A walking tour of the stolpersteine around from piazza Cadorna to Sant'Ambrogio

This is a walking tour of the stolpersteine of Milan in the area around Cadorna, Corso Magenta and Sant’ Ambrogio , The tour starts at Piazza Cadorna at the station and follows a more or less circular route : The whole route takes about four hours. The monument for Luigi Bassi is quite some way from the others , so if you are short on time you might want to omit that one. It is also close to the metro station at Tre Torri if you want to save some walking.

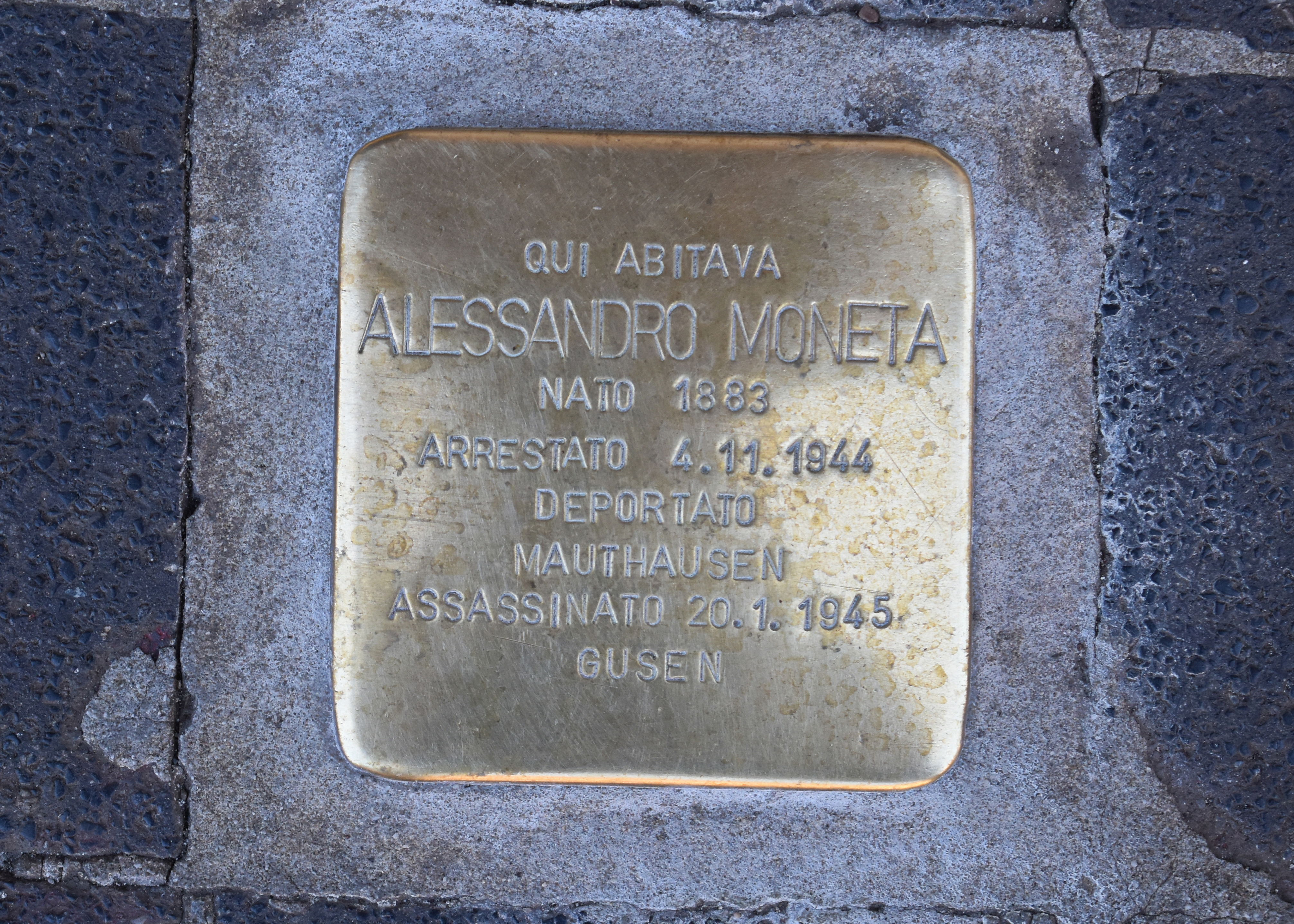

Coming out of the metro in piazza Cadorna, you need to exit the piazza in front of Cadorna Station, turn to the right and across the road is a row of shops and offices. The large commercial looking building we are looking for is currently the Croatia Consulate, at Piazza Cadorna 15 so it is fairly difficult to miss. Here we come to our first stone, commemorating Alfredo Moneta

Alfredo came from a family of Milanese industrialists. His father’s business Giuseppe Moneta snc was based at in Musocco on the outer edges of Milan, the firm produced enamel ware and metal goods, during the First World War it was famous for producing thousands of helmets for the Italian Army. A decent and cultivated individual, Alessandro went to work for the family business. After the Racial Laws he started employing Jewish workers, then progressed to hiding them both in the factory and around the Moneta country villa. Alessandro was arrested for the offence of giving aid and succor to Jews , taken to San Vittore , then Bolzano and Mauthausen. He died at the notorious sub-camp of Gusen on 20 January 1945.

