play. Whenever possible, whole families, mothers, their children and elderly relatives, were evacuated together. France accepted refugee groups of this kind; and those sent to Eastern Spain and the Basque colonies in France were also family groups. Many thousands of children were evacuated, without their families, to England, Belgium and Russia. Confidence was established in the hearts of mothers of such children when many teachers volunteered to accompany them—mothers were willing to put their children in charge of teachers they knew. Although nominally in charge only of the evacuation to England, Leah Manning was present at all embarkations and received much publicity in the city. She went with the President to mass meetings, did interviews with press and leaders of political, religious and social groups, and at the Department of Assistencia Social for talks with parents, teachers and auxiliars. In a few weeks she was recognised on the streets and the mothers of Bilbao began to feel their children were in charge of someone in whom they could place their trust. Leah Manning became afraid that the carefully built confidence would evaporate as it became known that there was a growing reluctance on the part of the British Government to accept any of the plans so carefully detailed by the Basques. In particular , the refusal to accept any child under eight or over fourteen undermined ideas about families staying together. Leah Manning began to send out imploring telegrams—to the Archbishop of Canterbury, to the Catholic Archbishop, to Lloyd George, to Citrine. The Foreign Office apparently left it to Mr Stevenson , who was adamant that he could not advise His Majesty’s Government to accept 4,000 children of all ages. By Leah’s account , while Stevenson was in St Jean, to celebrate the Coronation. the Basque pro- consul Sefior Oganguerren sent the telegram. It went off that same night and the reply, in confirmation. From then on things began to move very quickly. Two paediatric doctors, Dr Richard Hill and Dr Audrey Russell, were flown out by the Committee to help in the final stages of embarkation and the journey by sea.

The British government, however, refused any financial responsibility for the children and made it a condition that no public money was to be used to support them: they were to be supported entirely by volunteers and voluntary funds. While the Germans and Italians were busy Not intervening by bombing Guernica, the British government argued that supporting the child refugees would violate the Non-Intervention Agreement. It demanded that the newly-formed Basque Children's Committee guarantee 10/- per week (equivalent to £30+ today) for the care and education of each child.

The SS Habana was made ready on 21 May. The ship, built to carry around 800 passengers, carried more than 3860 children, 95 teachers (maestras), 120 helpers (asistentas), 15 Catholic priests and 2 British doctors. The children were crammed into the boat, and slept where they could, even in the lifeboats.on the night of departure , the quay was a thick, black mass of parents, defying bombs as the children, some happy and excited, some in tears, were taken aboard in orderly companies. The ship sailed into International Waters, where she was met by two ships of the Royal Navy to protect her voyage. Each child had a cardboard hexagonal disk with an identification number and the words 'Expedición a Inglaterra' printed on it.The journey was extremely rough in the Bay of Biscay and most of the children (and staff) were seasick.

While Leah Manning was aiding relief efforts in Bilbao, she received powerful support at home in the somewhat unlikely form of Scottish Unionist noblewomen and MP. Katharine Marjory Stewart-Murray, Duchess of Atholl. The Duchess was active in Scottish social services and local government and in 1912 served on the hugely influential "Highlands and Islands Medical Service Committee" widely credited with creating the forerunner of the National Health Service. Despite her opposition to women gaining the right to vote in parliamentary elections, she went on to be the Scottish Unionist MP for Kinross and West Perthshire from 1923 to 1938 the first woman elected to represent a Scottish seat at Westminster , and served as Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Education from 1924 to 1929. in April 1937 she, Eleanor Rathbone, and Ellen Wilkinson went to Spain to observe the effects of the Spanish Civil War first hand They witnessed the effects of German bombing in Valencia, Barcelona and Madrid , visited prisoners of war held by the Republicans and considered the impact of the conflict on women and children, in particular. Her support for the Republican side in the conflict led to her being nicknamed by some the Red Duchess. She became active in the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief, a cross-party group coordinating aid to Spain and instrumental in persuading the British government to accept child refugees fleeing the combat. Although perhaps not as recognized as Leah Manning, the Duchess provided vital support in London lobbying British officials to do something about the Basque evacuation.