The next stone is about twenty minutes to half an hour walk all the way via Vincenzo Monti, Via Monti, starts as a well shaded residential street with some nice-looking restaurants and substantial and wealthy looking apartment blocks As you keep going up the road, the residential area gives way to old barrack buildings one for the Carabinieri and one for the Alpini. Keep going straight and after the Alpini barracks cross the large junction where you pass a monument to the war dead of the Alpini. This is still via Monti but considerably different from the lower part. There is a good reason for that. Before 1931, when the new Central Station was opened ( including its notorious Binario 21), this was the Stazione Smistamento Sempione. When Milan’s whole railway network was rerouted following the closure of the Old Central Station , the Sempione shunting station was closed and redeveloped as the Parco Pallavicino , and via Monti continued across it . So the buildings after the park are considerably newer than those further down the road, which is why the stone for Luigi Bassi at via Vincenzo Monte 92 is outside a much newer looking apartment block.

Luigi Bassi was born in 1895 at Budrio (BO) he married Luisa Federici, with whom he had two children. Luigi worked for twenty years at GI-ER-CI, an automotive parts supplier , until becoming a director of Edera, another auto parts supplier in Corso Sempione 51. This would have been a fairly quick trip from his home, since via Monti is on a parallel with Corso Sempione. Luigi was a member of the Partito Socialista and did not hide his anti-fascism , He was arrested on 21 March 1944 and taken to the German wing of San Vittore, then transferred in April to Campo di Fossoli, from where he was deported on 21 June1944 on transport n.53 to Mauthausen. On 13 December 1944 he was transferred to the sub- camp of Gusen, where he died on 28 January 1945.

The via Monti terminates in piazza 6 Febbraio right opposite the new City Life quarter of Milan directly in front is the Palazzo Scintille once part of the Fiera Camponiara , the old site of Milan’s Trade Fairs .

This whole area has now been redeveloped and the only remnants of the old Fiera of the Inter War Years are the Palazzo Scintille and the two liberty style buildings which once formed the entrance to the viale Industria which ran directly across the fair site. The Palazzo was inaugurated in 1923 for the Salon dell ‘Automobile and subsequently became the Palazzo de Sport and even later in 1946 hosted a season of La Scala which had been bombed out of its home during the war.

Citylife now houses a shopping centre and three modern office towers, You might want to linger a while in this area. If you have time . Returning down the via Monti, we go back past the barracks . This time at the Largo Quinto Alpini .we turn right and head into via Mario Pagano.

We pass, what is left of another barracks and come to another long road of liberty style mansion blocks . At number 36 via Mario Pagano , we find the sone commemorating Edgardo Finzi (there is also another different Edgardo Finzi commemorated at via Fillipo Lippi)

Edgardo was born in Ferrara in 1889, , he had fought for Italy in the First World War and had been decorated for his services. After the war he married Giulia Robiati, and they had two children Carlo and Fausta. Edgardo, worked as a bank employee and left his position voluntarily in 1939, by when the racial laws had become too suffocating. He started his own small business making paints in via Compagnoni. His daughter Fausta worked with him on the bookkeeping.

As the persecution of Italian Jews intensified, Edgardo’s brother Arrigo, pressed him to flee to Switzerland, but he was attached to his family , home and work and fatally believed that Italy would not see the worst of the persecution. In 1938 , as a mixed family the family had requested exemption from Italy’s Racial laws , since Edgardo’s wife and children were Catholics. They were granted the discrimination anyway, but not Edgardo since he had never been a member of the Partito Nazionale Fascista. He was finally granted in 1941, but as far as the Germans were concerned the Italian certificates were not worth the paper they were printed on.

On 22 April 1944, probably as result of a tip-off , two men turned up at his workplace in via Compagnoni and took him for questioning, One of the Germans was identified by Fausta as the notorious Otto Koch. Koch was 36-year-old former police officer from Halle , Germany who had later worked for the Judenreferat when the Germans occupied Vienna. Having arrived in Milan, Koch established his brutal credentials with a raid on the synagogue in Via Guastalla, which left one man dad and fifteen detained . he was known as Judenkoch , literally the cooker of Jews. In Milan Koch headed Referat IV/ b of the SD responsible for Jewish affairs. As a result of the double reporting structure of the SS, Koch was subordinate to Sturmbannfuhrer Friedrich Bossheimer, a lawyer who headed the Judenreferat for Italy in Verona and to SS Hauptsturmführer Theodore Saevecke who headed the SD if -Milan. It is estimate that the odious Koch personally arrested some 10 to 20 Milanese Jews, the rest were delivered to him by Italian Fascist groups or other German units. Often he worked in tandem with a Jewish informer Mauro Graziado Grini , who went by the alias Dott. Manzoni. Grini was a Jew from Trieste who had been disowned by his family for his womanising ad gambling. his family ended up in the Trieste Concentration camp of Risera Saba. Grini claimed that he worked for the SD to protect his family. He was however paid a stipend of around 7,000 lire a month and allowed by the Germans to carry a gun, Fausta Finzi was sure of the identity of Koch, maybe the other man was his Italian collaborator Grini.

When the two SD men arrived, Fausta, did not want to leave her father and accompanied him, but they ended up in San Vittore, On 27 April, they were taken to Binario 21 and from there to Fossoli. As the allies advanced up the Italian peninsula the camp at Fossoli was abandoned and they were transferred to Verona. On 2 August 1944 Edgardo Finzi was put on transport 72 and deported to Auschwitz, he did not survive the “selection” procedure and was murdered on the day of his arrival 6 August 1944.

Fausta was deported to the female camp at Ravensbrück, when the Germans abandoned the camp she was forced to join one of the death marches to the west , the column was liberated by the Americans and the guards fled, unfortunately they were in the zone which had been promised to the Soviets , and after witnessing the indiscriminate sexual violence perpetrated by the Soviets in their occupation zone, she was forced to flee to the west . She managed to survive and continued to bear witness to the Shoah until her death in 2013.Koch and Grini disappeared from the face of the earth, Grini was tried by the Italians in absentia in 1947, but possibly he was already dead at the time. It took until 1967 for the Germans to bring Bossheimer to trail for his crimes in Italy . He was finally sentenced to life imprisonment but died before serving single day of prison time.

Next on via Mario Pagano at number 42 was the home of Gian Natale Suglia Passeri

Gian Natale Suglia Passeri was born on 15 December 1923 in Milan, the son of Michele Suglia Passeri and Bianca Bozzolo. Michele was a former Captain in the medical corps who had seen service at Caporetto After the war he had opened a private clinic in Milan for treating Mental illness. He had again enrolled in the Army medical corps during the Ethiopian invasion. Gian Natale attended the prestigious Collegio San. Carlo in corso Magenta and completed his maturity exams at the Collegio Rotondi in Gorla Minore ready to enrol in an engineering degree. After the 8 September Gian Natale refused join the forces of the R S.I. and tried, without success to get South to Bari to join the Italian army. Unable to do that he joined the Milan network of the clandestine Partito liberale under Luciano Elmo, helping with propaganda, acquiring rations for the partisan in the mountains and getting false papers . All very dangerous tasks. He was arrested on 31 July 1944 at around 13.00 when fascist Militia entered the studio of avvocato Elmo, in viale Regina Margherita 38, which was the operations centre for the military wing of the Partito liberale. This was the first in a chain of arrests which over the next few days, eviscerated the liberals, capturing Guglielmo Barbò, Raffaele Gilardino, Antonio De Finetti, Carlo Vezzani, Luigi Pyrazole and may others. Gian Natale was imprisoned at San Vittore, then transferred to Bolzano and on 5 September to Flossenburg, he died at the subcamp of Hersbruck on 2 December1944.

About 100 metres further down via Pagano, we come to another prosperous looking building for which the stone outside number 50 commemorates Anna Rabinoff Schweinöster

Anna was born Simferopoli (Crimea)in April1881, from a landowning family , she became one of the first women in Russia to graduate in orthodontics. She was a free spirit, and did not wish to practice as a dentist, so she moved to Milan to study singing instead. She married Georg Schweinöster, a Bavarian who had an import /export business in Luino on Lake Maggiore. The family moved to Zurich before the First World War where a son Giorgio was born in 1917, After the war they returned to Luino, In 1927 Anna was widowed , and devoted herself to Giorgio0s education . , he graduated from Università Bocconi. Following the Racial laws , Anna and Giorgio decided to leave Italy and transferred to Bombay, where Giorgio following his father’s footsteps had got a position as a freight forwarder. Anna did not settle to life in India and returned to Italy. Anna was still recorded in the 1938 census as being Jewish. On 17 July 1938 the then Central Demographic Office of the Ministry of the Interior changed its name and responsibilities to become the Direzione generale per la demografia e la razza (Directorate General for Demography and Race) (also known by the acronym Demorazza). On August 22, 1938, a census of Jews was carried out, in order to count and file the number and identity of Jews residing in Italy, as a prerequisite for the enactment of the racial laws. The Fascists wanted to use the census data to demonstrate the presence of a significant number of Jews in Italy and create a consensus around the introduction of discriminatory rules by talking up a danger that nobody had previously felt. In fact Italian Jews were some 47,000, equal to less than 0.1% of the Italian population. Unfortunately nobody had the good sense to destroy the census data before the Germans arrived, so they were presented with a ready made list to find and deport Italian Jews.

Anna was arrested on 13 October 1943 and incarcerated in the Jewish wing of San Vittore. On 6 December 1943 she was deported to Auschwitz and murdered on arrival.

From via Mario Pagano we head back Conciliazione . on the corner there is not a stolperstein, ( those are reserved for the deported) but a memorial to Eugenio Curiel a brave partisan who bled to death at the spot , having been ambushed by Fascist gunmen. From Conciliazione, we turn into Va Settembre and find the entrance to via Rovani at number 7 is yhe stone commemorating Giulio Ravenna.

Even converting to Catholicism did not save Giulio Ravenna. He was born in the city of his name in 1873, to Isacco and Emma Levi. He married Maria Ferrari, the couple had two children , Giano and Diego. They moved to Milan in man, where Giulio practised as a Bankruptcy Administrator In the early 1930s both Giulio and his younger brother Rino Lazzaro Ravenna got to know Fra Giuseppe (Leopoldo Riboldi 1885 – 1966), a Dominican friar at the nearby church of Santa Maria delle Grazie and converted to Catholicism. Nevertheless under the Racial Laws they were recorded as being Jewish in the census.

After 8 September the whole family decided to see asylum in Switzerland , where Diego had already managed to get ecsape with his family The Ravenna brothers were cousins of Alberto Segre and his daughter Liliana and attempted to escape with them through the Swiss border at Saltrio. They were turned back at the Swiss border and forced to return to Selvetta di Viggiù (VA)where on 8 December 1943 they were arrested and imprisoned at Varese. Giulio Ravenna was transferred to Fossoli, where he died on 18 February 1944.his brother Rino Lazzaro Ravenna was transferred to San Vittore where he took his own life on 29 January 1944.