Postcard of the Casino and the funicular up to Artxanda

While the civilian evacuations progressed by 11 June 1937, thanks to Goicoechea’s betrayal, the Iron Ring was breached by a rebel infantry assault supported by heavy air and artillery bombardment from 150 guns and 70 bombers, being completely overwhelmed in two days. On 12 June, the Spanish Republican Army launched a diversionary attack against Huesca to stop the rebel offensive, but the rebel troops continued their advance. All that the Basques could do was buy some more time to evacuate their battalions from Bilbao. On the morning of 16 June, the first Basque Division occupied the heights east of the city, over a 2km front between Artxanda and Berriz. The fighting centered around the Artxanda Casino and its surrounding park.

The casino at Artxanda

Built in 1915, the Casino, was not only a gaming house, but apparently a centre for a wide circle of cultural and sporting activities for the population of Bilbao. It was reached by a Funicular from the town centre and commanded spectacular views over the city. For this reason it was of considerable strategic significance. Once that defence line was breached , the attackers could simply proceed downhill and into the centre of Bilbao. Rebel artillery and aircraft bombarded the defence line, with some 30,000 shells, while the rebel aviation and their German allies bombed and strafed the city. Nevertheless, the gudaris continued to repel the attacks..

Recreation of trench positions around Artxanda

On 17 June, the defenders were forced to evacuate their positions at the Casino but the Basque Government ordered them to hold on another day, to enable evacuation to be completed. Although the promised air cover never arrived, the gudari recovered the Casino building. In bitter fighting, they survived three fierce attacks during the day , with the Casino changing hands several times , until at nightfall with most of the defenders dead the rebels finally took the casino. Those defenders who could not escape to the city were massacred up in the hills. Prominent in the defence of Bilbao was a French national Lt. Colonel Joseph Putz, a veteran of the French Army in WW1 and former trade union activist and public official who had commanded the XIV International Brigade , participating in the battles of Lopera, La Coruna Road and the Jarama. Based on his successful record , he had been appointed to command the 1st Basque Division. Thanks to the time bought at very high cost by the heroic Basque defenders up at Artxanda, the remnants of the Basque army was able to stage an orderly withdrawal from the city. On 19 June the rebels occupied Bilbao.

Santander

After the fall of Bilbao the rebels turned their attention to Cantabria. In July 1937, the government ordered an offensive on Brunete, as a manoeuvre to relieve the siege of Madrid and block the Francoists' route to the North. The Battle of Brunete ended towards the end of July, and Franco concentrated his troops in the area to attempt an advance towards the North. On 6 August, the central government created the Army of the North, headed by General Mariano Gamir Ulibarri, composed of representatives of the governments of Asturias, the Basque Country and Cantabria, in order to coordinate the defence . The inhabitants of Santander, already exhausted by the persistent food shortage and the continuous air raids of the rebel air force, began a feverish construction of barricades. At the same time, the evacuation of numerous Basque refugees towards France began.

The defence of Cantabria counted on 80,000 troops incorporated into four armies: the XIV of the Euzko Gudarostea, the XV composed mainly of Cantabrian troops, and the XVI and XVII composed mainly of Asturians.. The Republicans had also 44 aircraft (mostly slow and old, except 18 Soviet-built fighters). Ranged against them the Rebel Army of the North had 90,000 men (of which, 25,000 Italian), led by General Fidel Dávila Arrondo. The Italian force, led by General Bastico, comprised Bergonzoli's Littorio Division, Frusci's Black Flames Division and Francischi's 23 March Division. The Francoists also had six Brigades of Navarre led by Colonel Solchaga, two Castilian brigades led by General Ferrer, and one mixed Hispano-Italian division, the Black Arrows, led by Colonel Piazzioni. They had vastly superior in air power with 220 modern aircraft (70 of the Condor Legion, 80 of the Aviazione Legionaria and 70 Spanish), including many German Bf 109 fighters.

The battlefield was located on the mountainous terrain of the Cantabrian Mountains, whose highest (and most advantageous) peaks were in Republican hands. The first line was located in the southern area between Reinosa and Puerto del Escudo, with a Republican trench area between Santullano, Soncillo Aguilar de Campoo and Soncillo. This proved to be a mistake due to the difficulty in supplying the troops and the difficult position. The morale and physical condition of the attackers was superior to that of the Republicans. Many Basque units did not want to fight outside their own territory, and relations between the Asturian, Basque and Cantrabrian battalions were difficult. Rumours that the Basques were negotiating the surrender with the Italians made the relations between the different brigades even more tense.