At the end of via Rovani, you can see the church of Santa maria delle Grazie, where the Ravenna brothers had taken catholic instruction, Passing by the church and the Cenacolo of Leonardo da Vinci,( even if you would like to call in you need a timed ticket) , we emerge on Corso Magenta.

About a hundred metres down Corson Magenta on the right hand side of the road, at Corso magenta 55 we come to the stones commemorating the Segre family.

Giuseppe Segre was born in Milan in March 1873. In 1897 together with his friends Schieppati and Dacono he founded the textile business Segre & Schieppati . After the First World War, Giuseppe became the sole owner and the business expanded especially in the shoe and leather industries. He married Olga Lovvy from Turin in 1897, and they had two sons Alberto and Amadeo. As well as being successful in the textile business, Giuseppe Segre contributed notably to charity, being one of the funders of the humanitarian Croce Verde of Milan, becoming a Cavaliere della corona d’Italia for his services to charity. After the Racial laws, the family business was confiscated by the Fascists. Giuseppe and Olga went to hideaway in the hills at Inverigo, near Como. As usual somebody betrayed them and they were detained on 18 May 1944, and deported to Fossoli, They were murdered at Auschwitz on 30 June 1944.

Giuseppe’s son Alberto was born in Milan on 12 December 1899. He studied at Milan’s Liceo Manzoni and was drafted as one of the ragazze del 99, the draft year that helped to save Italy after the military collapse at Caporetto in 1917. Alberto rose to be a second lieutenant in the Artillery. After the war he graduated in economy and commerce and joined the family business, he looked after the bookkeeping while his more outgoing brother Amadeo looked after the commercial side, Alberto married Lucia Foligno in 1929, their daughter Liliana was born a year later. Tragically Luciana died at 25 and Alberto was left to dedicate himself to bringing up his daughter. He did not think of leaving Italy or his ageing parents. Alberto arranged for Liliana to be hidden by family friends in Castellanza, a town some 30km north of Milan, near Varese where she stayed for a month or so. Since she was Jewish and her father had arranged false papers for her, the family were risking their own lives if caught.

Meanwhile, Alberto thought he had obtained valid exit papers for his aged parent to leave Italy ( unfortunately that transpired to be incorrect) , so he set off to retrieve Liliana. They had been put in contact with some smugglers on the Italian side of the border, who as well as smuggling cigarettes and other contraband from Switzerland , also smuggled people across the border. They did not do so out of the kindness of their hearts and Alberto had to pay a high price for the service. Having collected Liliana , Alberto met the smugglers on the Italian side of the border at Viggiu and the moved upwards in the hills towards Saltrio , close to the border. They could not just walk along the road to the frontier post and had to follow the smuggler’s routes. The smugglers took them to a mountain shack for the night, where they were surprised to find two elderly cousins also waiting to be taken over. The smugglers took all four up to the ridge and pointed downwards towards Switzerland and left them to it . Alberto was forced to carry the two elderly relatives down a precipitous slop towards Switzerland and the clear a passage through the border fence .

There was a light rain drizzling and around dawn on 7 December 1943, they crossed into what should have been safety by cutting through the wire on the border fence . They encountered two Swiss soldiers, at first fearing them to be German because of the similar unform and were taken to the Swiss frontier post at Arzo. Their timing was very unfortunate Since 8 September , the Swiss had gone through periods of opening and closing the border. From 8 September to13th it had been open as a huge influx of Italian soldiers, allied PWs ad refugees crossed over into Italy On 13 September the border was closed . After pressure from the Canton of Ticino, the border reopened again on 24 September ,with some clear rules in place on the granting of asylum. In accordance with the laws of war , uniformed Italian soldiers and PWs were allowed in, also admitted were political refugees and specifically Jews facing persecution. Decisions on asylum were to be made locally but the border guards or the cantonal police.

On 30 November , the Ministry of the Interior of the RSI issued an order for the arrest of all Jews in Italian territory and fearful of another exodus into their territory, the Swiss border was closed again. It appears that the last successful acceptances for asylum at Arzo were granted on 2December. By the time the Segres got to the border, it was being manned by a mainly Swiss German regiment brought down from Fribourg. After getting through the border fence the Segres were detained by the Swiss German soldiers and taken down to Arzo, there instead of being handed over to the border guards they were held at the Army’s -barracks at the local school. It then appears that two Army officers then took the decision to hand them back to the Italians.

Liliana recalls them being marched there past Swiss villagers who refused to acknowledge them or looked away. At the frontier post, a belligerent Swiss German officer accused them of being liars and said that there was no persecution of the Jews in Italy . Liliana implored the officer to let them stay, Alberto offered to go back if she was allowed to stay , but he refused to even countenance that. At around 1630, the Swiss handed the tragic little party over to the Italian frontier guards. They had spent less than a day in the supposedly “safe haven” of Switzerland.

Back in Italy, the family were separated, and Liliana was sent to the female wings of first Varese and then Como prisons. She was reunited with her father in the Jewish wing at San Vittore where the German guards kept Jewish families together. Liliana recalls that the morning they marched out of the of Jewish wing to be deported, the only humanity was shown by the Italian prisoners in the ordinary criminal wings of San Vittorio. They might have been murderers, robbers, black marketeers or con men, but as the Jewish prisoners were marched out, they shouted blessings and encouragements and even threw food or other small gifts to them. Liliana puts it that ;”They would be the last men we met”- which is probably true since after that they were in the SS run camp system far from humanity or anybody who might reasonably call themselves a man. They were kicked, punched and beaten as they were forced onto trucks at San Vittore, then driven at dawn through the deserted streets of Milan, on the way they passed by their house at corso Magenta 33, Alberto would never see it again.

At Binario 21 of, they were again kicked, punched and abused as they were taken into the netherworld of the underground platforms, which the Germans used to keep their nefarious activities hide from Italian eyes. Then they were put on a cattle truck on the train which left Binario 21 for Auschwitz on 30 January 1944. Albert died at Auschwitz on 27 April 1944.

Amadeo survived the war and took over the family business. Liliana survived Auschwitz and was appointed an Italian Senator for Life and sort of conscience keeper for a nation rather keen not to come to terms with its dark past. It took many years for Liliana to speak about what happened but then she began to talk and give interviews as to what happened. The Swiss reopened the border some days after the Segre family had been rejected and from March 1944 onwards no more Jews were returned to Italian territory.

About fifty metres past the Segre’s house, you turn into Via Aristide de Togni and the commemoration for the Reinach family,

Ernest Reinach was born in Turin in 1853, his family had emigrated to Italy from Prussia, In 1882, the young Ernesto funded a company in Milan, Ernesto Reinach Lubrificanti which produced industrial lubricants. As the Italian automobile industry developed, the company branched out into automotive lubricants, especially with the name “Oleoblitz”. It soon became famous, the company-s publicity began to appear on Touring Club of Italy maps, it was the official lubricant for the legendary Marque of Isotta Fraschini . Oleoblitz became associated with the great early years of Italian motorsport, with Alfa Romeo, with Motorcycle raids and the Targa Florio. They were in on the early days of Italian Aviation, sponsoring the first meeting of Italian Aviators at the newly opened Taliedo Aerodrome ( just outside Milan) in 1911, The firm exported to the Italian Empire in Eritrea and Libya. Reinach-s daughter married at noted Turin lawyer Ugo de Benedetti who moved to Milan, developing a name as lawyer to some of the best known Italian commercial and industrial groups. He had two sons, Giancarlo and Piero. By autumn of 1943, the family must have been feeling unsafe in Milan. The Reinach family had a country villa at Lanzo D’Intelvi in the hills above Lake Como, from where you could literally walk into Switzerland from the back garden.

Other members of the family had already safely crossed into Switzerland using that route. They were helped by the custodian of the Villa, Giuseppe Grandi. While the Fascist gangs of Milan collaborated with the Nazi occupiers and did substantial amounts of their dirty work, ordinary Italians like Grandi shine out as a beacon of hope. In the end he paid with his life. Grandi was denounced for assisting Jews , arrested by the Germans, and died at Buchenwald.

Ernesto Reinach and family packed up the big old Isotta Fraschini and set off for Lanzo. They made it as far as Torrigia, a small town on the shores of Lake Como from where the road goes up into the hills towards Lanzo. They were literally less than hour from freedom when they were arrested by a German patrol. At the beginning of November 1943, Ernesto Reinach, Maria, Ugo de Benedetti and Piero de Benedetti were arrested at Torrigia. They were taken to San Vittore Prison. On 6 December 1943, they were taken to Milan Central Station, walked through the doors and into the underground platforms where the convoys were assembled loaded onto a cattle truck, which formed part of Convoglio n.05 for Auschwitz. The 88-year-old Ernesto Reinach died en route. Mari Reinach De Benedetti, Ugo de Benedetti and 15-year-old Pietro de Benedetti arrived at Auschwitz on 11 December 1943. They were most probably gassed immediately on arrival. Piero’s brother Giancarlo was not with the family, he had been receiving treatment at a medical institution and was not with the family when they left Milan. In the end with the help of family friends and some benevolent Italians , he was eventually smuggled across the border into Switzerland and safety.

At the far end of via Togni at number 29 is a memorial for the Reinach’s neighbour Eduardo Orefice.