On 14 August, the Francoist operations began, with the first target being the Constructora Naval weapons factory in Reinosa and the railway junction of Mataporquera. The aim of this operation was to cut off the government's main communication artery. On the first day of combat, the Navarra Brigade broke the Republican line on the southern front, which had already been severely damaged by air attacks. On the 15th, the Nationalists advanced to Peña Rubia, Salcedillo, Matalejos and Reinosilla, encountering strong resistance in Portillo de Suano. General Gamir Ulibarri planned a desperate line of defence in the northern area between Peña Astía - Peña Rubia - Peña Labra. Six thousand Republicans died in the defence of Reinosa. The Fourth Navarra Brigade managed to break the resistance of Portillo de Suano, working to keep the factory complex intact, thwarting the workers' intention to destroy it so as not to let it fall into Francoist hands, and entered Reinosa at dusk. Italian forces advanced in parallel along the Corconte - Reinosa road, before the Republican forces withdrew to Lanchares and then to San Miguel de Aguayo.

On 17 August, the Italians of the 23 March Division broke through the Republican defences to conquer Puerto del Escudo. With this "pincer" attack, the Francoist forces managed to strangle the Republican defences in the Alto Ebro dealing a tremendous blow to the morale of the Republican troops. From there the offensive continued in two directions, towards the four valleys (Valle Cabuerniga, Valle Besaya, Valle Pas and Valle Carriedo) and the town of Torrelavega, to cut off the withdrawal of forces towards Asturias. The Italian Blackshirts opened the front to the west along the coast and reached the Agüera River and the Asón River. The entire defensive system created by General Gamir Ulibarri for the Republicans was destroyed and no longer able to prevent the rapid advance of the enemy. Gamir Ulibarri decided to send all the troops from a reserve to the front line and urged the XIV Army Corps to urgently send two Basque brigades from Carranza to Ramales de la Victoria. Francoist troops from Navarre occupied Santiurde, while the Italians reached San Pedro del Romeral and San Miguel de Luena.

The rapid Francoist advances forced Gamir Ulibarri to organize the withdrawal plan for the defence of Santander. On the 20 August , the XVII Army Corps positioned a brigade in Torrelavega and the Basque Divisions were deployed in Puente Viesgo, to defend communications with Asturias. Italian forces continued their advance towards Villacarriedo and the Navarre brigades continued to Torrelavega and Cabezón de la Sal. On 22 August , the Francoist having conquered Selaya, Villacarriedo, Ontaneda and Las Fraguas, were a few kilometers from Torrelavega and Puente Viesgo. Given the critical situation the Republican government decided to retreat to Santander and resist for 72 hours, in order to wait a proposed counter-offensive on the Aragonese front.

On 24 August given the numerical inferiority and the terrified morale of the troops, General Gamir Ulibarri ordered the evacuation of Santander to Asturias.. The Francoists captured Torrelavega in the evening and cut off land communications with Asturias..The following day , General Gamir Ulibarri, along with Russian General Vladimir Gorev and several politicians, including Basque President José Antonio Aguirre, left Santander aboard a submarine, heading for Gijón . The exodus of politicians and officers left the population without a leader and entire brigades without command. The Republican forces remaining in Santander surrendered.

At midday on 26 August, soldiers from the Fourth Navarre Brigade and the Italian Littorio Division entered Santander. Those closest to the Republican government spent a tense forty-eight hours waiting to find a place on one of the ships that were evacuating the city to France. Those who could not escape were subjected to summary trials and executions. 17,000 prisoners were captured, many of whom were shot immediately. On 31 August ,the remnants of the Republican army retreating towards Asturias burned Potes. In the days that followed, the Nationalists occupied the Cantabrian territory, completing the military operations on 1 September with the occupation of Unquera, at the mouth of the Deva River.

At Santona, the president of the Biscay Regional Council of the PNV, negotiated a surrender agreement with the Italian army command. The PNV offered to surrender the Basque army in exchange of its prisoners being treated as prisoners-of-war under Italian command and PNV members being allowed to go to exile on British ships.. When news of the agreement arrived to his headquarters, Franco cancelled the agreement and ordered the immediate jailing of the 22,000 captured soldiers in Santoña's El Dueso Prison. Three months later, around half of them had been freed, and the other half remained in prison, and 510 were sentenced to death.