Born in Verona in March 1867. Edoardo married Olga Rava and they had three children Elda, Ida and Adolfo. The family moved to Milan, where Edoardo was the owner of a Private Bank, Orefice Fratelli in Via Victor Hugo. After the Racial Laws in 1938, Edoardo was forced to give up banking, when a special decree of 19 October 1938, revoked his licence to operate on Milan’s Borsa. He withdrew to the small town of Gazzada outside Varese, presumably in the hope that he could live his life peacefully there. Other members of the family, emigrated to Switzerland, but Edoardo and Olga stayed on in Gazzada. After the German occupation, he must have decided to go (without Olga who may have been too ill to travel or already deceased) . Edoardo never made it, he was betrayed and arrested somewhere near the frontier on 7 December 1943. , he was sent to San Vittore and was put on the train which left Binario 21 on 30 January 1944 for Auschwitz- where he was murdered on arrival. In 1946, further details of Edoardo’s betrayal came to light during the trail at the Court of Assizes in Novara of Antonia Vincenti Rosini and Umberto Mazzi. Both were charged under Article 58 of the Italian Penal code of having collaborated with the enemy to the detriment of Jewish Italian citizens for personal gain. While he was living in Gazzada, Edoardo had been introduced to Rosini who had offered to find a guide to get him across the border into Switzerland. The guide was an associate of Rosini’s , Umberto Mazzi. Edoardo agreed to pay 5,000 Lire to the people smugglers, to be delivered when it was confirmed he was safe. On 6 December, he left with Mazzi for the border. Rosini subsequently sent a note to his family that he had made it there safely to obtain payment of the 5,000 Lire. It was, therefore, an unpleasant surprise when he was subsequently spotted under arrest at Varese station and on his way to back Milan. Meanwhile Rosini was also implicated in the arrest of . Goldschmied and Jole Camerino Goldschmied. The Goldschmieds were at the time sheltering in Varese with the Albrighi family, they had heard the ( false ) news of Edoardo’s successful crossing into Switzerland and asked to be put in contact with Rosini. They agreed to pay Rosini , 20,000 Lire each to be taken across the border. This time Rosini demanded the money up front. The Goldschmieds were captured at the border (again Umberto Mazzi seems to have been involved) and sent off to their fate. Again, Rosini lied that they had made it safely, another family the Cammeos were negotiating to use her services- but fortunately they were tipped off that she was probably an informer and decided to reject her offer. Meanwhile, Rosini was also negotiating with Carlo Bassi from Venice to get him and his mother to safety. They were entrusted to Mazzi to get them across the border , he betrayed them to soldiers who blocked the road and arrested them, The Bassis were robbed of cash , gold and valuables worth around 400,000 Lire. They were slightly more fortunate than the others in that they were released due to old age or infirmity. After the war both Rosini and Mazzi were indicted for their many crimes, while many Fascists were granted an amnesty .this did not apply where their crimes, as was alleged in Rosini and Mazzi’s cases, had been committed for financial gain. So strangely diehard anti-Semites got an amnesty, while those acting only for the money did not. At their trial in Novara , damning evidence was presented. On 9 July 1946, both Rosini and Mazzi were sentenced to 15 years imprisonment. Rosini’s lawyers continued for years to argue for a reduced sentence and clemency on the basis that she had protected other Jewish refugees. Their requests rejected and she served a prison sentence until 1953, when she was released in a general amnesty. Maybe, she was not an anti-Semite, she certainly seems to have been an extremely cynical con woman, who manipulated the frail and desperate Orefice and the Goldschmieds out of large sums of money and either her or both her and Mazzi’s actions cost them their lives.

At the end of Togni , we come to via San Vittore turning right you walk past the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia and keeping walking, for about twenty metres before turning left into via Degli Olivetani where we find the monument for Ottaviano Pieraccini. The building is now a hotel, but looks like it was once an apartment building.

Ottaviano Pieraccini was born the third of five children He graduated in jurisprudence and transferred to Milan to practise as a lawyer. Ottaviano had inherited a certain moral intransigence from his father’s family (both his father Arnaldo and uncle Gaetano were on the register of Casellario Politico Centrale as socialists ) so Ottaviano became a natural opponent of the dictatorship. In 1942, he was along with Roberto Veratti, Lucio Luzzatto, Corrado Bonfantini e Lelio Basso, one of the original promoters of the socialist Movimento di Unità Proletaria. After the armistice Veratti who was a wanted man by the Nazi-Fascists, was unable to access the required medical treatment and died of septicaemia. Pieraccini took over his responsibilities. Following the 1 March 1944 General Strike, a tipoff led to the whole leadership of the MUP being arrested.

On 10 March, Pieraccini as imprisoned at San Vittore, transferred to Fossoli and on 7 August 1944 arrived at Mauthausen He was transferred to Gusen on 13 August 1944, and sent back to Mauthausen to the notorious infirmary” where he died on 30 March 1945.

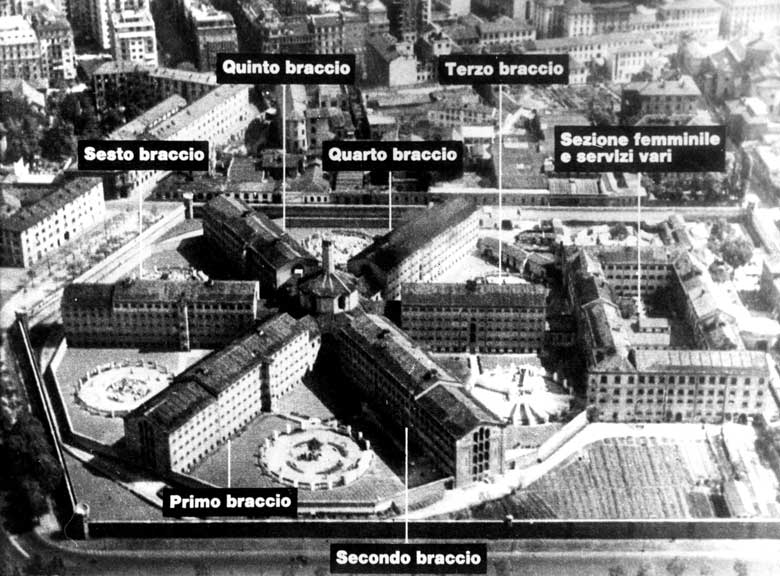

All these stories lead through San Vittore Prison, so it is appropriate that we get there in the end. I think you need an aerial view to get the full impression. Certainty flying a helicopter or a drone over an Italian prison is not recommended , so we have to make do with an old aerial photo, Bear in mind, it is still a working prison , so you cannot go in and extensive loitering outside is probably not recommended.

The construction of the new prison for Milan was decided after the Italian unification, in 1861 together with other infrastructure improvement works in Milan Until then, prisoners were detained in several other structures not designed as prisons, including the former Sant'Antonio Abate convent, in the Courthouse and in the former San Vittore convent. For the construction of the new prison the government acquired land on what was then the sparsely populated outskirts of the city. The building, designed by the engineer Francesco Lucca, takes inspiration from the 18th century Panopticon, with 6 wings radiating of the central tower with three floors each. The perimeter walls were originally built in medieval style, but have been rebuilt to modern standards for security reasons, The new prison opened on 7 July 1879 with places for 600 inmates.

During the German occupation he prison was partly subject to German jurisdiction, with the SS in control of one of three of the wings. On 10 August 1944 15 captured partisans held at the prison, handpicked by Theo Saevecke, head of the Gestapo in Milan, were publicly executed at Piazzale Loreto and left on display, as a reprisal for a partisan attack on a German military convoy. The prisons served as a transit camp for Jews arrested in northern Italy, who as we have seen were taken to Milano Centrale and Binario 21 , where they would be loaded into freight cars on a secret track underneath the station. The Germans took over blocks IV and VI to hold anti-fascists and political prisoners, block v was used as the Jewish wing. Bearing in mind that the whole prison had been built for six hundred , the Germans now crammed over 1300 prisoners into their wings. Cells which were designed for three people now held ten in conditions of absolute squalor, the fetid suffocating air carting the screams of the detainees . From September 1943 to January 1944, the German wing was nominally under the command of SS Hauptscharfuhrer Leander Klimsa , later replaced by SS Hauptscharfuhrer Helmet Klemm- but the real power was the brutal SS Rottenfuhrer Franz Staltmayer . known as La Belva “ The beast” .Staltmayer was a psychopath who roamed the German wings, with a German Shepherd dog and a whip. He casually doled out brutal beatings with his giant hands and oversized feet, occasionally he set the dog on inmates.

Fortunately among the brutality of the German guards and the indifference of most of the Italian ones, two Italian guards stood out for doing the right thing and are commemorated by two stones outside the prison for Sebastiano Pieri and Andrea Schivo. For the time being ( August 2023) the front of the prison is obscured by construction works for the new Blue Metro line( but the stones are visible) When the metro is finished you should be able to get a better view of the prison.

Sebastiano Pieri was born at Vasanello in April 1898. On 16 September 1923 he enrolled in the corpo delle guardie giudiziarie and transferred to Milan and San Vittore. Sebastiano Pieri was a well-regarded prison guard and in September 1938 he was promoted to “guardia scelta” and awarded a silver medal for his services. After 8 September 1943 and the German occupation his wing of San Vittore came under the control of the SS. Sebastiano worked in the infirmary and possibly what he witnessed there led to him assisting the detainees. Possibly he was on duty in the infirmary, when they bought in don Achille Bolis, a 70 year old Priest who had been violently tortured at the SS _HQ of the Albergo Regina and then on his arrival at San Vittore , by two Italians Manlio Melli and Dante Colombo of the UPI ( the political investigation office ) of the GNR, Don Achille died in the prison infirmary The Sipo SD issued a communique attributing the death of don Bolis to a pulmonary aneurism His body was claimed by Cardinal Ildefonso Schuster but nobody was permitted to see his remains, . All the religious leadership of Milan turned up for his funeral.

Luigi Ceraso, another ex -prison guard who had been deported for helping the detainees and who survived wrote in an 1963 article in Fu massacrato dalle SS di Saevecke Don Bolis

“ he was bought into a cell almost in front of mine, on the VI wing. I saw him come in peeping through the spy hole in my cell. He was accompanied by officials from the SS and Italian Fascists. He was pouring with bold and unable to stay on his feet. The same night, Don Bolis died… a nurse at San Vittore , who was successively deported to Germany, a certain Pieri, told me “ don Bolis was murdered”

After witnessing that Sebastiano offered to help the detainees stay in contact with their family outside the prison, smuggling our message concealed in his prison service cap- He helped until he was discovered On 17 March 1944 he was arrested and locked up in his own prison .On 27 April 1944 he was transported to Fossoli and on 21 June 1944, deported to Mauthausen. He died at Gusen on 19 January 1945.