Santander's fall, coupled with the capture of Bilbao, tore an irreparable gap in the Republic's northern front, and marked another crippling blow to the Republic's sagging strength and turning the war to Franco's favour. Of twelve Basque brigades there remained at the end only eight battered battalions. The Republican Army of Santander of twelve brigades was reduced to six battalions. The Asturians committed 27 battalions and escaped with only fourteen. Sixty thousand Republican soldiers were wiped off the map, with corresponding losses in materiel. The War in the North was all but over

Aftermath

After the fall of Bilbao and Franco's capture of the rest of northern Spain in the summer of 1937, the process of repatriating the evacuated Basque children began. By the start of World War II in 1939 most of the children had left for Spain. For some this was a terrible ordeal, they had forgotten their Spanish, or worse - their parents. The 400 or so young people who remained in Britain either chose to stay (if they were over 16, they were given the choice), or had to stay because their parents were either dead, imprisoned or their whereabouts was unknown. By 1945, there were still over 250 Basque refugees in Britain and many of these settled permanently, remaining in Britain for the rest of their lives. Lt Colonel Joseph Putz , who had led the defence of Bilbao went on killing Fascists. With the Republican government defeated, he returned to French Algeria and when the Germans invaded France , he joined the Free French Forces. He returned with General le Clerc’s Army to liberate France , for a while serving with the Neuve, a company of exiled Spanish Republicans fighting with the allies. Still fighting Fascists, he was killed in February 1945, while helping to liberate Alsace from the Nazis.

Statue commemorating George Steer in Gernika

George Steer was fired by the Times for his anti-Fascist stance, he returned to South Africa and then covered the 1940 Winter War in Finland for the Daily Telegraph, He joined the British Army in June 1940 and served against the Italians in Abyssinia. He was killed in a traffic accident while serving in Burma in 1944. There is a fine bust of him in Guernica and a street in Bilbao named in his honour . Leah Manning is remembered for her work with Basque children, by the Plaza Mrs Leah Manning in Bilbao . In 1997, on the 60th anniversary of the bombing of Guernica, the German President Roman Herzog wrote to the survivors apologizing on behalf of the German people for Germany’s role in the Spanish Civil War.

Of the ships involved off the coast of Spain, HMS Blanche was sunk by a mine in November 1939, becoming the first British destroyer lost to enemy action in World War II. HMS Brazen participated in the Norwegian Campaign in April–May 1940 and was sunk in late July 1940 by German aircraft while escorting convoys in the English channel .HMS Fearless later formed part of Force H where she participated in the bombardment of Genoa. She was torpedoed by an Italian bomber while escorting Malta convoys and had to be scuttled on 23 July 1941. In May 1941. On 24 May 1941, early in the Battle of the Denmark Strait, HMS Hood was struck by several German shells, exploded, and sank with the loss of all but 3 of her crew of 1,418.

On the other side, Genera Mario Roatta , the Italian General who had negotiated the surrender of the Basques at Santona and then set back and watched the Spanish renege on it found his Spanish connections useful. While the British blocked his extradition to Yugoslavia to face war crimes trials, he walked out of a Rome hospital in 1945, from where he made it to Spain where he lived under Franco’s protection until 1966. An Italian court convicted him in absentia ad sentenced him to Life imprisonment , a sentence overturned on appeal in 1945.

Claude Bowers description of San Sebastian and the War in the North from

My mission to Spain; watching the rehearsal for World War II

Claude G Bowers, Simon & Schuster , New York 1954

The stories of the Tyneside Ships which ran the rebel blockade to bring humanitarian aid to Bilbao are toldin a series of articles on the blog of Tyne and Wear Museums

Danger and adventure for Tyne and Wear ship's crews in the Spanish Civil War

Newcastle food ships rescue Basque refugees in the Spanish Civil War

The role of the Royal Navy in the Spanish Civil War is covered in an interesting published thesis

The Royal Navy & the siege of Bilbao

James Cable, Cambridge University Press 1979 (Available to borrow from Internet archive

Dame Leah Manning's experiences in Spain are described in her autobiography

A Life For Education, Victor Gollancz - London 1970