Andrea Schivo was born on 17 July 1895 in Villanova d’Albenga ( Savona). He fought for Italy in the First World War on the Piave Front and was wounded. Because of his war service, after the war he was a Prison Guard at Imperia, then transferred to Milan to the San Vittore prison. After 8 September he was assigned to the wing controlled directly by the SS. To the best of his abilities Andrea tried to procure extra food for the Jewish detainees and to pass messages between them and their families. This was a very dangerous activity in a prison controlled by the SS. In the end Andrea was caught by an error, the SS guards found a piece of chicken bone in the Jewish wing – where such food would never have been given out. At the time, the Cardosi family – Clara Pirani Cardosi, her non-Jewish husband and their three daughters, including Guiliana (b. 1926) – were living in Gallarate, near Varese. Clara was arrested in May 1944 by the Varese police, whose efficiency in arresting Jews included ignoring the Salò Republic decisions concerning those from mixed families. She was taken to San Vittore prison, where she was held for a month, before being transferred to the Fossoli Di Carpi transit camp and then on to Auschwitz. While she was at San Vittore, Andrea Schivo helped pass letters between Clara and her family. Schivo also brought Clara packages of food and clothes prepared for her by her family. All these actions had to take place in complete secret, as the prison was frequented by Germans known for their cruelty and unwavering devotion to Nazi ideology. The letters from Clara were written on tiny pieces of paper and folded extremely small, in order that Schivo could bring them out without arousing suspicion amongst the Germans. In one of them, Clara warned her family to be careful, and asked them not to use Schivo's generosity too much in helping them, because security was being tightened and Schivo was placing himself at enormous risk. Nevertheless, the guard continued to bring her packages and letters, and never asked for any personal compensation. Immediately after Clara's transfer to Fossoli Di Carpi, Schivo was arrested for helping Jews. and locked up in the same prison where he worked. On 17 August he was transferred to the transit camp at Bolzano and from there to Flossenbürg where he died on 29 January 1945. The letters written by Clara to her family while at San Vittore appear in a book published by the Cardosi family. They testify to the help Schivo provided them during her period of incarceration. The book presents the eager collaboration of many Italians in the Nazi death machine, as well as those directly responsible for Clara's arrest and what became of them at the end of the war. The book also praises the heroic actions of those who refused to collaborate with the Germans, choosing instead the moral path of helping those in need. The Milan Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation investigated the events at San Vittore, and revealed that Schivo was indeed arrested and imprisoned at the jail before being transferred to Flossenbürg. A June 1945 letter signed by 19 prison guards state that Schivo was arrested as a direct result of helping provide food to a Jewish family. Schivo's niece, Carla Arrigoni Sala was a young girl during the war years. She testified that she had heard that a Jewish family was imprisoned at San Vittore, and that their young children cried all day long. One day Carla saw Schivo's wife crying while she cooked chicken for her husband to bring to the family. Carla suspects this was the dish that led to Schivo's arrest; the Germans found chicken bones and tortured an elderly member of the Jewish family until he revealed that Schivo was the one that had brought them the food. On 13 December 2006, Andrea Schivo was recognised as one of the ”Righteous Among Nations” by Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. The following 21 September, he was posthumously awarded the Medaglia d’Oro al Merto civile alla Memoria , by the President of the Italian Republic Giorgio Napolitano. The Italian Prison service renamed their Training School in his memory and a primary school in Villanova d’Albenga was named after him. It may sometimes take the Italians a while to getting round to doing the right thing, but they do in the end.

Leaving behind the prison , we emerge on the viale Papiniano and turn left to head towards Porto Genova , about 600 to 700 metres further south we can turn left into via Ausonio where at via number 20 is a memorial for Sebastiano Cappello.

Sebastiano was born in Sortino Sicily in May 1922, his family moved to Catania and in December 1939 to Milan, Sebastiano, worked as a carpenter and apparently also served as a volunteer with the Italian Navy the Regia Marina. The motives for his arrest remain a mystery ,he is apparently not recognised as a former partisan, However in 1943 the RSI began to draft men for their armed forces Originally the Salo regime tried to call up the men born in 1923 and 1925. Such was the poor response rate that in February 1944, the extended the call up to the class of 1922 and then to earlier years. The death penalty was introduced for draft evaders and deserters. The Germans fund it more useful to use them as forced labour. Possibly Sebastiano was detained for evading the draft, Whatever the reason for his arrest , if indeed there was any reason on 5 October 1944 he was deported to Dachau, then to Neuengamme; and its satellite camp Meppen-Versen in Lower saxony Here the prisoners were worked to death constructing the Friesenwall, fortifications designed to protect the -northern coast of Germany from Allied landings. . His exact place and date of death are unknown.

Doubling back a short way from via Ausonio , we reach the memorial for the Valabrega family at via Daniele Crespi 15.

Emanuele Valabrega and his wife Ida Cases and children Alma, Aldo, Bruno and Alberto, lived at corso Genova 16. The children attended the liceo Classico Manzoni. Emanuele died in a train accident in 1917 at Arquata Scrivia. Presumably after that the family were forced to move to via Daniele Crespi , Bruno married in 1930 and moved to via Strigelli 4 ( his deportation is separately commemorated there ) . Ida, Alma, Aldo and Alberto were arrested on 19 February 1944 and after San Vittore and were deported from Fossoli to Auschwitz on 5 April 1944. Their date of death is not known.

Returning to via Ausonio , we head straight down until we get to the junction with via Edmondo de Amicis, where at number 45 are the memorials to Michelangelo Boehm and Margherita Luzzato Boehm.

Born in Treviso in 1867, Michelangelo Boehm graduated in engineering from the Polytechnic of Milan. He married Margherita Luzzato, and they had three children. Michelangelo Boehm had assisted the Italian War effort in World War with gas supplies. In 1928 he was appointed a lecturer at his alma mater the Polytechnic. Boehm was nominated as the Italian Vice-president of the International Gas Union in 1932. At the 2nd Conference of the IGU in Zurich in 1932, he presented a paper on “The use of electricity in the manufacture of Town Gas”. In 1935, he received one of Italy’s highest honours being appointed an Officer of the Crown of Italy. In 1938, Italy’s Racial Laws ended Boehm’s long and distinguished career . He was no longer able to teach at the polytechnic, his honours were removed.

He and Margherita retired to the Valssasina above Lecco, hoping they were too old for anybody to bother them. Meanwhile their children had fled to Switzerland.

In December 1943, the elderly couple decided it was time to go. Unfortunately the were arrested not far from the Swiss border at Tirano. They were both taken to Tirano prison, then to Como, then to San Vittore prison in Milan There, they were separated. Margherita was sent to the transit camp at Fossoli and Michelangelo being over 70 was released. He was rearrested in Milan on 29 January 1944 and the next day was sent to Binario 21 to join Convoglio N. 12 for Auschwitz. The train arrived at Auschwitz on 6 February 1944, he was probably gassed immediately on arrival. Margherita was held at Fossoli until February 4 when she too was sent to Auschwitz, being gassed on arrival on 26 February 1944.